This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the ArtistPacifico Silano is a lens-based artist whose work is an exploration of print culture, the circulation of imagery and LGBTQ identity. Born in Brooklyn, NY, he received his MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts. His work has been exhibited in solo and group shows all over the world and is in the Permanent Collection of The Museum of Modern Art. Silano received the Aaron Siskind Foundation Fellowship, the NYFA Fellowship in Photography, was a finalist for the Aperture Foundation Portfolio Prize, and was shortlisted for the Paris Photo/Aperture First Book Prize for I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine. |

|

Truth in Photography: Talk about your work and the work that's in the exhibition A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload, at the International Center of Photography.

Pacifico Silano: A lot of my work is based on image culture, particularly queer imagery that is culled from magazines and gay erotica from the post Stonewall riots to the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. My uncle passed away from complications of HIV when I was really young. And after he passed away, it was like he was erased from our family. I didn't grow up with any pictures of him or any memories of who he was because I was so young when he died. And so I started to look at media representations of gay identity, particularly around the time that my uncle was alive, and that just so happened to be gay pornography of that era. That was the more public representation of gay identity in the time period.

I started sourcing out imagery and really starting to think about these photographs that impacted my uncle's own understanding of his own identity. And then I started to look at this history of a photograph and how we really imbue an image with its own meaning. We bring our own perspective, our own experiences to a photograph, especially one that's been published and put out into the world. As photographers, we think we take a picture, and we know what it's going to be about and that's what it is. But a photograph has multiple lives, and that really started to interest me about the images that I deal with, because they started to become markers of the innumerable loss. A lot of the men in the magazines wound up passing away from complications of HIV or AIDS later on in the 90s or even the late 80s. And so a lot of the work is about loss and longing, remembrance, sensitivity. It's really about a more submissive side or idea of what a man could be. In the way that I relate to my own masculinity, and it's also really complicated, these sort of fraught representations of masculinity, and how some of them are outmoded and outdated and yet they still have this charge to them.

Pacifico Silano: A lot of my work is based on image culture, particularly queer imagery that is culled from magazines and gay erotica from the post Stonewall riots to the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. My uncle passed away from complications of HIV when I was really young. And after he passed away, it was like he was erased from our family. I didn't grow up with any pictures of him or any memories of who he was because I was so young when he died. And so I started to look at media representations of gay identity, particularly around the time that my uncle was alive, and that just so happened to be gay pornography of that era. That was the more public representation of gay identity in the time period.

I started sourcing out imagery and really starting to think about these photographs that impacted my uncle's own understanding of his own identity. And then I started to look at this history of a photograph and how we really imbue an image with its own meaning. We bring our own perspective, our own experiences to a photograph, especially one that's been published and put out into the world. As photographers, we think we take a picture, and we know what it's going to be about and that's what it is. But a photograph has multiple lives, and that really started to interest me about the images that I deal with, because they started to become markers of the innumerable loss. A lot of the men in the magazines wound up passing away from complications of HIV or AIDS later on in the 90s or even the late 80s. And so a lot of the work is about loss and longing, remembrance, sensitivity. It's really about a more submissive side or idea of what a man could be. In the way that I relate to my own masculinity, and it's also really complicated, these sort of fraught representations of masculinity, and how some of them are outmoded and outdated and yet they still have this charge to them.

I'm interested in the power of an image that already exists in the world, how it has these multiple meanings, and how we can go through these regenerative phases of history, changing the way that we relate to that photograph. It's why I don't take pictures from the physical world. Everything comes from an image of an image. I'm really very fascinated with the tactility of the photographs and the object-ness of a photograph. I think being born in the late 80s and growing up in the 90s, still having that analog world, that physicality of a magazine and of a photograph has really informed my own relationship to the medium of photography. It comes through very much in the finalized formats of my work.

