This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

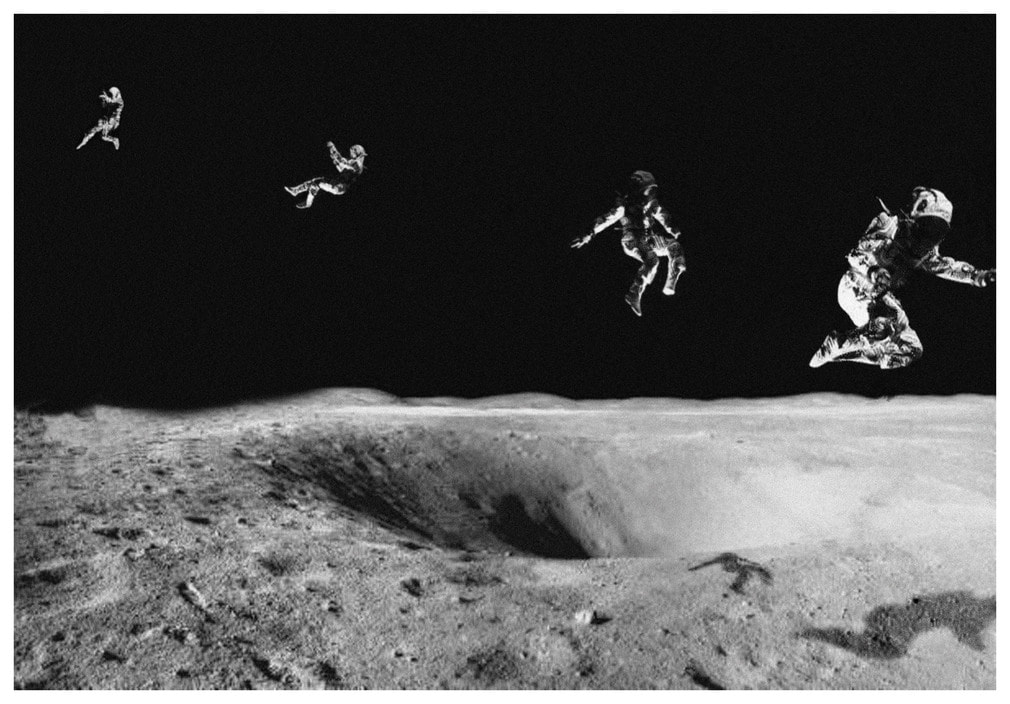

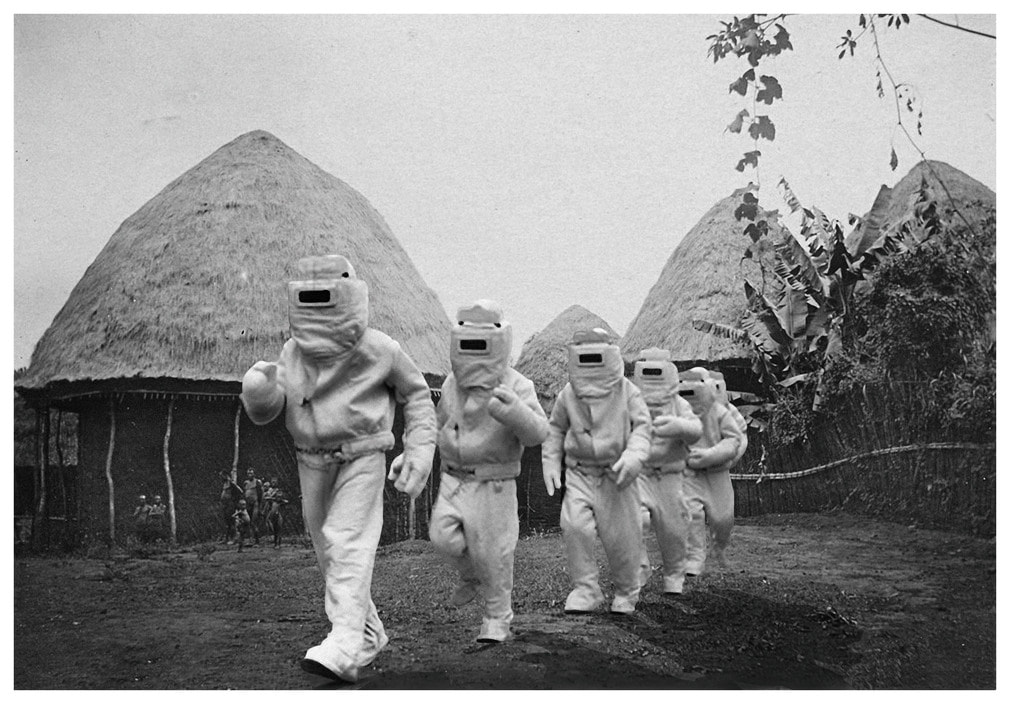

About the PhotographerCristina de Middel is a Spanish-Belgian photographer born in Alicante in 1975. After studying Fine Arts, she was a photojournalist working for Spanish local newspapers and NGOs like the Red Cross and Doctors without Borders for almost 10 years, covering crisis in Syria, Haiti and Bangladesh amongst others. In 2012 she produced "The Afronauts," a fictional series inspired by the real, yet unbelievable project that Zambia had to conquer the moon in the middle of the Space Race and the Cold War. The same year she self published a book of "The Afronauts" series, she was awarded with the Infinity Award for the best publication at the International Center of Photography in New York, the PhotoFolio Review Award at the Rencontres d´Arles, and she was a finalist of the prestigious Deutsche Börse Award for photography. The series "The Afronauts" has now been exhibited more than 50 times in museums and Institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum in NYC, The Hasselblad Foundation, the San Francisco MoMa, or the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Since 2012, de Middel has published more than 14 books and exhibited widely in the 5 continents. In 2017, she received the National Award for Photography in Spain and became part of Magnum Photos agency, which she has been the president of since 2022. Cristina is now based in Brazil and is continuously developing new projects. |

|

Truth in Photography: How is your work about truth in photography?

