This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the ArtistErgin Çavuşoğlu (Bulgaria) studied at the National School of Fine Arts, Sofia, Marmara University (BA), Istanbul, Goldsmiths College (MA), London, and the University of Portsmouth (PhD). Çavuşoğlu co-represented Turkey at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003. He was shortlisted for the Beck’s Futures Prize in 2004 and for Artes Mundi 4 in 2010. Central to Çavuşoğlu’s artworks are concepts that explore ideas of place, space, liminality, mobility, and the conditions of cultural production, which he has been examining in classical, modern, and contemporary guises through video and sound installations, photography, anamorphic drawings, and sculptures. He has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in museums and galleries worldwide and participated in major biennials such as Manifesta 8 (2010), the British Art Show 6 (2005), the 8th Istanbul Biennial (2003) and the 3rd Berlin Biennial (2003). His works are represented in museum collections, including Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection, Frac Alsace, Pinakothek der Moderne, München, EMST, Athens, Istanbul Modern, The Ludwig Collection, and Sammlung Goetz, Munich, among others. Çavuşoğlu lives and works in London, where he is currently a Professor of Contemporary Art at Middlesex University. His work can be seen in the exhibition Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy, on view at the International Center of Photography from June 1 – September 11, 2023. |

|

The journey down the current of all those who were adrift (2022). A geodesic dome: Ø 500 cm x H296 cm, powder-coated steel tube, canvas with PVC membrane. Carved Bursa Uludağ Black marble Ø 300 cm, soil, video wall 218 x 124 cm, single channel (1920x1080) HD video, sound, lights. Cinematography Engin Aygun. © Ergin Çavuşoğlu

Truth in Photography: Talk about the work you're exhibiting at the International Center of Photography (ICP).