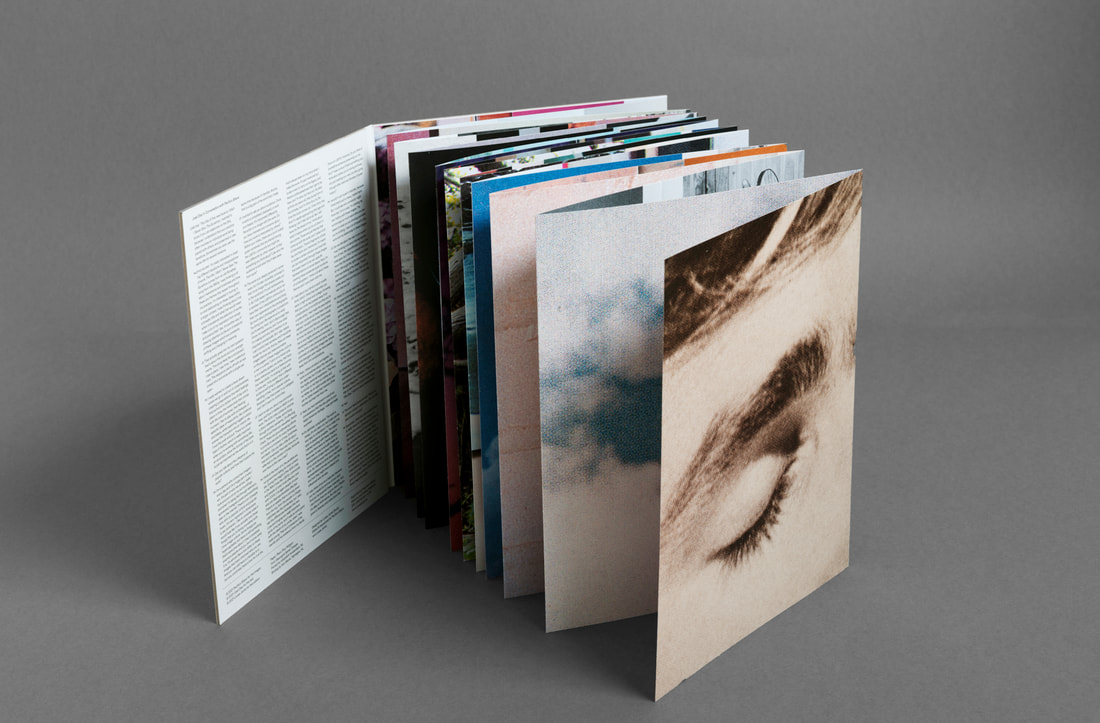

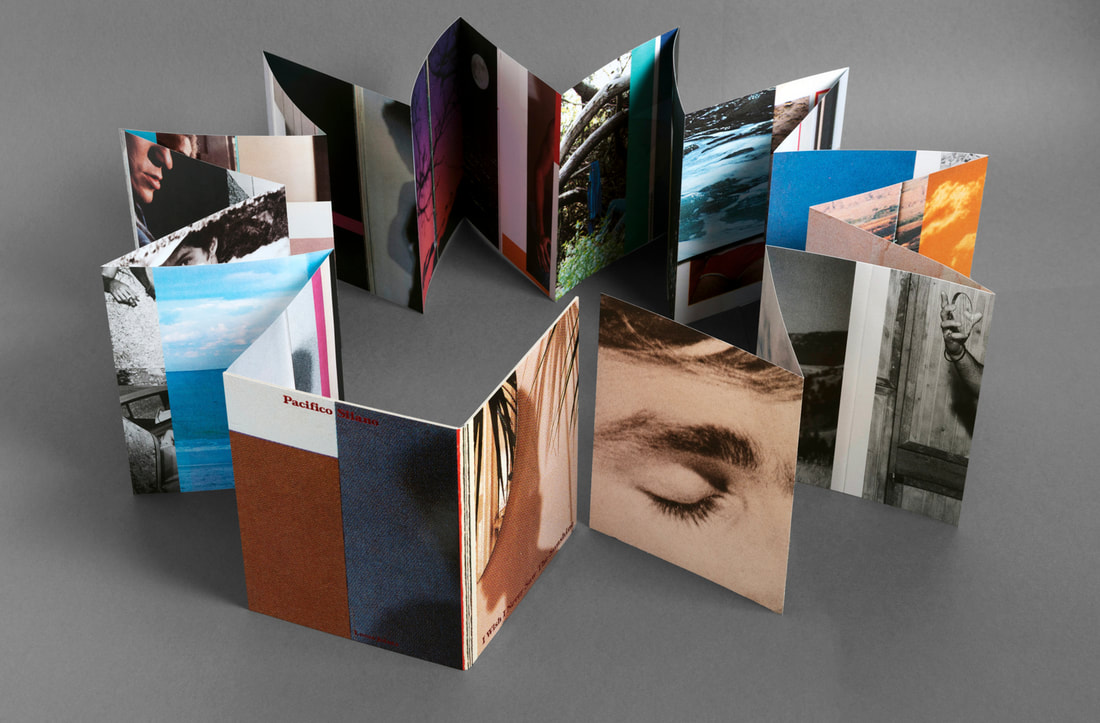

The piece that I have in A Trillion Sunsets is an artist's book. It's meant to be an art object photo book that can be read through as a traditional photographer's monograph or can be activated into this physical object that takes up space. Both emotionally and physically it really is a sort of fever dream of stepping in and out of consciousness, of a daydream of the fantasy of the images that happen on these pages, but also imbued with such sadness and melancholy. In a way, the accordion format, allowing it to physically extend and take on this physicality, really does relate back to my own image making and my installation process. So much of the work that I typically make in gallery and museum settings is layered, framed photographs on top of vinyls on the wall, a collage that I create within a space. And here in this book, it's all self-contained. It's this little 8 x 10” book that opens up and becomes so long and so much bigger than it looks on first sight.

The piece that I have in A Trillion Sunsets is an artist's book. It's meant to be an art object photo book that can be read through as a traditional photographer's monograph or can be activated into this physical object that takes up space. Both emotionally and physically it really is a sort of fever dream of stepping in and out of consciousness, of a daydream of the fantasy of the images that happen on these pages, but also imbued with such sadness and melancholy. In a way, the accordion format, allowing it to physically extend and take on this physicality, really does relate back to my own image making and my installation process. So much of the work that I typically make in gallery and museum settings is layered, framed photographs on top of vinyls on the wall, a collage that I create within a space. And here in this book, it's all self-contained. It's this little 8 x 10” book that opens up and becomes so long and so much bigger than it looks on first sight.

TiP: Complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”

Silano: Truth in photography is subjective. It all depends on where you're standing and how you see something. And in many ways, photography is not truth at all. It's kind of a lie. It's a fantasy. It's a viewpoint that we want to create, and we want to articulate to an audience. That's what makes the medium so fraught and complicated. And what’s really powerful is that everybody brings their biases, their worldview, and their experiences when they pick up a camera or when they're, in my case, collaging an image or seeing something that maybe somebody else doesn't see on first glance. And so for me, it becomes very much about life experience and biography and how we bring that to every frame of the photograph that we create, or we rework, in my case.

TiP: It seems in your work that if there is a truth, it's in the multiplicity of images.

Silano: I would say for sure, it's not something that is linear. It's not a beginning, middle, and end.

TiP: What’s not linear?

