|

|

Charles Dee Mitchell has a large collection of conflict photography that includes border and civil rights photographs as well as well as images of mostly 21st century military conflict. The Museum of Fine Arts Houston has accepted this ongoing collection as a promised gift. Truth in Photography's Alan Govenar spoke with Mitchell and Kristen Gresh (Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Senior Curator of Photographs at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) about his collection. |

|

Alan Govenar: Talk a little bit about how you became specifically drawn to conflict photography and what propelled your collection.

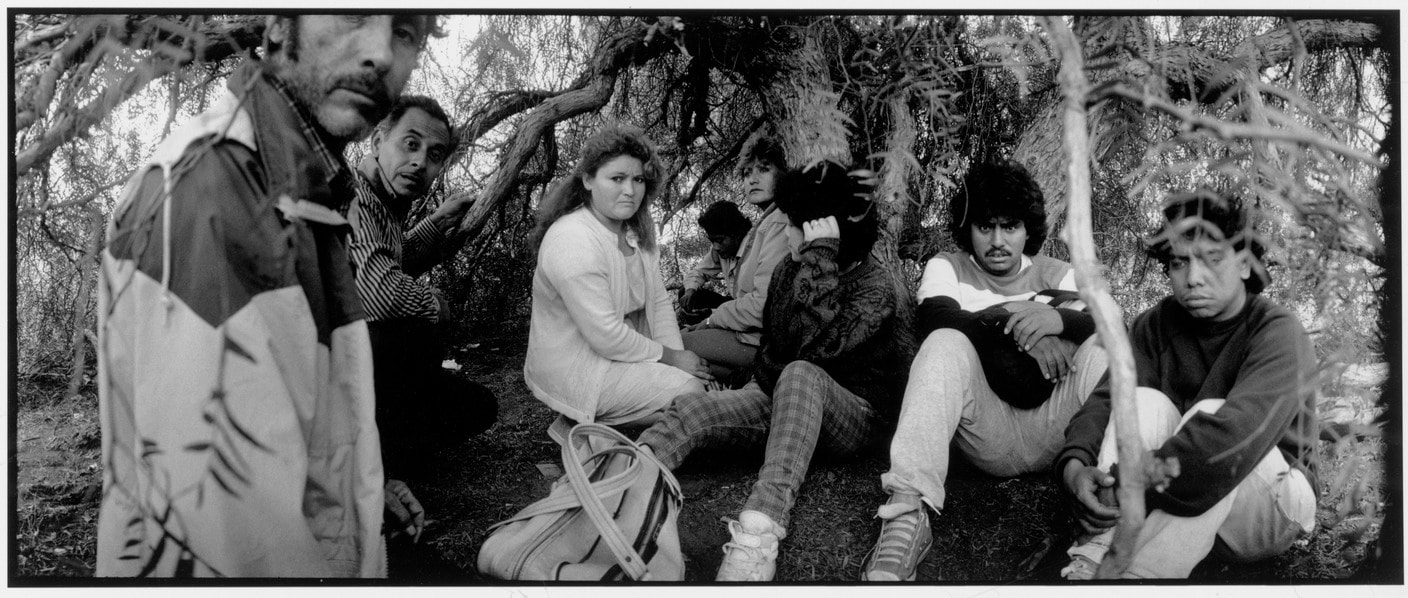

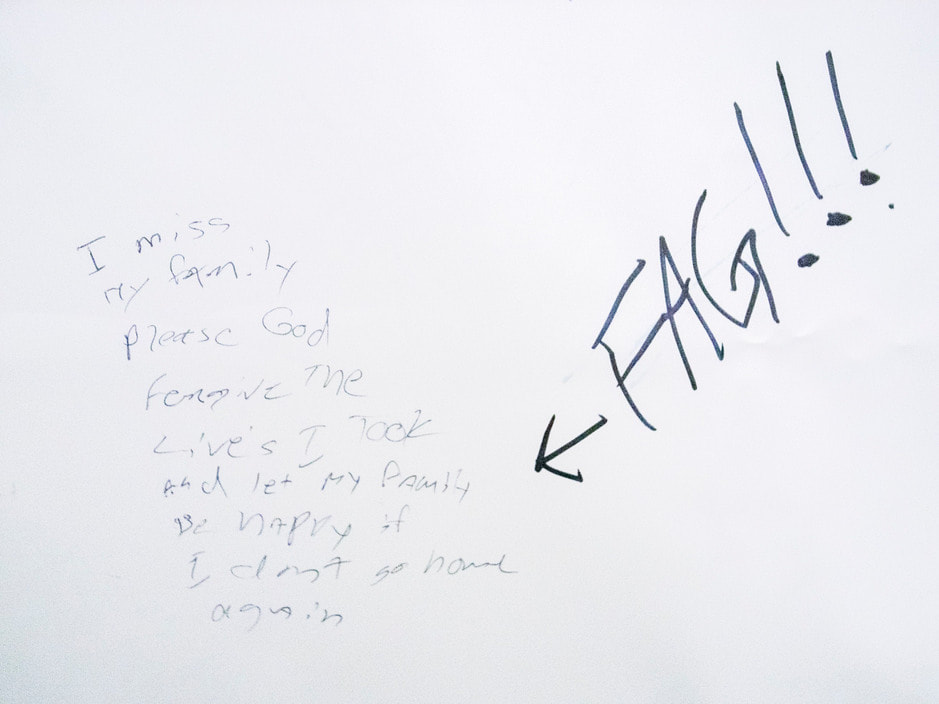

Mitchell: I've always collected photography, along with works on paper, and a few other things that come my way. But photography had always been a focus of the collection, and it was always documentary photography or what would be considered documentary as opposed to art gallery photography. When I was looking at the James Natchwey Inferno book, I wondered if it was even possible to buy these photographs, or where they were. A photography dealer here in Dallas called Magnum, and they said the photographs are available in 16” x 20” for twelve hundred dollars signed, but not editioned. Compared to what I was being told in other places about other art, I thought I should really look into this. I could buy the world's greatest current living war photographer and I could buy several of them, in fact. So, I bought three. And that started the ball rolling. About that time, Natchwey left Magnum to start the VII group, and I would call the VII group to buy prints, and every time I called there was somebody else in charge of prints sales, and they always wanted me to call back when they were better organized. And they finally signed with the gallery to handle print sales. And so, I suddenly had a small collection of very good photographs, by names that, in some cases, were even new to me, because I hadn't been looking that long, but are some of the most impressive things I have. And from there, at Fotofest, I often see people like Debi Cornwall, or Rania Matar, and Diana Matar as well, who just really stand out. And I follow up on them, and often they don't have representation yet, so you buy them directly from the studio. And it's just developed from that. Now what has happened is because so much of it was focused on 21st century conflicts, I had seen so much of that work after a while, that I realized the collection had to take on some other dimensions to stay interesting for me, to evolve. And so, I started looking at photographs from the US-Mexico border and started developing that as a collection. Once I stayed within conflict instead of war photography, the border work made sense. I have some civil rights based work, and some more recent images of police violence. In fact, I have photographs from January 6th, as well, from Peter van Agtmael.