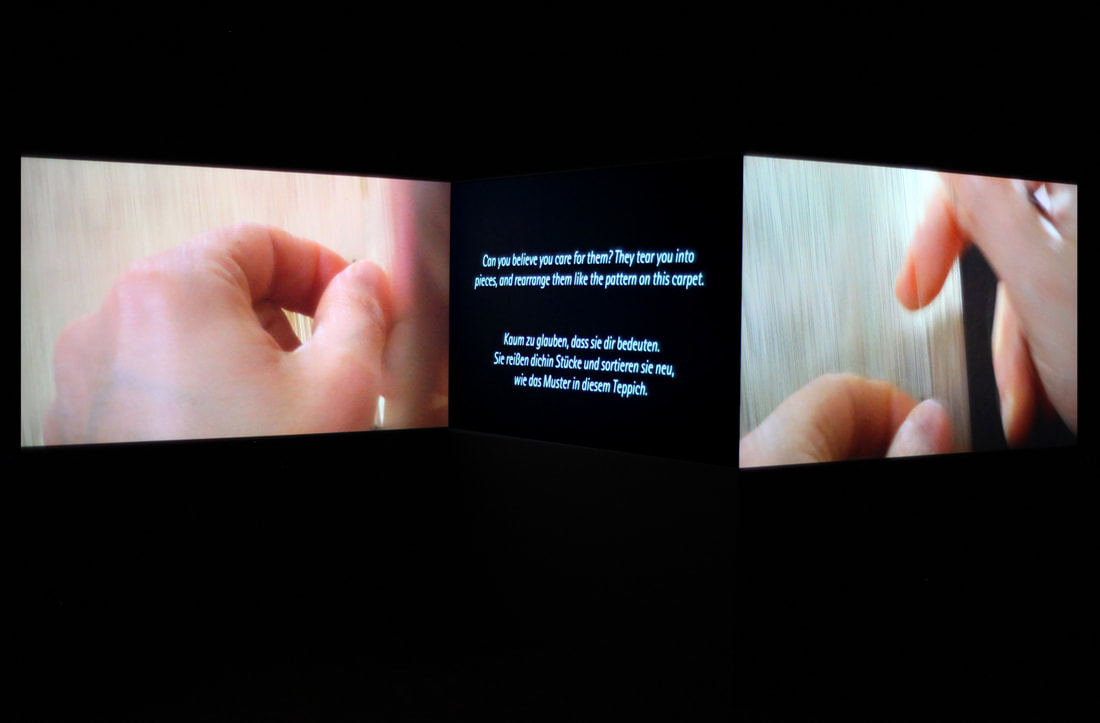

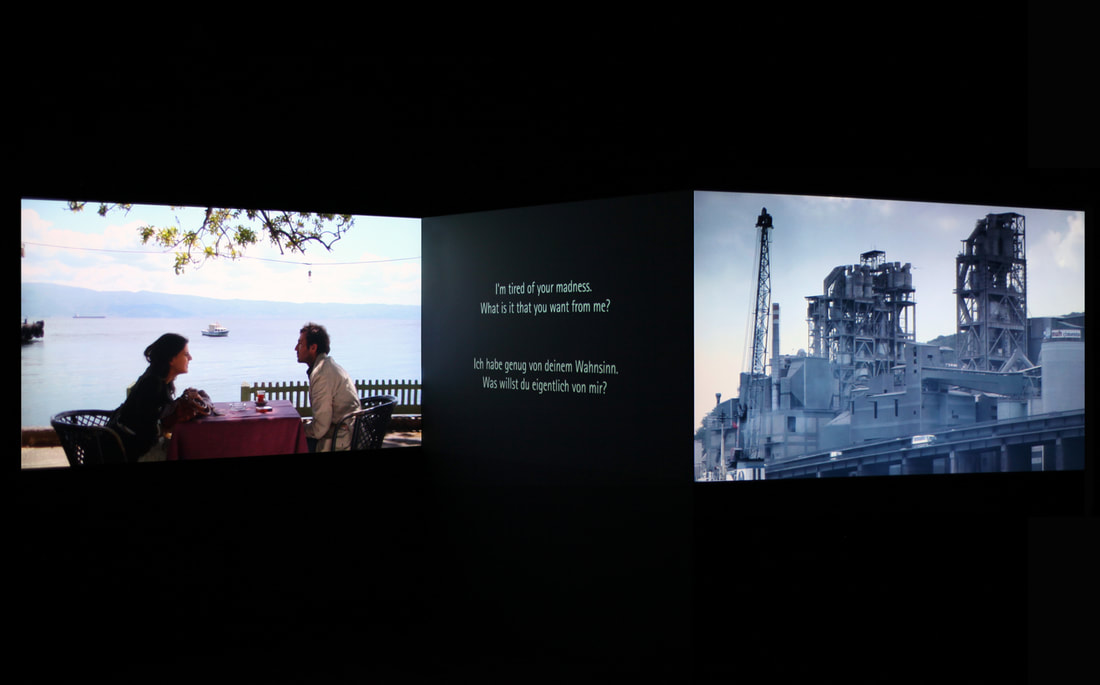

Ergin Çavuşoğlu: I will be exhibiting a three-channel video installation called Silent Glide from 2008. The work is based on a feature film titled Ephemeral Patterns that I wrote around 2005-2006, which was commissioned by the then UK Film Council acknowledging at the time the potential of artists making feature films. I spent three years developing the storyline and then scripting it with a New York-based writer and a long-time collaborator, Arnold Barkus. I wrote Silent Glide later as a spin-off of the feature film. It was shot in the same location where the feature film would have taken place, but the twists in the storyline and the starting point for the video installation are different. At the conceptual core of Silent Glide, there is a character that is based loosely on Leo Tolstoy's own image in his memoir called A Confession from 1882. It is about two characters who are both driven by their own moral values. One is an ambitious journalist based in Istanbul called Tulya, and Halil, the main character, is an academic researcher in oriental carpets working in the small coastal town Hereke, near Istanbul, once designated by the sultan for the production of the finest silk carpets and frequented by the likes of Queen Victoria and Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Ergin Çavuşoğlu: I will be exhibiting a three-channel video installation called Silent Glide from 2008. The work is based on a feature film titled Ephemeral Patterns that I wrote around 2005-2006, which was commissioned by the then UK Film Council acknowledging at the time the potential of artists making feature films. I spent three years developing the storyline and then scripting it with a New York-based writer and a long-time collaborator, Arnold Barkus. I wrote Silent Glide later as a spin-off of the feature film. It was shot in the same location where the feature film would have taken place, but the twists in the storyline and the starting point for the video installation are different. At the conceptual core of Silent Glide, there is a character that is based loosely on Leo Tolstoy's own image in his memoir called A Confession from 1882. It is about two characters who are both driven by their own moral values. One is an ambitious journalist based in Istanbul called Tulya, and Halil, the main character, is an academic researcher in oriental carpets working in the small coastal town Hereke, near Istanbul, once designated by the sultan for the production of the finest silk carpets and frequented by the likes of Queen Victoria and Kaiser Wilhelm II.