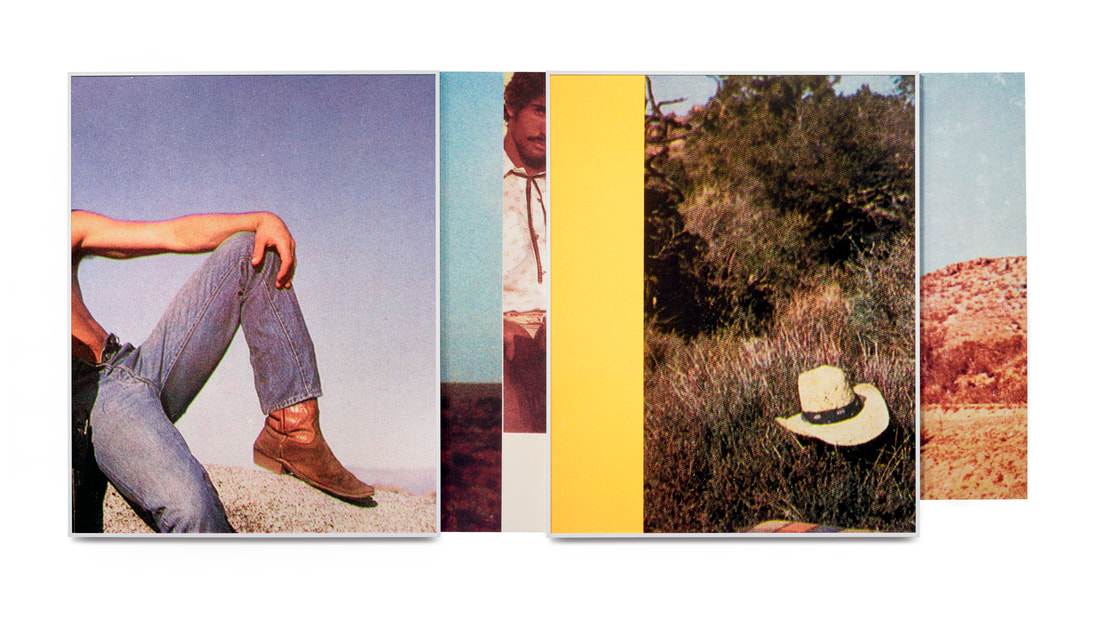

Silano: The physicality, the image, the final form of the pictures that I created. It's not necessarily beginning, middle, and end. It sort of is. I've been creating this work for a decade. Traditionally photographers work in projects where it's a portfolio of 20 images that they put out into the world. They frame them on the wall, and then they're done, and they go on to a next body of work. Whereas for me, it has really been this long journey of finding different threads that are tangentially related, where I pick up another thread and then I follow that and it leads to something else. I have a series of images that are of cowboys that are about this very Americanized, idealized version of masculinity. But they're queer because they come from vintage gay erotica. But then in the same image, I might have something that references a motorcycle or biker or the archetype of American masculinity of Rebel Without a Cause, real tropes and images that we all know from film and reading and television and photography. There are these really powerful archetypes that guide my work and I investigate that. And then I'll look at that and that will lead to something else. But they all live together. They're not hierarchical, they're not one more important than the other. They're all in support of one another and really volley off of one another because they're all part of this bigger portrait, or this bigger inquiry about masculinity, American identity, and particularly its relationship to queer identity, and how there's often these things that are at odds with one another. And that's that gray area that I'm really interested in because it's not one thing or the other. It's this strange place where they can both simultaneously exist, and how that's also related to desire. There's this complicated, almost fetishization of power that happens in a lot of these magazines and images. And normally it's an oppressor. It's a police officer, it's somebody who is physically dominant. And what does that mean? What does that say if you relate to that or you're seduced and repulsed by it at the same time? All of these things are contradictions that exist within the spaces of these images that I rework and that I'm imbuing with the lens of today that we're reading through these images of the past.

Silano: Truth in photography is subjective. It all depends on where you're standing and how you see something. And in many ways, photography is not truth at all. It's kind of a lie. It's a fantasy. It's a viewpoint that we want to create, and we want to articulate to an audience. That's what makes the medium so fraught and complicated. And what’s really powerful is that everybody brings their biases, their worldview, and their experiences when they pick up a camera or when they're, in my case, collaging an image or seeing something that maybe somebody else doesn't see on first glance. And so for me, it becomes very much about life experience and biography and how we bring that to every frame of the photograph that we create, or we rework, in my case.