Mitchell: I've always collected photography, along with works on paper, and a few other things that come my way. But photography had always been a focus of the collection, and it was always documentary photography or what would be considered documentary as opposed to art gallery photography. When I was looking at the James Natchwey Inferno book, I wondered if it was even possible to buy these photographs, or where they were. A photography dealer here in Dallas called Magnum, and they said the photographs are available in 16” x 20” for twelve hundred dollars signed, but not editioned. Compared to what I was being told in other places about other art, I thought I should really look into this. I could buy the world's greatest current living war photographer and I could buy several of them, in fact. So, I bought three. And that started the ball rolling. About that time, Natchwey left Magnum to start the VII group, and I would call the VII group to buy prints, and every time I called there was somebody else in charge of prints sales, and they always wanted me to call back when they were better organized. And they finally signed with the gallery to handle print sales. And so, I suddenly had a small collection of very good photographs, by names that, in some cases, were even new to me, because I hadn't been looking that long, but are some of the most impressive things I have. And from there, at Fotofest, I often see people like Debi Cornwall, or Rania Matar, and Diana Matar as well, who just really stand out. And I follow up on them, and often they don't have representation yet, so you buy them directly from the studio. And it's just developed from that. Now what has happened is because so much of it was focused on 21st century conflicts, I had seen so much of that work after a while, that I realized the collection had to take on some other dimensions to stay interesting for me, to evolve. And so, I started looking at photographs from the US-Mexico border and started developing that as a collection. Once I stayed within conflict instead of war photography, the border work made sense. I have some civil rights based work, and some more recent images of police violence. In fact, I have photographs from January 6th, as well, from Peter van Agtmael.