Cristina de Middel: I didn't have any mission for it. I didn't get interested in photography for the debate of truth or to question anything about truth. It was an aesthetical interest. I'm interested by the machine as well, and the doors it could open. I managed to become a photojournalist, but it was not easy. I stayed in the business working for local newspapers and for NGOs for ten years. And after eight years, I realized that I didn't want to be part of the machinery because this activism that I could recognize in the beginning of the power of image in making change and raising awareness was not that clear. There were plenty of things that you have to put in context and not believe blindly in that power of photography. So, I changed my dream, and the process was basically wanting to change the world with photography, and at some point realizing that in order to do that, I had to change photography first. If you can change photography, then maybe you can change the world.

I started in fine arts, but drawing and photography were too distant and too arrogant for the person that I am. I didn't want to talk to my audience from above, because in many cases, I felt inferior when looking at contemporary art. I don't like that feeling and I don't want to reproduce it. So, I went to the other extreme and that is trying to reach as many people as possible with my work in a plain language that was accessible for everyone, and that was photojournalism. But then I got disappointed with photojournalism. So, now I am too documentary to be an artist, and too artist to be a photojournalist.

TiP: How would you complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…?”

de Middel: Truth in photography is a tradition, something that became associated with photography at some point. And then it is a reproduction of that idea over and over again. And that has assimilates these two things. And I also think that all these debates about truth in photography could be very easily fixed if we changed truth for the word reality. Because many times I am asked, “Why don't you think photography's true?” There is a level of truth in photography, and it's the realistic level of the reproduction. You need reality to have photography. You don't need the truth to have photography. Truth is an idea. Reality belongs to the physical world, and photography belongs to the physical world, to start with, and then you can develop it into something else. So, reality in photography is a no brainer. Truth in photography is a philosophical question.

TiP: It is a philosophical question, because ultimately truth is a perception. It's a feeling about what we have and, in the case of photography, what we're looking at.

de Middel: And what you choose. Because in the end, it's a choice. You choose to believe in something, and you choose not to believe in something. For politics, for sports teams, you choose the reality you want to consume. And now the industry of truth and media is so well built, and so well produced, that you really can consume any version of reality in the shape of truth, the one that you choose. If you want to believe that we are going extinct, you have enough information to support that idea. If you want to believe that it's fake and we are doing just fine, and the world will continue, and we will be here forever no matter what we do to the planet, you also have as many articles to support that idea, and as many images to support that idea. So, there are enough versions of the yes and the no for you to just be able to choose what is your truth.

Cristina de Middel: I didn't have any mission for it. I didn't get interested in photography for the debate of truth or to question anything about truth. It was an aesthetical interest. I'm interested by the machine as well, and the doors it could open. I managed to become a photojournalist, but it was not easy. I stayed in the business working for local newspapers and for NGOs for ten years. And after eight years, I realized that I didn't want to be part of the machinery because this activism that I could recognize in the beginning of the power of image in making change and raising awareness was not that clear. There were plenty of things that you have to put in context and not believe blindly in that power of photography. So, I changed my dream, and the process was basically wanting to change the world with photography, and at some point realizing that in order to do that, I had to change photography first. If you can change photography, then maybe you can change the world.

I started in fine arts, but drawing and photography were too distant and too arrogant for the person that I am. I didn't want to talk to my audience from above, because in many cases, I felt inferior when looking at contemporary art. I don't like that feeling and I don't want to reproduce it. So, I went to the other extreme and that is trying to reach as many people as possible with my work in a plain language that was accessible for everyone, and that was photojournalism. But then I got disappointed with photojournalism. So, now I am too documentary to be an artist, and too artist to be a photojournalist.

TiP: How would you complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…?”

de Middel: Truth in photography is a tradition, something that became associated with photography at some point. And then it is a reproduction of that idea over and over again. And that has assimilates these two things. And I also think that all these debates about truth in photography could be very easily fixed if we changed truth for the word reality. Because many times I am asked, “Why don't you think photography's true?” There is a level of truth in photography, and it's the realistic level of the reproduction. You need reality to have photography. You don't need the truth to have photography. Truth is an idea. Reality belongs to the physical world, and photography belongs to the physical world, to start with, and then you can develop it into something else. So, reality in photography is a no brainer. Truth in photography is a philosophical question.

TiP: It is a philosophical question, because ultimately truth is a perception. It's a feeling about what we have and, in the case of photography, what we're looking at.

de Middel: And what you choose. Because in the end, it's a choice. You choose to believe in something, and you choose not to believe in something. For politics, for sports teams, you choose the reality you want to consume. And now the industry of truth and media is so well built, and so well produced, that you really can consume any version of reality in the shape of truth, the one that you choose. If you want to believe that we are going extinct, you have enough information to support that idea. If you want to believe that it's fake and we are doing just fine, and the world will continue, and we will be here forever no matter what we do to the planet, you also have as many articles to support that idea, and as many images to support that idea. So, there are enough versions of the yes and the no for you to just be able to choose what is your truth.