TiP: How do you differentiate between different media in your creative process?

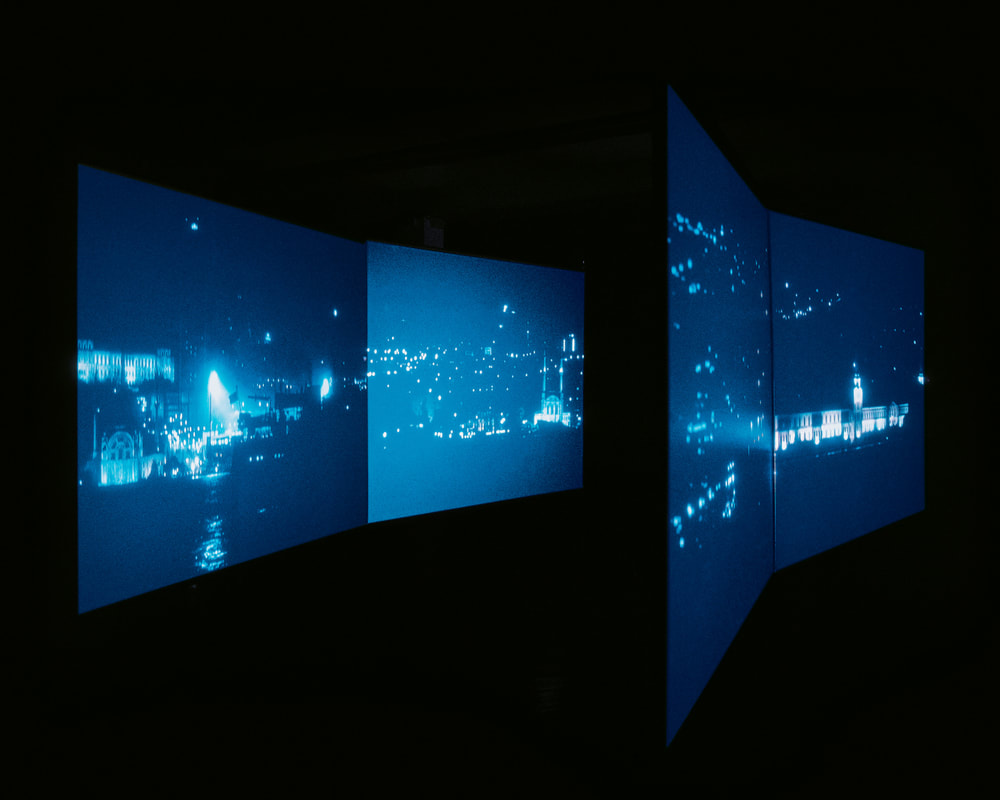

Çavuşoğlu: My trajectories in art have taken me from a very classical education, which I undertook in the early 1980s in Bulgaria during communist times, to modernist Bauhaus study in Istanbul, and then contemporary art in London. It was interesting transitioning through different media from painting, sculpture, and drawing to photography. In fact, I spent probably 15 to 18 years working predominantly in photography and then began exploring film. The reason for that was that the moving image or the sequence of stills in a timeline allowed me to tell stories from multiple perspectives. I found the medium a little bit more democratic in that sense. I was able to employ other abilities and interests in literature or in making; sculpting and painting, that I could then actually feature in the films. I kind of arrived at the moving image, rather than starting with it. Photography's been instrumental in allowing me a distance from the skill-based making processes. Of course, photography requires the employment of a range of specialist skills but obviously, it's a different and often more technical engagement. Moreover, it permeates conceptual thinking which is different from the internal discourses at play within more traditional art forms. In a way, photography allowed me to conceptualize and contextualize my thinking rather than advancing through making, because there is an element of playfulness which occurs when you work on a canvas or sculpt. However, nowadays my practice is much more diverse than if I go back and look at distinct periods in the past. Then I just worked with photography or only moving images. There was a prolonged period when I intentionally only filmed at night when spaces become liminal and are redefined. It was very important for me to dislocate places and devoid them of their everyday content and context. My current artworks are much less medium-specific and very much ideas driven, so it's a kind of Deleuze-an idea. He said things like an idea in film is not an idea in literature or in philosophy. It is interesting that distinguishing between different mediums allows you to express that concept or idea in its fullness. It is quite an important aspect of my thinking and practice.