Police take back control of the Capitol. Following an inflammatory speech by President Trump, protestors objecting to the certification of Joe Biden by Congress storm the Capitol. They were briefly blocked by police before gaining entry, and wreaked havoc before being expelled with few arrests. One protestor was shot and killed. Washington, D.C., January 6, 2021. © Peter van Agtmael / Magnum Photos

Govenar: For you, as a collector, but also as a critic and a historian in your own right, what are you looking for in these photographs?

Mitchell: One thing I really hope to do is buy at least two or three photographs of the same incident, so that there is a narrative developed, you can begin to put in context. Often you need the catalogue entries to tell you exactly where you are, but hanging on the wall or if they were exhibited, you can reconstruct the context for them. So, like the Gary Knight photographs of going into Baghdad. It starts from the bridge outside of the city and goes into the city, and it shows the first casualties actually of the American troops. That's what I'm really looking for is some way to let the photographs create the context, so they’re not just stray images.

Govenar: Do you think these photographs are conveying the truth of conflict?

Mitchell: They have a good chance to be. I don't go searching for the most horrific images, but on the question of truth, obviously, they tend to be from the American angle, or the European Western angle, because that’s who the photographers are. But as photographers who've been engaged with these situations for decades, you would hope they have a sense of respect for everyone involved, and that they are telling the truth in that way. People are questioning the Robert Frank photograph of the Spanish soldier. They can all be challenged, I'm sure.

Gresh: As a collector, do you purchase images before you've seen prints of them?

Mitchell: The photographers that I know would not let a bad print out of the studio. I don't think I've ever been disappointed, or something was not what I expected it to be, whenever it came. In fact, with Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, who has the photograph with the very graphic helicopter attack, he really didn't know how to handle it. But I finally asked if he would just send the files and we would print them in New York. And in that case, we had another photographer that he worked with who was using the same printer. He signed off on them. I think maybe that's the only time that happened, I think I pushed anybody else about printing them in the States and they didn't want to do it.

Govenar: Conflict photography raises difficult questions about ethics. Certain conflict photographs become iconic, and they affect the way in which we understand and remember what happened. One of the points that Clément Chéroux has made about 9/11 is that photographers, when thrust into conflict, have a mental image of other conflict photographs. So the flag in the rubble at 9/11 is Iwo Jima. The framing of these photographs is so interesting, because how do they become evocative? Are these photographs made because they want to elicit a specific kind of response? And is that response necessarily what really happened, or is it so totally subjective that it has a kind of social purpose? Or are the aesthetics the primary focus?