TiP: Looking at your work and your transition between photojournalism and what you're doing now, which doesn't really have an exact descriptor, as someone who writes nonfiction, but also writes fiction, I think that sometimes there’s more truth in fiction than there is truth in the reality that we see.

de Middel: It is like that. It's not that I have invented dynamic storytelling or anything like that. The mix between truth and reality has been there since the first books that were written, and we just accepted it. We look at the Bible, and there's probably some documentary in it, and there's probably some fiction as well. If you want to understand Russia at a certain period of history, Dostoyevsky is probably one of the best ways to understand what Russia looked like, and it's pure fiction. Because we live in such a scientific era, where scientific proof is what brings truth and validates something that exists, we tend to associate truth with something that gives value to things when it's not necessarily like that, when you're speaking about storytelling. We're not talking about some scientific experiment; we're explaining the world with language. And photography for me is ultimately a language. Truth is not necessarily a good thing to have in storytelling. If we want something really true, let's just make a list or tell what is going on in Ukraine minute after minute saying how many bombs are falling, in which place with the coordinates, with the exact time when they arrive, where they hit the target, how many people died, and who pushed the button, and just present the data. That's the most truthful thing you can have of the war. You will probably not even understand what is going on. So, truth is not good for storytelling. It's just a part that is important but not necessarily good. And I wish people understood that.

If you look at yourself, when you change your mind after reading an article, what happens in your brain? You think that a politician is good, and then you read an article that explains why he's not good and all the terrible things he's done. Then, in your brain, you change your mind. What is happening there is that your truth is moving to a different object. You choose, in a way, to believe in something else. And that, for me, is the plain proof, that when you link it to photography, or any type of information that you share with us, ultimately, if you do things well, you choose your truth. And that is for me the parameters in which we need to develop as people, as humans in society, and forget about truth, it's the coordinates. You will want to position yourself in the truth scheme of things, but you can move. It's not something absolute that is there. It's somewhere where you decide to move.

TiP: It's a process of learning. It's a process of perception. And then there's also the factor of time. Because over time, our perceptions change.

de Middel: But imagine what we're talking about then. We’re talking about truth, which is a philosophical question and debate. How would photography, which is such a limited tool, be able to solve that philosophical problem? Many times, I am asked, “What about truth?” There's been centuries of centuries of debate with very smart people trying to figure out what the truth is. I'm not going to fix that problem, or to find a solution, or find the ultimate definition, or carry all the responsibility of truth as a photographer. It's a debate we can have here, a constructive debate, but we’re not going to find a solution. It's not here. It's not in photography, where we find the answer to that question.

de Middel: It is like that. It's not that I have invented dynamic storytelling or anything like that. The mix between truth and reality has been there since the first books that were written, and we just accepted it. We look at the Bible, and there's probably some documentary in it, and there's probably some fiction as well. If you want to understand Russia at a certain period of history, Dostoyevsky is probably one of the best ways to understand what Russia looked like, and it's pure fiction. Because we live in such a scientific era, where scientific proof is what brings truth and validates something that exists, we tend to associate truth with something that gives value to things when it's not necessarily like that, when you're speaking about storytelling. We're not talking about some scientific experiment; we're explaining the world with language. And photography for me is ultimately a language. Truth is not necessarily a good thing to have in storytelling. If we want something really true, let's just make a list or tell what is going on in Ukraine minute after minute saying how many bombs are falling, in which place with the coordinates, with the exact time when they arrive, where they hit the target, how many people died, and who pushed the button, and just present the data. That's the most truthful thing you can have of the war. You will probably not even understand what is going on. So, truth is not good for storytelling. It's just a part that is important but not necessarily good. And I wish people understood that.

If you look at yourself, when you change your mind after reading an article, what happens in your brain? You think that a politician is good, and then you read an article that explains why he's not good and all the terrible things he's done. Then, in your brain, you change your mind. What is happening there is that your truth is moving to a different object. You choose, in a way, to believe in something else. And that, for me, is the plain proof, that when you link it to photography, or any type of information that you share with us, ultimately, if you do things well, you choose your truth. And that is for me the parameters in which we need to develop as people, as humans in society, and forget about truth, it's the coordinates. You will want to position yourself in the truth scheme of things, but you can move. It's not something absolute that is there. It's somewhere where you decide to move.

TiP: It's a process of learning. It's a process of perception. And then there's also the factor of time. Because over time, our perceptions change.

de Middel: But imagine what we're talking about then. We’re talking about truth, which is a philosophical question and debate. How would photography, which is such a limited tool, be able to solve that philosophical problem? Many times, I am asked, “What about truth?” There's been centuries of centuries of debate with very smart people trying to figure out what the truth is. I'm not going to fix that problem, or to find a solution, or find the ultimate definition, or carry all the responsibility of truth as a photographer. It's a debate we can have here, a constructive debate, but we’re not going to find a solution. It's not here. It's not in photography, where we find the answer to that question.