Çavuşoğlu: My trajectories in art have taken me from a very classical education, which I undertook in the early 1980s in Bulgaria during communist times, to modernist Bauhaus study in Istanbul, and then contemporary art in London. It was interesting transitioning through different media from painting, sculpture, and drawing to photography. In fact, I spent probably 15 to 18 years working predominantly in photography and then began exploring film. The reason for that was that the moving image or the sequence of stills in a timeline allowed me to tell stories from multiple perspectives. I found the medium a little bit more democratic in that sense. I was able to employ other abilities and interests in literature or in making; sculpting and painting, that I could then actually feature in the films. I kind of arrived at the moving image, rather than starting with it. Photography's been instrumental in allowing me a distance from the skill-based making processes. Of course, photography requires the employment of a range of specialist skills but obviously, it's a different and often more technical engagement. Moreover, it permeates conceptual thinking which is different from the internal discourses at play within more traditional art forms. In a way, photography allowed me to conceptualize and contextualize my thinking rather than advancing through making, because there is an element of playfulness which occurs when you work on a canvas or sculpt. However, nowadays my practice is much more diverse than if I go back and look at distinct periods in the past. Then I just worked with photography or only moving images. There was a prolonged period when I intentionally only filmed at night when spaces become liminal and are redefined. It was very important for me to dislocate places and devoid them of their everyday content and context. My current artworks are much less medium-specific and very much ideas driven, so it's a kind of Deleuze-an idea. He said things like an idea in film is not an idea in literature or in philosophy. It is interesting that distinguishing between different mediums allows you to express that concept or idea in its fullness. It is quite an important aspect of my thinking and practice.

TiP: In terms of photography, how would you describe your photographs without someone seeing them?

Çavuşoğlu: I transitioned from the very classical style of tableaux painting where I used to tell stories. We would construct figurative compositions, and they would pictorialize historical facts and often depict epic scenes. The first type of photographs I started developing was what we now call constructed photography, where I worked with models in a studio environment or on location and I was very much controlling the mise-en-scène and the stories I wanted to tell, fictionalizing and constructing narratives like what I did in painting. The next step for me was engaging with everyday subjects and looking at the surrounding reality and depicting moments, subjects, or fragments that relate to my thinking. The landscape has played a very important part in my thinking. These are the kind of landscapes that I called non-places or liminal that exist in between, defining transitional and fluid spaces, or borders, which are themes that then I carried on to my photographic and then video installation practices.

Çavuşoğlu: I transitioned from the very classical style of tableaux painting where I used to tell stories. We would construct figurative compositions, and they would pictorialize historical facts and often depict epic scenes. The first type of photographs I started developing was what we now call constructed photography, where I worked with models in a studio environment or on location and I was very much controlling the mise-en-scène and the stories I wanted to tell, fictionalizing and constructing narratives like what I did in painting. The next step for me was engaging with everyday subjects and looking at the surrounding reality and depicting moments, subjects, or fragments that relate to my thinking. The landscape has played a very important part in my thinking. These are the kind of landscapes that I called non-places or liminal that exist in between, defining transitional and fluid spaces, or borders, which are themes that then I carried on to my photographic and then video installation practices.

TiP: Talk about light and lightness.

Çavuşoğlu: Light is an essential element in capturing a scene. It's very important that the illumination takes place, and reveals the subject matter, whatever we want to capture in that sense. But at the same time, once the image has been constructed and has been illuminated and we transition into the next stage, which is contextualizing that image, what I'm interested in is this notion of lightness that permits us to engage with the image without burdening and creates this immediacy of the emotional responses.