Mitchell: I think the aesthetics. I can't speak for what's happening as the photographer takes the photograph. Well, I can, kind of, but their aesthetics certainly come into it when I'm looking at them because I'm going to own them, I expect them to go to a museum. They're going to be blown up, they're going to be larger than they were ever intended to for the original publications they went to. So, they have to hold up as that larger image. I remember when I bought the Natchweys, I was reading an interview where he was answering somebody who had questioned the photographs, and he says, “These wouldn't be more true if they were ugly.” And also, they wouldn't be remembered. They wouldn't hold up other than as documents of the moment. To get beyond that, I think there has to be an aesthetic behind them. Having said that, yes, you assume the photographers have seen every photograph ever taken, just like so many of us have. It's not like they can totally wipe them out of their mind. There are some cliches of conflict photography, and I'm sure I own some of them, too, but the women standing in the rubble, the young child center stage of the photograph, looking up at the camera. Those are out there, and everybody takes them. And also, I've noticed that some better photographers take better versions of those pictures than other people do. But it is something of a cliche, whenever you see them, but also, they are producing these photographs, not to sell to me, but to sell for their agencies, to sell to publications. And so that child looking up at the photographer is almost guaranteed the cover of the Sunday magazine. But I know, in some cases, I'm sure I've bought photographs that they never expected to sell to publications. Although it is interesting to add, at some international locations, when I was there for the book business I was in, the European photographs of American led conflicts were full of images that you would never see in the states. So that's another question about the truth of it. There are different versions of the truth in that case. I don’t know if there is some alternate truth. Let 50 years decide that question, instead of trying to say that this is not a true image of the conflict now, two years after it was taken.

Mitchell: One thing I really hope to do is buy at least two or three photographs of the same incident, so that there is a narrative developed, you can begin to put in context. Often you need the catalogue entries to tell you exactly where you are, but hanging on the wall or if they were exhibited, you can reconstruct the context for them. So, like the Gary Knight photographs of going into Baghdad. It starts from the bridge outside of the city and goes into the city, and it shows the first casualties actually of the American troops. That's what I'm really looking for is some way to let the photographs create the context, so they’re not just stray images.

Govenar: Do you think these photographs are conveying the truth of conflict?

Mitchell: They have a good chance to be. I don't go searching for the most horrific images, but on the question of truth, obviously, they tend to be from the American angle, or the European Western angle, because that’s who the photographers are. But as photographers who've been engaged with these situations for decades, you would hope they have a sense of respect for everyone involved, and that they are telling the truth in that way. People are questioning the Robert Frank photograph of the Spanish soldier. They can all be challenged, I'm sure.

Gresh: As a collector, do you purchase images before you've seen prints of them?

Mitchell: The photographers that I know would not let a bad print out of the studio. I don't think I've ever been disappointed, or something was not what I expected it to be, whenever it came. In fact, with Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, who has the photograph with the very graphic helicopter attack, he really didn't know how to handle it. But I finally asked if he would just send the files and we would print them in New York. And in that case, we had another photographer that he worked with who was using the same printer. He signed off on them. I think maybe that's the only time that happened, I think I pushed anybody else about printing them in the States and they didn't want to do it.

Govenar: Conflict photography raises difficult questions about ethics. Certain conflict photographs become iconic, and they affect the way in which we understand and remember what happened. One of the points that Clément Chéroux has made about 9/11 is that photographers, when thrust into conflict, have a mental image of other conflict photographs. So the flag in the rubble at 9/11 is Iwo Jima. The framing of these photographs is so interesting, because how do they become evocative? Are these photographs made because they want to elicit a specific kind of response? And is that response necessarily what really happened, or is it so totally subjective that it has a kind of social purpose? Or are the aesthetics the primary focus?

Mitchell: I think the aesthetics. I can't speak for what's happening as the photographer takes the photograph. Well, I can, kind of, but their aesthetics certainly come into it when I'm looking at them because I'm going to own them, I expect them to go to a museum. They're going to be blown up, they're going to be larger than they were ever intended to for the original publications they went to. So, they have to hold up as that larger image. I remember when I bought the Natchweys, I was reading an interview where he was answering somebody who had questioned the photographs, and he says, “These wouldn't be more true if they were ugly.” And also, they wouldn't be remembered. They wouldn't hold up other than as documents of the moment. To get beyond that, I think there has to be an aesthetic behind them. Having said that, yes, you assume the photographers have seen every photograph ever taken, just like so many of us have. It's not like they can totally wipe them out of their mind. There are some cliches of conflict photography, and I'm sure I own some of them, too, but the women standing in the rubble, the young child center stage of the photograph, looking up at the camera. Those are out there, and everybody takes them. And also, I've noticed that some better photographers take better versions of those pictures than other people do. But it is something of a cliche, whenever you see them, but also, they are producing these photographs, not to sell to me, but to sell for their agencies, to sell to publications. And so that child looking up at the photographer is almost guaranteed the cover of the Sunday magazine. But I know, in some cases, I'm sure I've bought photographs that they never expected to sell to publications. Although it is interesting to add, at some international locations, when I was there for the book business I was in, the European photographs of American led conflicts were full of images that you would never see in the states. So that's another question about the truth of it. There are different versions of the truth in that case. I don’t know if there is some alternate truth. Let 50 years decide that question, instead of trying to say that this is not a true image of the conflict now, two years after it was taken.