TiP: Perhaps you could talk a little bit about some specifics in your own work and highlights. How have you made this transition from photojournalism to more creative work, what have you focused on, and why?

de Middel: I think it came probably with a personal crisis. I was in Spain, and I was working at this local newspaper and there were lots and lots and lots of corruption cases. My routine was to go to the police station and wait out there for hours and hours and hours to take a picture of some politician. It became very boring, very frustrating. And also seeing how the media were reporting on all these things, I didn't agree. I started trying other things and finding B-side versions of reality that could keep me stimulated. And at some point, I don't know why, I started doing things the other way around and seeing what happens. For example, I started collecting spam emails instead of putting them in the trash. I had a very large collection of spam emails. We’re talking 2009. And reading these spam emails with care, as if you were reading a real story, and putting it in context and understanding that it's probably someone in West Africa in an Internet cafe writing the story that is very well designed as a trap for the Western guilt that we have towards Africa and terrorism. It presents a story and a version of reality that saves your soul, and also your bank account. You can help poor people and also get rich by helping poor people, which is the perfect trap and reveals a very deep understanding of how guilty we feel towards the countries that don’t have something better. So, I find it very smart in a way. I started reading all these spam emails and decided to do a robotic portrait of these people as if they really existed. Trying to imagine the scene that they describe. If it was a Russian widow, then it's a blond woman with a typical Russian hairstyle dressed in black in a torn-up palace that looks Russian. I went about building these scenes, finding actors, and taking the portrait that illustrates the spam. And to my surprise, I was lucky because I could do an exhibition of these works in Madrid. It was my first exhibition as a non-documentary photographer. And most of the people that came to see the exhibition, partly because I had a documentary background, but also because of the images, they thought it was real. They thought I had found these people, they had agreed to be photographed, and they agreed to be presented to the rest of the world like that. And for me, I learned the different reactions you have with the same story, if it is with or without an image that certifies its veracity. That just opened a playground for me because a spam email you don't even read it. You know it's a spam. You think it's a lie. But if it comes with a portrait of that person, then you start doubting to a level that even my boss at the newspaper, who came to the opening, he asked me, “Cristina, this is amazing. How did you gain access? How did they agree to be photographed?” And I was like, “Come on, these pictures are in Togo, in Nigeria. You know I have not been to these places. I didn't have holidays. You didn't give me any holidays the whole year.” But for him, the fact that the pictures existed, certified the existence of that story. That was 2009. I started rolling up my sleeves and I said, “Okay, this is what I want to say. This is what I want to talk about.” And then came The Afronauts.

de Middel: I think it came probably with a personal crisis. I was in Spain, and I was working at this local newspaper and there were lots and lots and lots of corruption cases. My routine was to go to the police station and wait out there for hours and hours and hours to take a picture of some politician. It became very boring, very frustrating. And also seeing how the media were reporting on all these things, I didn't agree. I started trying other things and finding B-side versions of reality that could keep me stimulated. And at some point, I don't know why, I started doing things the other way around and seeing what happens. For example, I started collecting spam emails instead of putting them in the trash. I had a very large collection of spam emails. We’re talking 2009. And reading these spam emails with care, as if you were reading a real story, and putting it in context and understanding that it's probably someone in West Africa in an Internet cafe writing the story that is very well designed as a trap for the Western guilt that we have towards Africa and terrorism. It presents a story and a version of reality that saves your soul, and also your bank account. You can help poor people and also get rich by helping poor people, which is the perfect trap and reveals a very deep understanding of how guilty we feel towards the countries that don’t have something better. So, I find it very smart in a way. I started reading all these spam emails and decided to do a robotic portrait of these people as if they really existed. Trying to imagine the scene that they describe. If it was a Russian widow, then it's a blond woman with a typical Russian hairstyle dressed in black in a torn-up palace that looks Russian. I went about building these scenes, finding actors, and taking the portrait that illustrates the spam. And to my surprise, I was lucky because I could do an exhibition of these works in Madrid. It was my first exhibition as a non-documentary photographer. And most of the people that came to see the exhibition, partly because I had a documentary background, but also because of the images, they thought it was real. They thought I had found these people, they had agreed to be photographed, and they agreed to be presented to the rest of the world like that. And for me, I learned the different reactions you have with the same story, if it is with or without an image that certifies its veracity. That just opened a playground for me because a spam email you don't even read it. You know it's a spam. You think it's a lie. But if it comes with a portrait of that person, then you start doubting to a level that even my boss at the newspaper, who came to the opening, he asked me, “Cristina, this is amazing. How did you gain access? How did they agree to be photographed?” And I was like, “Come on, these pictures are in Togo, in Nigeria. You know I have not been to these places. I didn't have holidays. You didn't give me any holidays the whole year.” But for him, the fact that the pictures existed, certified the existence of that story. That was 2009. I started rolling up my sleeves and I said, “Okay, this is what I want to say. This is what I want to talk about.” And then came The Afronauts.

TiP: The Afronauts series is really amazing. It's a faux reality that you're imagining, and it's clear, but it's very evolved.

de Middel: I am imagining something that really happened. I became sort of obsessed with, is it possible to make images of things that do not exist? Which is what I did with the previous series. I started looking for combinations of how to keep playing with that. I wanted to do the opposite, take pictures of things that do exist, but are unbelievable. Take a picture of something unbelievable, regardless of it being true or false. Then I started doing research on all these crazy experiments that were done in the US, back in the forties and fifties, and the beginning of those studies of the behavior and psychology, of the origins of psychology and behavior, where you would train pigeons to play ping pong and all the research that was done to see what the limits of obedience for soldiers were. I did that research because I wanted to take pictures of scientific experiments that were unbelievable. I landed on this website with the ten most crazy experiments in the history of humanity. The first one was the African Space Program, which is something that really happened in 1964. And there are very few documents about it, which is not important. What is, for me, important is how unbelievable this project is and why it is unbelievable is rooted in our prejudice towards a whole continent and our racism. We don't accept in our brains the idea of Africa going to space. So, the shock for me was so big that I thought it was a fake. I thought it was Joan Fontcuberta, who’s a specialist in these types of things, who had done something else and left the seed here and there. But it was true. And I thought, okay, there are no images of this. Let's make images. How do I imagine images? What I did actually is to document my own prejudice and my own stereotype of Africa, where I have never been, and space, I have never been to space, and just mix it together and create images that could, potentially, in our stereotyped mind and understanding of Africa fit perfectly our projection of it.