TiP: It seems in your work that if there is a truth, it's in the multiplicity of images.

Silano: I would say for sure, it's not something that is linear. It's not a beginning, middle, and end.

TiP: What’s not linear?

Silano: The physicality, the image, the final form of the pictures that I created. It's not necessarily beginning, middle, and end. It sort of is. I've been creating this work for a decade. Traditionally photographers work in projects where it's a portfolio of 20 images that they put out into the world. They frame them on the wall, and then they're done, and they go on to a next body of work. Whereas for me, it has really been this long journey of finding different threads that are tangentially related, where I pick up another thread and then I follow that and it leads to something else. I have a series of images that are of cowboys that are about this very Americanized, idealized version of masculinity. But they're queer because they come from vintage gay erotica. But then in the same image, I might have something that references a motorcycle or biker or the archetype of American masculinity of Rebel Without a Cause, real tropes and images that we all know from film and reading and television and photography. There are these really powerful archetypes that guide my work and I investigate that. And then I'll look at that and that will lead to something else. But they all live together. They're not hierarchical, they're not one more important than the other. They're all in support of one another and really volley off of one another because they're all part of this bigger portrait, or this bigger inquiry about masculinity, American identity, and particularly its relationship to queer identity, and how there's often these things that are at odds with one another. And that's that gray area that I'm really interested in because it's not one thing or the other. It's this strange place where they can both simultaneously exist, and how that's also related to desire. There's this complicated, almost fetishization of power that happens in a lot of these magazines and images. And normally it's an oppressor. It's a police officer, it's somebody who is physically dominant. And what does that mean? What does that say if you relate to that or you're seduced and repulsed by it at the same time? All of these things are contradictions that exist within the spaces of these images that I rework and that I'm imbuing with the lens of today that we're reading through these images of the past.

TiP: Talk about your process. Are you making photographs of photographs or are you just appropriating images that you find?