Gresh: You have such a wide range of photographs about conflict. How is it that you're coming to new areas of conflict? Is it through the photographer or are you following what's happening, and then you find the photographer? How does your search process work?

Mitchell: Some things I see in newspapers. Sometimes I see a book already in print and try to track down how to contact the photographer, or I see them on their websites. And so the great range of things are basically based on the wide variety of what I see, and also the fact that going in depth, I'd rather buy more photographs by the same photographer than trying to just find more and more photographs of these kind of incidents. When I saw in the New York Times the photographs of our troops sort of sleeping in the Capitol building in Washington, I thought I should track one of those down, but then I saw twelve of them by different photographers. And all of them remarkably similar. And they tended to be photographers I didn't know, or they were staff photographers for the New York Times. For the collection, what I finally ended up buying was Peter van Agtmael, perhaps because I knew that I already had photographs by him.

Gresh: When you buy these you have the intention for them to ultimately go to museums. In what way do you live with this collection? Do you have these on your walls? Are they in flat files? I think about the sort of beauty of conflict and the tension that we see. How do we live with these tense images that are documenting moments of conflict and time?

Mitchell: This comes up often, but I will say I have a lot of them up at any one time, usually. In my house, there's an office area over the garage, and that's always where I show the photographs. So no, they're not in the dining room or the guest room, but I do have them up. And some people ask me, “How can you stand to be around them?” And I just don't know what to say to that, because I'm so respectful of the work that's goes into producing them and the image that comes out of it, that it doesn’t cross my mind not to not to have it up, but I wouldn't have it up in the house. And some people don't want to look at it at all. Which is always kind of interesting.

Gresh: Are there moments where you've seen these things exhibited on the wall and you've been attracted?

Mitchell: I seldom see these types of images exhibited unless it's an entire war show. I've seen galleries showing this kind of work, or heard about the way they presented it, and it just seems so wrong to me. There was a European gallery showing Sergey Ponomarev works. There's one really wrenching photograph of two men hugging one another, and they've just learned that their brother died. And it was definitely one of the best photographs out of the group that were being shown. But the European gallery that was going to show the work, they were very excited about that image, because they had decided to produce something like 50 inches by 35. It was going to be this huge photograph, which just seemed in poor taste to me. Suddenly, I see the intimacy of the encounter was traded for a gross theatricality of the presentation. I've run into that one other time, where somebody took some photographs that were very intimate and they were being shown double sized of what they should have been.

Mitchell: Some things I see in newspapers. Sometimes I see a book already in print and try to track down how to contact the photographer, or I see them on their websites. And so the great range of things are basically based on the wide variety of what I see, and also the fact that going in depth, I'd rather buy more photographs by the same photographer than trying to just find more and more photographs of these kind of incidents. When I saw in the New York Times the photographs of our troops sort of sleeping in the Capitol building in Washington, I thought I should track one of those down, but then I saw twelve of them by different photographers. And all of them remarkably similar. And they tended to be photographers I didn't know, or they were staff photographers for the New York Times. For the collection, what I finally ended up buying was Peter van Agtmael, perhaps because I knew that I already had photographs by him.

Gresh: When you buy these you have the intention for them to ultimately go to museums. In what way do you live with this collection? Do you have these on your walls? Are they in flat files? I think about the sort of beauty of conflict and the tension that we see. How do we live with these tense images that are documenting moments of conflict and time?