TiP: Joan Fontcuberta has a great sense of humor. I think another part of what we're talking about, in taking photographs that are hard to believe, and that’s the element of irony. But then there's the element of humor. In some sense, laughter is the realization of a truth we didn't realize was there. Why are we laughing? What makes an image funny? Is it just the content or is it something else? Is it the composition? Is it the framing?

de Middel: I think it can come from many, many, many places. Laughter, I think, is a reaction to surprise, to something unexpected. Humor and irony can also be the shield you build around yourself to address very serious problems. If you have trauma, you will make fun about that trauma because it's something that protects you against the seriousness of the trauma, and how difficult it is to swallow reality. The perfect makeup is irony and sense of humor. I do that as a person, myself. It's a very important tool in my life. For me, something makes me laugh when it's an unexpected combination of two ideas. Most of the time, it’s unexpected associations, something that at the same time reduces the seriousness of a situation. It's always bringing things back to something that you can manage, and it can be all levels of humor. It’s someone falling. In this first layer of humor, clown comedy, you are degrading the seriousness of being a human. Then you can become more intellectual, and you can degrade different aspects of someone and play with identity and play with so many aspects of what defines you. For me, this is the most difficult, but also the most enjoyable way of telling a story. When you manage to put humor or irony in there, I think it works very well. It's a Trojan horse strategy. When you want to say something harsh and you don't want to be aggressive, you just put on a smile and say, “Hey, you know, this is what I think.”

de Middel: I am imagining something that really happened. I became sort of obsessed with, is it possible to make images of things that do not exist? Which is what I did with the previous series. I started looking for combinations of how to keep playing with that. I wanted to do the opposite, take pictures of things that do exist, but are unbelievable. Take a picture of something unbelievable, regardless of it being true or false. Then I started doing research on all these crazy experiments that were done in the US, back in the forties and fifties, and the beginning of those studies of the behavior and psychology, of the origins of psychology and behavior, where you would train pigeons to play ping pong and all the research that was done to see what the limits of obedience for soldiers were. I did that research because I wanted to take pictures of scientific experiments that were unbelievable. I landed on this website with the ten most crazy experiments in the history of humanity. The first one was the African Space Program, which is something that really happened in 1964. And there are very few documents about it, which is not important. What is, for me, important is how unbelievable this project is and why it is unbelievable is rooted in our prejudice towards a whole continent and our racism. We don't accept in our brains the idea of Africa going to space. So, the shock for me was so big that I thought it was a fake. I thought it was Joan Fontcuberta, who’s a specialist in these types of things, who had done something else and left the seed here and there. But it was true. And I thought, okay, there are no images of this. Let's make images. How do I imagine images? What I did actually is to document my own prejudice and my own stereotype of Africa, where I have never been, and space, I have never been to space, and just mix it together and create images that could, potentially, in our stereotyped mind and understanding of Africa fit perfectly our projection of it.

TiP: Joan Fontcuberta has a great sense of humor. I think another part of what we're talking about, in taking photographs that are hard to believe, and that’s the element of irony. But then there's the element of humor. In some sense, laughter is the realization of a truth we didn't realize was there. Why are we laughing? What makes an image funny? Is it just the content or is it something else? Is it the composition? Is it the framing?

de Middel: I think it can come from many, many, many places. Laughter, I think, is a reaction to surprise, to something unexpected. Humor and irony can also be the shield you build around yourself to address very serious problems. If you have trauma, you will make fun about that trauma because it's something that protects you against the seriousness of the trauma, and how difficult it is to swallow reality. The perfect makeup is irony and sense of humor. I do that as a person, myself. It's a very important tool in my life. For me, something makes me laugh when it's an unexpected combination of two ideas. Most of the time, it’s unexpected associations, something that at the same time reduces the seriousness of a situation. It's always bringing things back to something that you can manage, and it can be all levels of humor. It’s someone falling. In this first layer of humor, clown comedy, you are degrading the seriousness of being a human. Then you can become more intellectual, and you can degrade different aspects of someone and play with identity and play with so many aspects of what defines you. For me, this is the most difficult, but also the most enjoyable way of telling a story. When you manage to put humor or irony in there, I think it works very well. It's a Trojan horse strategy. When you want to say something harsh and you don't want to be aggressive, you just put on a smile and say, “Hey, you know, this is what I think.”

TiP: What are you working on now?