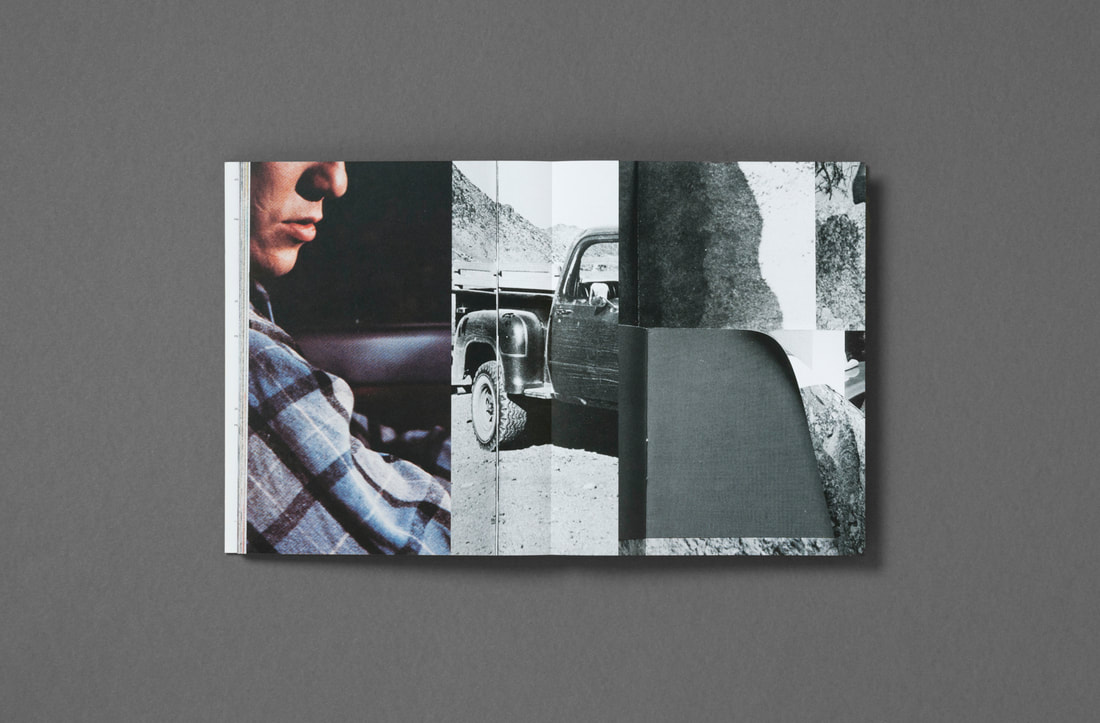

Silano: My process is very particular. I photograph on a copy stand. I use strobe lighting, and I layer things, and I collage on the base of my copy stand. I will document it with the camera, and then I bring it into my digital archive. I'll make some very light corrections, usually color balancing, cleaning up an image a little bit. I try to keep a lot of the integrity of the original image just because I like to pinpoint the physicality and the historical reference of the image of how it's aged or how it's fallen apart over time. And then I'll create a digital mockup of a collage that I'm going to create that's going to be installed typically on a gallery wall. The next step is the cropping. I crop within the crops of the images I've already made. And so, the work doesn't stop with the shutter. It continues. It goes into the process of being edited and then creating these relationships between images, photographs that are in dialog with one another, the juxtapositions, and then deciding what's going to become a vinyl, what's going to become a framed photograph? What's going to take on a larger scale in a physical space? And what's going to be really small and intimate? And how do I negotiate that between image to image? There's a lot that happens after the fact that a lot of people don't really get to know or hear about.

TiP: What do you hope is the takeaway from your photographs?

Silano: I think that there's a real softness and gentleness on the surface of the image, and then underneath that there's something that's a little darker, and that's really a perfect metaphor for American identity, right? We want to be seduced, but then the more we spend time with something, we might find ourselves repulsed from it ultimately. There's a lot of contradictions and there is no one right or wrong way of reading an image. For so long, I've been creating work that's really about memorial and about loss, and my work is growing and it's changing and it's evolving, and it's becoming a little bit more about the darker themes. The work that's on display here: there's a lot of lightness, there's a lot of sensitivity, there's a lot of melancholy in that work. And the work is changing. I'm looking at the stuff that I've been cropping out of those collages in those photographs for the last decade. And I'm thinking about, “How does that work live side by side by what I've created for the last ten years?” I recognize that I can't control fully the narrative of the image because that's not how photography functions. It really is how somebody moves through the world, and what they make of the references that these pictures bring up. Some people are going to have really strong emotional attachments to some of these photographs, and other people, it might not resonate as much, and that's totally okay. I create photographs because it's something that feels innate and something that I have to do because I have such a curiosity about the way an image functions and particularly how it impacts my own understanding of my own identity. It really is something that every time I try to put it down, I get pulled back to it. Every time I say, “I'm going to work on something different,” for whatever reason, I always come back to the source material.

Silano: My process is very particular. I photograph on a copy stand. I use strobe lighting, and I layer things, and I collage on the base of my copy stand. I will document it with the camera, and then I bring it into my digital archive. I'll make some very light corrections, usually color balancing, cleaning up an image a little bit. I try to keep a lot of the integrity of the original image just because I like to pinpoint the physicality and the historical reference of the image of how it's aged or how it's fallen apart over time. And then I'll create a digital mockup of a collage that I'm going to create that's going to be installed typically on a gallery wall. The next step is the cropping. I crop within the crops of the images I've already made. And so, the work doesn't stop with the shutter. It continues. It goes into the process of being edited and then creating these relationships between images, photographs that are in dialog with one another, the juxtapositions, and then deciding what's going to become a vinyl, what's going to become a framed photograph? What's going to take on a larger scale in a physical space? And what's going to be really small and intimate? And how do I negotiate that between image to image? There's a lot that happens after the fact that a lot of people don't really get to know or hear about.