Mitchell: This comes up often, but I will say I have a lot of them up at any one time, usually. In my house, there's an office area over the garage, and that's always where I show the photographs. So no, they're not in the dining room or the guest room, but I do have them up. And some people ask me, “How can you stand to be around them?” And I just don't know what to say to that, because I'm so respectful of the work that's goes into producing them and the image that comes out of it, that it doesn’t cross my mind not to not to have it up, but I wouldn't have it up in the house. And some people don't want to look at it at all. Which is always kind of interesting.

Gresh: Are there moments where you've seen these things exhibited on the wall and you've been attracted?

Mitchell: I seldom see these types of images exhibited unless it's an entire war show. I've seen galleries showing this kind of work, or heard about the way they presented it, and it just seems so wrong to me. There was a European gallery showing Sergey Ponomarev works. There's one really wrenching photograph of two men hugging one another, and they've just learned that their brother died. And it was definitely one of the best photographs out of the group that were being shown. But the European gallery that was going to show the work, they were very excited about that image, because they had decided to produce something like 50 inches by 35. It was going to be this huge photograph, which just seemed in poor taste to me. Suddenly, I see the intimacy of the encounter was traded for a gross theatricality of the presentation. I've run into that one other time, where somebody took some photographs that were very intimate and they were being shown double sized of what they should have been.

Govenar: Kristen, as a photographic curator, what is the appropriate size of images of conflict photography? And how do we know that that's the appropriate size?

Gresh: It's a really interesting, larger question in terms of what I consider my role versus what I feel is the photographer's role. I with my colleagues at the MFA, we will meet with a photographer and we see photographs of all different sizes. I would never want to influence the photographer's view of how they print their work. I feel that my job is to really be able to record and preserve a photographer's vision at the time they took the photograph. So if they decide that they want to do this 16 by 20 or 40 by 50, I don't feel like I should step in and make any comment. Look at Paolo Pellegrin's images. The really dark ones that he took in western Africa are really big, and I think they're really powerful that way, because they invite you in in this really intense way. Whereas some other ones, I completely agree with you that this Sergey Ponomarev would maybe be too big. So, I think it does depend on the image, but it’s also the photographer's vision. We talk about vintage work. We want to capture what the photographer's vision at the time they took the photograph was.

Govenar: It's tough for some people to look at conflict photography, but then again, it's tough for people to accept the reality of what's going on every day. The faux reality is sometimes easier to take.

Mitchell: Whenever I bought the first Natchwey photographs and they were at the frame shop I use, they had them up where they display things in the frame shop. When I went by they talked about the reactions they were getting to them, and the best one was somebody who had spent time looking at them and obviously was concerned or upset by them. But her first question was “Are these off of a movie set?” That was sort of her distancing device, I think.

Govenar: Kristen, you acquire photographs, and you can have this dialogue with the photographers and the makers. As a curator, you need to put them on the wall and then you think about the viewer and the viewer response. When the photographs are difficult like this, on these subjects, how do you organize them? How do you rate them? How do you put them together so the individual pieces come together as an aggregate that creates a whole that is more than the individual image?

Gresh: It's a great question, and something that I really think a lot about. A couple of examples: in one exhibition that I did a few years ago in 2019 called Viewpoints. One section was called Conflicts and Crises, and I had some really intense images that were conflict photographs, ranging from civil rights to war photographs. There were nine sections in the show. I intentionally didn't want it to be the first one or the last one. The whole exhibition kind of flowed and it wasn't meant to be strict. Things could overlap. But we made a space that I don't think the visitor would have known how intentional it was, but you could just walk by this little inlet if you needed. As you said, the sort of distancing device. Or you could go into it and have a closer look at some D-Day images, at some civil rights images, at the press print of a Vietnamese soldier being shot. It was really an intense image, but you had to walk around, and you could have this moment to engage. I do spend a lot of time thinking about the photographer's perspective and what they've done, and then also the viewer, wanting to fully be sensitive to the many different perspectives and reactions that the viewer might have, but sort of creating the most welcoming and safe place without discouraging anyone.