TiP: How is liminality expressed in a photograph visually?

Çavuşoğlu: Liminality has been a kind of persistent interest of mine. You're trying to capture liminality, whether it's in an image, whether it's in a sequence of images, and it's the space which exists in between the real place that's been captured and the one that we behold a mental image of or the one that we want to imagine. This is where it becomes interesting because liminality is a mental state that allows us to capture that moment that is no longer there or is somehow traceable within the image, but not necessarily visible. A photograph of a territorial border, for example, a non-place, something that doesn't belong to one country or another, will illustrate to a degree the liminality, but at the same time, I think liminality is something that is received by the audiences but not necessarily seen. That's a difficult distinction. The way the composition allows us to see beyond what's in the frame. This is something that we don't necessarily see, but we feel, or we imagine.

Çavuşoğlu: Light is an essential element in capturing a scene. It's very important that the illumination takes place, and reveals the subject matter, whatever we want to capture in that sense. But at the same time, once the image has been constructed and has been illuminated and we transition into the next stage, which is contextualizing that image, what I'm interested in is this notion of lightness that permits us to engage with the image without burdening and creates this immediacy of the emotional responses.

TiP: How is liminality expressed in a photograph visually?

Çavuşoğlu: Liminality has been a kind of persistent interest of mine. You're trying to capture liminality, whether it's in an image, whether it's in a sequence of images, and it's the space which exists in between the real place that's been captured and the one that we behold a mental image of or the one that we want to imagine. This is where it becomes interesting because liminality is a mental state that allows us to capture that moment that is no longer there or is somehow traceable within the image, but not necessarily visible. A photograph of a territorial border, for example, a non-place, something that doesn't belong to one country or another, will illustrate to a degree the liminality, but at the same time, I think liminality is something that is received by the audiences but not necessarily seen. That's a difficult distinction. The way the composition allows us to see beyond what's in the frame. This is something that we don't necessarily see, but we feel, or we imagine.

TiP: I think that that's a very good point because in a sense, what you're trying to do is to get the viewer, the person experiencing your work of art, to complete the work of art. So not everything is necessarily there. It only becomes definitive in the experience of the beholder.

Çavuşoğlu: In my early years of professional practice, there was a period at the beginning of the 1990s when I was working predominantly with photography, and I started asking myself, what is an image in an art context? What is an image in life, in art, in painting, and in spatial geometry? And to answer that question, I thought I should look at how we engage with images that we don't necessarily see but instead imagine on a mental plane. So, this is a kind of liminal state, a liminal image that is there and not there. Then I stumbled across a couple of concepts that Walter Benjamin put forward, namely Denkbild and Bildbegheren. It's the idea of images that we think about, or desire but don't necessarily see. I started pondering how I would deny the viewer the direct encounter with the subject but allow them to experience and feel something that is subliminal, something that they can imagine for themselves, allowing them that space for them to see the image mentally, to encounter it.