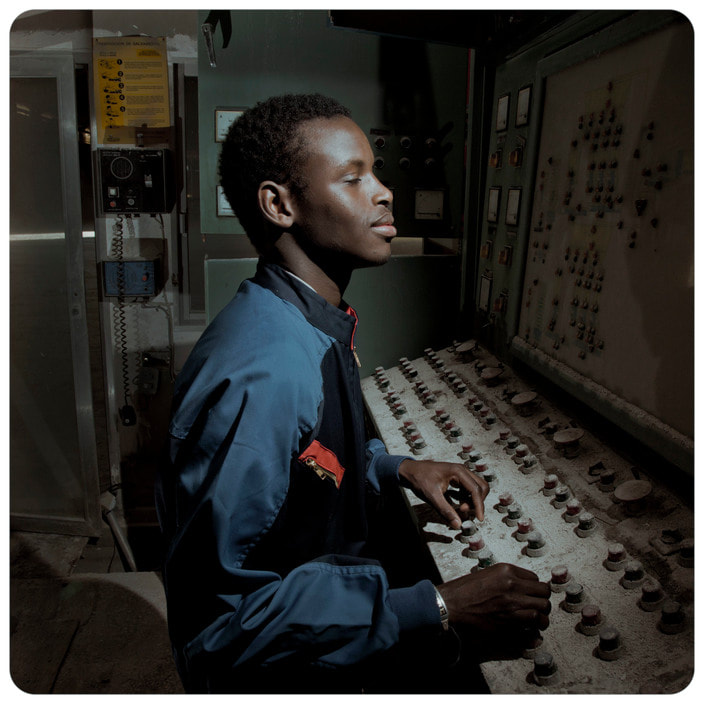

de Middel: I am finishing three projects. They are at different stages. I'm preparing the book for Gentlemen's Club, which is a project I've been doing around sex work, trying to present things from an uncommon angle, the angle of the client. I've been photographing the clients of prostitutes in ten different cities around the world, to bring light and provide information that the media never gives. Like what the clients look like. It's a project that is 99% documentary. There is 1% where I allow myself to go a little bit into fiction. But it's all real interviews with real people in real places. And the 1%, that person, that portrait that is not the real one is a sort of a hint to the movie, to Hollywood. I talk about the movie Pretty Woman. And it's a character, a pretty woman there, so there's a little bit of fiction.

I am also editing a book about immigration called Journey to the Center, and I try to shift the perception of migrants, again by the media, that is normally associated with criminality and people who are runaways or cowards. And I borrow the structure of an adventure book by Jules Verne, Journey to the Center of the Earth, to explain their journey from this heroic angle.

I am also editing the magazine that I'm doing with Lorenzo Meloni, who's a war photographer for Magnum. And we went to Afghanistan in January. I'm giving what we hope is a different angle on the traditional way of explaining Afghanistan.

de Middel: I am finishing three projects. They are at different stages. I'm preparing the book for Gentlemen's Club, which is a project I've been doing around sex work, trying to present things from an uncommon angle, the angle of the client. I've been photographing the clients of prostitutes in ten different cities around the world, to bring light and provide information that the media never gives. Like what the clients look like. It's a project that is 99% documentary. There is 1% where I allow myself to go a little bit into fiction. But it's all real interviews with real people in real places. And the 1%, that person, that portrait that is not the real one is a sort of a hint to the movie, to Hollywood. I talk about the movie Pretty Woman. And it's a character, a pretty woman there, so there's a little bit of fiction.

I am also editing a book about immigration called Journey to the Center, and I try to shift the perception of migrants, again by the media, that is normally associated with criminality and people who are runaways or cowards. And I borrow the structure of an adventure book by Jules Verne, Journey to the Center of the Earth, to explain their journey from this heroic angle.

I am also editing the magazine that I'm doing with Lorenzo Meloni, who's a war photographer for Magnum. And we went to Afghanistan in January. I'm giving what we hope is a different angle on the traditional way of explaining Afghanistan.

Los Angeles, June 12, 2022. Edward Lewis, 50, investor, married.

After a very stressful working day in Los Angeles and breaking up with his girlfriend over the phone, Edward borrowed his lawyer’s car to take some fresh air and disconnect from the pressures of life, but he got lost and asked one of the girls on Hollywood Boulevard for directions. She was nice and very helpful, and he ended up inviting her to spend the night at his hotel with him. Her name was Vivian and there was very good chemistry between them, so he asked her to stay for the rest of the week in exchange for USD 3,000, which she accepted. He invested in her wardrobe so that she could accompany him to his business dinners, and after some days he started to develop feelings for her. He’d always been reluctant to show his emotions or succumb to a romantic relationship, but with this girl things felt different, and when the week was over, after some hesitation, he went looking for her again and took her from the streets forever by marrying her. © Cristina de Middel / Magnum Photos

TiP: In Gentlemen’s Club, did you focus on Thailand?

de Middel: I did. I went to Bangkok. I went to Mumbai, to the same neighborhood where Mary Ellen Mark worked. I went to Mexico to work with transsexuals. I was in Rio. I tried to go to all the cities that have a relationship with sex work, whether it is romantic, or historical, or real sex tourism as part of their economy. There are ten different cities: L.A., Amsterdam, Paris, Lagos, Kabul, Bombay, Bangkok, Rio, Mexico.