TiP: What do you hope is the takeaway from your photographs?

Silano: I think that there's a real softness and gentleness on the surface of the image, and then underneath that there's something that's a little darker, and that's really a perfect metaphor for American identity, right? We want to be seduced, but then the more we spend time with something, we might find ourselves repulsed from it ultimately. There's a lot of contradictions and there is no one right or wrong way of reading an image. For so long, I've been creating work that's really about memorial and about loss, and my work is growing and it's changing and it's evolving, and it's becoming a little bit more about the darker themes. The work that's on display here: there's a lot of lightness, there's a lot of sensitivity, there's a lot of melancholy in that work. And the work is changing. I'm looking at the stuff that I've been cropping out of those collages in those photographs for the last decade. And I'm thinking about, “How does that work live side by side by what I've created for the last ten years?” I recognize that I can't control fully the narrative of the image because that's not how photography functions. It really is how somebody moves through the world, and what they make of the references that these pictures bring up. Some people are going to have really strong emotional attachments to some of these photographs, and other people, it might not resonate as much, and that's totally okay. I create photographs because it's something that feels innate and something that I have to do because I have such a curiosity about the way an image functions and particularly how it impacts my own understanding of my own identity. It really is something that every time I try to put it down, I get pulled back to it. Every time I say, “I'm going to work on something different,” for whatever reason, I always come back to the source material.

Background wise, my mother and my father ran an adult novelty store when I was in high school and college. So there was a different relationship to pornography and the commerce of sexuality. I know that that has had an impact in the way that I relate to the subject matter. It's not the typical gay man who's making work with erotica because that's the sexualized cliche. It really is something that is part of my own biography. It's something that I relate to in a different way. Having that be a part of the bigger picture is really important for people to understand it, for them to know why I'm working with this material. It started off with the loss of my uncle and really exploring what it was like to be a gay man of his generation. And then I started to realize, “Oh, wait a minute, this is so much more than that.” It's also about my own biography. It's about my own relationship to myself and my sexuality and my own masculinity.

TiP: How do you visualize loss?

Silano: I think you visualize loss through physical voids. Physical and emotional voids. If there's an image that can conjure that, I'm always after that, and I'm trying to find ways to bring that to the forefront of an image. I have spent a lot of time creating images that are devoid or are obscured. So you don't get to see the full face, you don't get to see the full body. There is never nudity in my work. It's very rare. It's the transformation of the source material that becomes really important in the process. And it's a way of pinpointing a humanity within the work. These are people.

TiP: How do you visualize loss?

Silano: I think you visualize loss through physical voids. Physical and emotional voids. If there's an image that can conjure that, I'm always after that, and I'm trying to find ways to bring that to the forefront of an image. I have spent a lot of time creating images that are devoid or are obscured. So you don't get to see the full face, you don't get to see the full body. There is never nudity in my work. It's very rare. It's the transformation of the source material that becomes really important in the process. And it's a way of pinpointing a humanity within the work. These are people.

TiP: It seems like your approach to photography is trying to push the limits of what's possible with the medium. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Silano: I'm really passionate about the object-ness of the photograph, the sort of physical dimensions of this flat surface that can take on shape and form and be installed and reconsidered. All of these unique, different ways gives the medium this weight to it that one doesn't necessarily expect. In digital age that we live in, we're so inundated with photographs on screens on our iPhones or iPads, where we're constantly scrolling through them, and there's not the physical presence in the photograph. There is something that we lose through the touch screen. And so my work really needs to be experienced in person. Even just the print matrix dots of the magazines that I'm sourcing from, they become this really important part of the final image. They abstract the photograph and they fall apart in this really beautiful way, and they become this texture that becomes this secondary character in my work. Being able to experience something I've done on a wall or in a space and an installation, really is so important for me to push the limits of the photograph, of seeing how far we can go with the way that it is displayed and the way that we interact with an image.