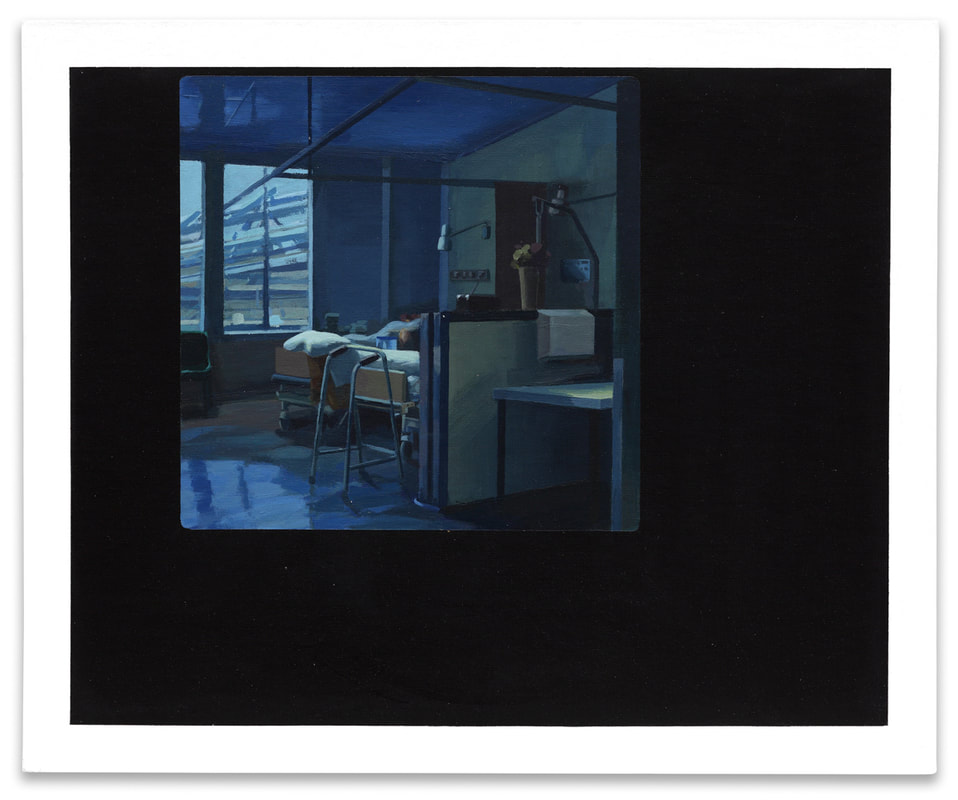

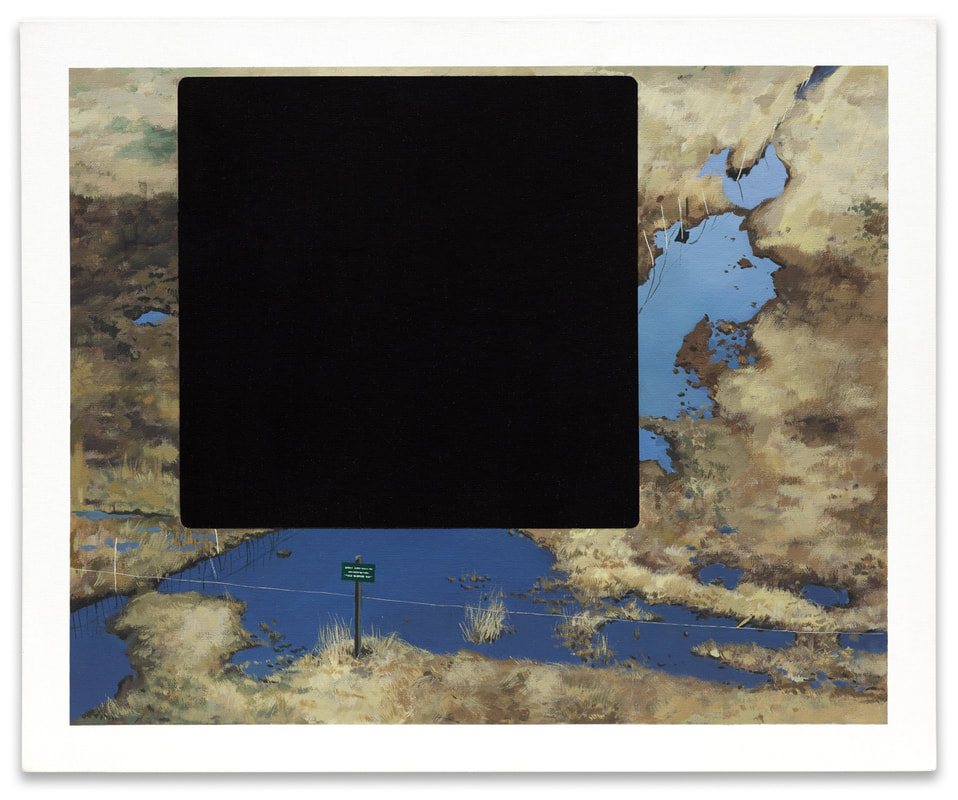

In 1998 I made a series of five paintings called Instant I-V. They were based on the idea of the Polaroid, which if you shoot with the six-by-six Hasselblad camera, the image in the Polaroid is offset from the center of the image on the plane. This was the time when the largest Polaroid camera, 20 by 24 inches, was celebrated by artists and photographers alike. I made the paintings exactly 20 by 24 inches, kind of reversing the process. Painting is a very slow undertaking. It takes time to learn and time to make. Whereas I thought, the physical 20 by 24 inch Polaroid is the fastest way of producing images. You shoot and then minutes later, you have an image that develops and then you end up with a physical object. In some cases, I painted the area where the instant image would appear, the square, like in the original Hasselblad Polaroid. In other cases that was left black, and the rest of the image was around it, blocking parts of the image. The subject matter was claustrophobic interiors, like aircraft cabins, hospital rooms, and sites of memory, juxtaposing them with very painterly exterior landscapes. The last image in the series was constructed by the superimposition of the interior onto the exterior. It is a kind of dialogue between image-making in photography and painting. I think photography for me is very important in relation to image making because it sits on the cusp of stillness and the cusp of moving, but nevertheless, it's still a very tangible image. The Instant series were concerned with the disintegration of photographic reality concerning time and form and its reconstruction in a painting.

Çavuşoğlu: In my early years of professional practice, there was a period at the beginning of the 1990s when I was working predominantly with photography, and I started asking myself, what is an image in an art context? What is an image in life, in art, in painting, and in spatial geometry? And to answer that question, I thought I should look at how we engage with images that we don't necessarily see but instead imagine on a mental plane. So, this is a kind of liminal state, a liminal image that is there and not there. Then I stumbled across a couple of concepts that Walter Benjamin put forward, namely Denkbild and Bildbegheren. It's the idea of images that we think about, or desire but don't necessarily see. I started pondering how I would deny the viewer the direct encounter with the subject but allow them to experience and feel something that is subliminal, something that they can imagine for themselves, allowing them that space for them to see the image mentally, to encounter it.