TiP: When making photographs like that, because obviously so much of what you're learning is through these interactions you're having with these people, and you're trying to get them to talk about interactions they have in the sex trade, how do you work? How do you do this?

de Middel: I decided I would ask the same questions to all the men. To add a layer of cultural differences between all of them, and try to have all the same objective data about them. And so basically, three or four questions are their age, their occupation, if they're married or not, if they're single, if they have girlfriend. Trying to find what defines them. And then, when was the first time they paid for sex and in which conditions? Many of them, especially in Latino and African countries, were brought there by someone from their family going to a brothel. In Latin America, in Mexico, especially, almost 100% of them, I can't remember the numbers exactly, were taken there by an uncle or their father to make sure they were straight. It's a proof of virility, in a way. And for others, it can be revenge because the wife is not interested in sex anymore or they had a fight and things like that. Then, how they decide that it's a good idea to go and pay for sex, how much they pay at the time, and what is the frequency they use this service now, because some of them just did it once. Others go every day. How much they pay now. Then I ask for a reflection of what they think about the business. If it should disappear. Sometimes, in Amsterdam for example, I asked them that now with the rights of women changing rapidly, if they would prefer their wife to be a client or a sex worker. And the answers are interesting

de Middel: I did. I went to Bangkok. I went to Mumbai, to the same neighborhood where Mary Ellen Mark worked. I went to Mexico to work with transsexuals. I was in Rio. I tried to go to all the cities that have a relationship with sex work, whether it is romantic, or historical, or real sex tourism as part of their economy. There are ten different cities: L.A., Amsterdam, Paris, Lagos, Kabul, Bombay, Bangkok, Rio, Mexico.

TiP: When making photographs like that, because obviously so much of what you're learning is through these interactions you're having with these people, and you're trying to get them to talk about interactions they have in the sex trade, how do you work? How do you do this?

de Middel: I decided I would ask the same questions to all the men. To add a layer of cultural differences between all of them, and try to have all the same objective data about them. And so basically, three or four questions are their age, their occupation, if they're married or not, if they're single, if they have girlfriend. Trying to find what defines them. And then, when was the first time they paid for sex and in which conditions? Many of them, especially in Latino and African countries, were brought there by someone from their family going to a brothel. In Latin America, in Mexico, especially, almost 100% of them, I can't remember the numbers exactly, were taken there by an uncle or their father to make sure they were straight. It's a proof of virility, in a way. And for others, it can be revenge because the wife is not interested in sex anymore or they had a fight and things like that. Then, how they decide that it's a good idea to go and pay for sex, how much they pay at the time, and what is the frequency they use this service now, because some of them just did it once. Others go every day. How much they pay now. Then I ask for a reflection of what they think about the business. If it should disappear. Sometimes, in Amsterdam for example, I asked them that now with the rights of women changing rapidly, if they would prefer their wife to be a client or a sex worker. And the answers are interesting

TiP: What are you trying to convey through the photographs?

de Middel: There is a sense of confession that I think is important. The light and the way that they pose for me, or that I ask them to pose, is normally something that makes them look at ease. It's in the bed trying to replicate the situation but inverted because in this case they are selling something to me and I am paying. It's an important part of the project, that I pay for that confession. Or I pay and then pay for the room because in these types of transactions, they are just like the prostitutes or sex workers who sell something that is theirs. There's a sort of degradation in that. They also do that. They also accept to be photographed in exchange of money. And they are very aware that they are selling something that is very private. This is an extra layer, and the prices that I have to pay for them are also changing and interesting. I tried to create pictures that were intimate, but that were at the same time true, that you could feel somehow the connection and the trust there was between these people and me, which was not always easy because some of them were clearly doing it for the money and they were not comfortable at all talking with me. Others, they were very fine.

TiP: Do you mind me asking how much you pay them?

de Middel: It depends. In Bangkok, it was somewhere around $5 to $10. In Cuba, it was $20, which is the equivalent of a monthly salary. In Paris, I had to pay much more. It was close to $100. In L.A., they couldn't be in the pictures because it's a crime to use the service of prostitutes. So, I photographed their cars. And it's an interesting way of understanding who is in the picture through the car, which is also very linked to L.A. and the way of life there. In Amsterdam, also, they didn't want to be photographed, so I took photographs of the rooms in the Red District, so I didn't have to pay. Well, I had to pay for the rental of the rooms.

de Middel: There is a sense of confession that I think is important. The light and the way that they pose for me, or that I ask them to pose, is normally something that makes them look at ease. It's in the bed trying to replicate the situation but inverted because in this case they are selling something to me and I am paying. It's an important part of the project, that I pay for that confession. Or I pay and then pay for the room because in these types of transactions, they are just like the prostitutes or sex workers who sell something that is theirs. There's a sort of degradation in that. They also do that. They also accept to be photographed in exchange of money. And they are very aware that they are selling something that is very private. This is an extra layer, and the prices that I have to pay for them are also changing and interesting. I tried to create pictures that were intimate, but that were at the same time true, that you could feel somehow the connection and the trust there was between these people and me, which was not always easy because some of them were clearly doing it for the money and they were not comfortable at all talking with me. Others, they were very fine.

TiP: Do you mind me asking how much you pay them?

de Middel: It depends. In Bangkok, it was somewhere around $5 to $10. In Cuba, it was $20, which is the equivalent of a monthly salary. In Paris, I had to pay much more. It was close to $100. In L.A., they couldn't be in the pictures because it's a crime to use the service of prostitutes. So, I photographed their cars. And it's an interesting way of understanding who is in the picture through the car, which is also very linked to L.A. and the way of life there. In Amsterdam, also, they didn't want to be photographed, so I took photographs of the rooms in the Red District, so I didn't have to pay. Well, I had to pay for the rental of the rooms.

Mexico City, Mexico, February 22, 2020. Norman, 44, salesman, divorced with a son.