Silano: I'm really passionate about the object-ness of the photograph, the sort of physical dimensions of this flat surface that can take on shape and form and be installed and reconsidered. All of these unique, different ways gives the medium this weight to it that one doesn't necessarily expect. In digital age that we live in, we're so inundated with photographs on screens on our iPhones or iPads, where we're constantly scrolling through them, and there's not the physical presence in the photograph. There is something that we lose through the touch screen. And so my work really needs to be experienced in person. Even just the print matrix dots of the magazines that I'm sourcing from, they become this really important part of the final image. They abstract the photograph and they fall apart in this really beautiful way, and they become this texture that becomes this secondary character in my work. Being able to experience something I've done on a wall or in a space and an installation, really is so important for me to push the limits of the photograph, of seeing how far we can go with the way that it is displayed and the way that we interact with an image.

I was able to do that with the book on a smaller scale, and it was really exciting for me because it really requires touch. It really requires people to page through the photographs in a similar manner that I do when I'm creating my images. And it encourages play and encourages people to move the accordion out and move it in and arrange it in ways and see relationships between images that you wouldn't see if you just page through on a cursory view through the book, which you can go through from page to page. Even just working in the accordion format was a new iteration of images that I've already installed in galleries and installed in exhibitions. And then putting it back into this format of a book, it becomes a whole other different thing. At this point, it's on its third or fourth iteration of its life, and that, to me, is so exciting about a photograph, that it could have all of these reinterpretations, all of these multiple lives, all of these different ways of functioning. I'm creating different collages that are happening in the book that will never happen on a wall, that will never happen in an exhibition space. So, I thought it was really exciting when David Campany invited me to be part of A Trillion Sunsets, because he wanted to have the book as the representative of my body of work. At first, I was like, “Oh, that's such a curious choice.” But then I thought more about how it's such a democratic choice as well. People can go out and they can get the book and they can hold it in their home, and they could put it on their coffee table. Or they can extend it and put it on a shelf where they can show it to their friends, or look at this object, look at this thing full of color. But also, then my images start to operate in this different way and this different level, and that becomes really, really exciting to me.

TiP: So is this book unique or is it multiples?

Silano: It's multiples. It's been published by a book publisher, Loose Joints, in Marseille, France. They did a fantastic job with the publication, and they were such a dream to work with on this book. And the life of the book has really taken off, and it's gotten a lot of really great accolades that I'm so appreciative of. But, even seeing the way that people play with the book at home and display or choose to photograph it and to share on Instagram is so different from the way that I would. And I think that that is just the way that we all again have different relationships to photographs. Does the person page through the book as if it's just a monograph as a simple photo book? Or do they prop it upright? Do they look at it as a sculptural art object? In many ways, it's kind of a mini exhibition. It's something that was born out of COVID. Not being able to physically go to my show, not being able for people to see the work other than a documentation photograph on a screen. It's something that people get to take home with them. It's a really great way for the images to function on this whole other level.

Silano: It's multiples. It's been published by a book publisher, Loose Joints, in Marseille, France. They did a fantastic job with the publication, and they were such a dream to work with on this book. And the life of the book has really taken off, and it's gotten a lot of really great accolades that I'm so appreciative of. But, even seeing the way that people play with the book at home and display or choose to photograph it and to share on Instagram is so different from the way that I would. And I think that that is just the way that we all again have different relationships to photographs. Does the person page through the book as if it's just a monograph as a simple photo book? Or do they prop it upright? Do they look at it as a sculptural art object? In many ways, it's kind of a mini exhibition. It's something that was born out of COVID. Not being able to physically go to my show, not being able for people to see the work other than a documentation photograph on a screen. It's something that people get to take home with them. It's a really great way for the images to function on this whole other level.

|

|

|