In 1998 I made a series of five paintings called Instant I-V. They were based on the idea of the Polaroid, which if you shoot with the six-by-six Hasselblad camera, the image in the Polaroid is offset from the center of the image on the plane. This was the time when the largest Polaroid camera, 20 by 24 inches, was celebrated by artists and photographers alike. I made the paintings exactly 20 by 24 inches, kind of reversing the process. Painting is a very slow undertaking. It takes time to learn and time to make. Whereas I thought, the physical 20 by 24 inch Polaroid is the fastest way of producing images. You shoot and then minutes later, you have an image that develops and then you end up with a physical object. In some cases, I painted the area where the instant image would appear, the square, like in the original Hasselblad Polaroid. In other cases that was left black, and the rest of the image was around it, blocking parts of the image. The subject matter was claustrophobic interiors, like aircraft cabins, hospital rooms, and sites of memory, juxtaposing them with very painterly exterior landscapes. The last image in the series was constructed by the superimposition of the interior onto the exterior. It is a kind of dialogue between image-making in photography and painting. I think photography for me is very important in relation to image making because it sits on the cusp of stillness and the cusp of moving, but nevertheless, it's still a very tangible image. The Instant series were concerned with the disintegration of photographic reality concerning time and form and its reconstruction in a painting.

TiP: Could you finish the sentence, “Truth in photography is…?”

Çavuşoğlu: Truth in photography is only relevant in relation to the encounter of the image with the audience because only the viewer can receive and acknowledge or determine that truthfulness. Even if it's a fictionalized image, but looks truthful to us, we can believe in it. It is the believability of an image that's quite important, whether it captures reality or not. It could be somebody else's reality; it could be an imagined reality by the maker. I'm not talking about the CGI type of reality. I'm talking about moments in life that are captured without any kind of intervention or constructed by the maker. I think that even the constructed image will have elements of truth in it because it derives from reality and comes from real life.

TiP: Sometimes in fiction, there's more truth in our ability to render the factual.

Çavuşoğlu: Absolutely, I can't agree more. There is one photograph which I took in 1996, which is a constructed image of a young woman playing the piano, covered with something that looks like a hijab, but it's not very clear in the image what kind of religion she belongs to. The story in that image is based on a real-life experience of migration, in-betweenness, placelessness, and liminality, as I mentioned earlier.