Norman likes extremely feminine-looking partners, and he used to hang out in the gay area of Mexico City admiring the beauty of the transgender sex workers. One night he decided to pay for the most beautiful one, paying close to 1,500 MXN, and after that he became a regular client. He can’t talk openly about it because he comes from a Catholic family that would not understand his tastes, but he thinks that in general men paying for sex is an open secret. He says the secrecy of the whole thing is part of what excites him, and he’s happy to pay extra for the girl's discretion. For him the business of sex work covers an immediate physical need in the first instance, but there’s also an important part in being listened to without judgment and receiving advice from women who have a lot of life experience. © Cristina de Middel / Magnum Photos

TiP: Did any of the people you interviewed ever have any kind of moral or ethical awakening that what they were doing was morally wrong? And did they ever identify with the way in which these women were being victimized?

de Middel: Yes, there's many, many cases. I would say that almost half of them gave statements against prostitution and what it means for women to be sold like that, or to sell their bodies like that. In France, they were extremely elaborate about it. They did really elaborate their replies and justified very well why it makes sense. Sometimes arguing about the rights of women to sell their bodies and saying that prostitution is empowering women because they decide ultimately about everything. My mission there is not to judge. I really try to present information as neutrally as possible so people can decide, because there is a strong debate around it. But we don't have the information coming from the men. We don't understand why it exists. What is the drive? We need that information. And then when we have it, then maybe we can have a debate. I've had to interview men who literally waited outside of schools, waiting for young girls. And others who have the sexual fantasy of raping a woman and would rather pay for a prostitute to pretend she's being raped than to really rape a woman. And in L.A., most of the clients that I interviewed, I found in Sex Addicts Anonymous. So, they are people who are already in therapy.

TiP: In terms of focusing on Afghanistan, this is some of your newest work. What are you trying to do there?

de Middel: The work in Afghanistan makes sense in the context of a collaboration with Lorenzo Meloni. It was something we wanted to do within Magnum, because he represents one of the most traditional parts that define Magnum in war photography. It's part of how the founding origins, the founding drive of Magnum, was very much related to war photography and Capa. I maybe represent the most transgressive or open-minded approach to photography, questioning precisely what war photography is based on. We wanted to see as a team what we could do to explain and to illustrate one of the most photographed countries in the news. And lately that's been Afghanistan because it's been at war for 30 years. So we went there at a very precise time, right after the victory of the Taliban in January. And we decided to just complete the picture, because there's been thousands and thousands of images coming from Afghanistan. But you never really know what the country is like and its habits and what people eat, what people do for fun. You don't have all the information about the country. You know it's been at war, and it's been at war, and it's been at war, and war and war and war. But what is their typical dish? There was a lot of information missing in our idea of Afghanistan, and we just went there to complete it. And we are doing a magazine called The Kabuler, in dialogue with The New Yorker. And it will have all the sections that the magazine would have with sports, gastronomy, travel, cars, international news, local news. We really want to make a magazine with the advertising and everything.

de Middel: Yes, there's many, many cases. I would say that almost half of them gave statements against prostitution and what it means for women to be sold like that, or to sell their bodies like that. In France, they were extremely elaborate about it. They did really elaborate their replies and justified very well why it makes sense. Sometimes arguing about the rights of women to sell their bodies and saying that prostitution is empowering women because they decide ultimately about everything. My mission there is not to judge. I really try to present information as neutrally as possible so people can decide, because there is a strong debate around it. But we don't have the information coming from the men. We don't understand why it exists. What is the drive? We need that information. And then when we have it, then maybe we can have a debate. I've had to interview men who literally waited outside of schools, waiting for young girls. And others who have the sexual fantasy of raping a woman and would rather pay for a prostitute to pretend she's being raped than to really rape a woman. And in L.A., most of the clients that I interviewed, I found in Sex Addicts Anonymous. So, they are people who are already in therapy.

TiP: In terms of focusing on Afghanistan, this is some of your newest work. What are you trying to do there?

de Middel: The work in Afghanistan makes sense in the context of a collaboration with Lorenzo Meloni. It was something we wanted to do within Magnum, because he represents one of the most traditional parts that define Magnum in war photography. It's part of how the founding origins, the founding drive of Magnum, was very much related to war photography and Capa. I maybe represent the most transgressive or open-minded approach to photography, questioning precisely what war photography is based on. We wanted to see as a team what we could do to explain and to illustrate one of the most photographed countries in the news. And lately that's been Afghanistan because it's been at war for 30 years. So we went there at a very precise time, right after the victory of the Taliban in January. And we decided to just complete the picture, because there's been thousands and thousands of images coming from Afghanistan. But you never really know what the country is like and its habits and what people eat, what people do for fun. You don't have all the information about the country. You know it's been at war, and it's been at war, and it's been at war, and war and war and war. But what is their typical dish? There was a lot of information missing in our idea of Afghanistan, and we just went there to complete it. And we are doing a magazine called The Kabuler, in dialogue with The New Yorker. And it will have all the sections that the magazine would have with sports, gastronomy, travel, cars, international news, local news. We really want to make a magazine with the advertising and everything.

Kabul, Afghanistan, January 24, 2022. Abbas, 23, graphic design graduate, unemployed, in a relationship.

In 2020 Abbas decided it was time for him to lose his virginity and went to an area of Kabul called Chār Qala where he knew from a friend there were girls available. He paid 1,800 AFN for a 30 minute session which he enjoyed very much and found very relieving. Since then he’s been going to the same place once a month because it makes him feel really good. He says some of the girls he pays for do it for pleasure and others are forced to do it because they need the money. He prefers to see the girl enjoying herself even if he’s paying, because that also gives him a lot of pleasure. He says he only has sex with real love with his girlfriend, and he’s teaching her what he learns with the sex workers so that he can have both things – good sex and love. © Cristina de Middel / Magnum Photos

|

|

Delve deeper |