Çavuşoğlu: Truth in photography is only relevant in relation to the encounter of the image with the audience because only the viewer can receive and acknowledge or determine that truthfulness. Even if it's a fictionalized image, but looks truthful to us, we can believe in it. It is the believability of an image that's quite important, whether it captures reality or not. It could be somebody else's reality; it could be an imagined reality by the maker. I'm not talking about the CGI type of reality. I'm talking about moments in life that are captured without any kind of intervention or constructed by the maker. I think that even the constructed image will have elements of truth in it because it derives from reality and comes from real life.

TiP: Sometimes in fiction, there's more truth in our ability to render the factual.

Çavuşoğlu: Absolutely, I can't agree more. There is one photograph which I took in 1996, which is a constructed image of a young woman playing the piano, covered with something that looks like a hijab, but it's not very clear in the image what kind of religion she belongs to. The story in that image is based on a real-life experience of migration, in-betweenness, placelessness, and liminality, as I mentioned earlier.

|

The story related to this photograph was told to me by my family who immigrated from Bulgaria to Turkey in 1989. My sister used to play the piano and my father is an artist, and they were given a very limited time window by the government to leave the country and allowed a nominal amount of space to pack any belongings. However, what they decided to take with them was my sister's piano. It was an upright piano, which she played for eight years or so. I wasn't part of this process, this massive wave of migration, because I was serving in the last Bulgarian communist army at the time. And when I reunited with my family months later in Istanbul and saw the piano, they told me the story. I asked, “Why is the piano here and where are your artworks?” My father said without explaining that he locked all his artwork in his two studios in Bulgaria, but they decided to take the piano with them. They told me that the piano was taken by truck to the border, offloaded, and then pushed by hand between the border of Bulgaria and Turkey, which is kind of a big buffer zone, something like a thousand meters. And the piano was transitioned from one space into another, from one country to another, from one life into another. And I thought, well, this is very poetic, very symbolic. But I didn't know what to do. Over the years I started several different projects based on the story. The first one was the photograph, which I was talking about. The symbolic significance of the piano as a Western instrument representing liberal cultural values led me to contrast it with a young covered woman as a response to the tectonic shifts taking place in the political landscape of Turkey during the mid-nineties. I wanted to relate that image to the past and present, but also the future perhaps. And it's a constructed photograph, all the elements carefully staged. There is a sense of reality in it, but it's a different reality.

|

TiP: In some sense what you're depicting there is the truth of the piano.

Çavuşoğlu: It’s the truth of the piano, the longing for the past, but thinking about the present. Years later, I was working on a major solo exhibition at the Ludwig Forum for International Art in Germany, and the museum wanted to commission a piece. This was exactly 20 years since the exodus had taken place. And when the museum said, “We’ll commission that particular piece,” I said, “What I would like to do is really to be truthful to the story because I don't know how to tell that story. The only way to do it is to reenact it.” And we did exactly that. It took us nearly a year to get permissions from both governments to film at the border. The piece is called Liminal Crossing. It is exactly the way it was told to me. A piano arrives from the Bulgarian side of the border, offloaded from a truck, and then a family pushes the piano by hand entering Turkey through the checkpoint. We filmed from two directions. One is leaving and the other one is arriving and it's a two-screen video piece. I think it's very important because if I can retell that story in every truth, I can re-imagine it.

Çavuşoğlu: It’s the truth of the piano, the longing for the past, but thinking about the present. Years later, I was working on a major solo exhibition at the Ludwig Forum for International Art in Germany, and the museum wanted to commission a piece. This was exactly 20 years since the exodus had taken place. And when the museum said, “We’ll commission that particular piece,” I said, “What I would like to do is really to be truthful to the story because I don't know how to tell that story. The only way to do it is to reenact it.” And we did exactly that. It took us nearly a year to get permissions from both governments to film at the border. The piece is called Liminal Crossing. It is exactly the way it was told to me. A piano arrives from the Bulgarian side of the border, offloaded from a truck, and then a family pushes the piano by hand entering Turkey through the checkpoint. We filmed from two directions. One is leaving and the other one is arriving and it's a two-screen video piece. I think it's very important because if I can retell that story in every truth, I can re-imagine it.

|

|

Delve deeper |