Gresh: It's a really interesting, larger question in terms of what I consider my role versus what I feel is the photographer's role. I with my colleagues at the MFA, we will meet with a photographer and we see photographs of all different sizes. I would never want to influence the photographer's view of how they print their work. I feel that my job is to really be able to record and preserve a photographer's vision at the time they took the photograph. So if they decide that they want to do this 16 by 20 or 40 by 50, I don't feel like I should step in and make any comment. Look at Paolo Pellegrin's images. The really dark ones that he took in western Africa are really big, and I think they're really powerful that way, because they invite you in in this really intense way. Whereas some other ones, I completely agree with you that this Sergey Ponomarev would maybe be too big. So, I think it does depend on the image, but it’s also the photographer's vision. We talk about vintage work. We want to capture what the photographer's vision at the time they took the photograph was.

Govenar: It's tough for some people to look at conflict photography, but then again, it's tough for people to accept the reality of what's going on every day. The faux reality is sometimes easier to take.

Mitchell: Whenever I bought the first Natchwey photographs and they were at the frame shop I use, they had them up where they display things in the frame shop. When I went by they talked about the reactions they were getting to them, and the best one was somebody who had spent time looking at them and obviously was concerned or upset by them. But her first question was “Are these off of a movie set?” That was sort of her distancing device, I think.

Govenar: Kristen, you acquire photographs, and you can have this dialogue with the photographers and the makers. As a curator, you need to put them on the wall and then you think about the viewer and the viewer response. When the photographs are difficult like this, on these subjects, how do you organize them? How do you rate them? How do you put them together so the individual pieces come together as an aggregate that creates a whole that is more than the individual image?

Gresh: It's a great question, and something that I really think a lot about. A couple of examples: in one exhibition that I did a few years ago in 2019 called Viewpoints. One section was called Conflicts and Crises, and I had some really intense images that were conflict photographs, ranging from civil rights to war photographs. There were nine sections in the show. I intentionally didn't want it to be the first one or the last one. The whole exhibition kind of flowed and it wasn't meant to be strict. Things could overlap. But we made a space that I don't think the visitor would have known how intentional it was, but you could just walk by this little inlet if you needed. As you said, the sort of distancing device. Or you could go into it and have a closer look at some D-Day images, at some civil rights images, at the press print of a Vietnamese soldier being shot. It was really an intense image, but you had to walk around, and you could have this moment to engage. I do spend a lot of time thinking about the photographer's perspective and what they've done, and then also the viewer, wanting to fully be sensitive to the many different perspectives and reactions that the viewer might have, but sort of creating the most welcoming and safe place without discouraging anyone.

Govenar: What do we get out of looking at these pictures? Are we trying to find some deeper truth in that reality? Why put them on view in this manner, because obviously, you're re-contextualizing them, putting them on the wall, whether it's in your home gallery or in a museum? Why do it? What's the takeaway?

Gresh: For me, it feels deeply important to bring the world into the museum, to open people's eyes to a lot of things. And I think that conflict photography is a way to raise awareness on the human level, taking out politics entirely, but thinking about injustices in a larger sense. I don't necessarily think of an event and then say, “Oh, well, we need to get that event publicized.” It's more thinking about photographers who, through documentation of difficult moments can teach us a lot about human history and about intolerance, about injustice. There's a lot of lessons we can learn through conflict photography that feel important to me.

Govenar: Do you think that the exhibitions of this kind force people to confront issues of truth? Of what really happened?

Gresh: I hope that it forces people to at least look for truth, right? Now, do they face the truth is a more complex question, because there are so many different truths. And where does the truth lie? I don't know, but I hope it inspires people to question the truth, to question reality, and also to become aware of what the reality is, as opposed to ignoring it.

Govenar: Dee, for you, what's your takeaway? You’ve done a lot of different shows of your photographs, and they're above your garage. What do you want people to get from the images?

Mitchell: When there are a hundred people in the house, and maybe a third, or maybe up to half of them go look in the office, they usually, by now, know what sort of thing they’re going to get, or what they're going to see. And some people just can't come out and say, “I just couldn't look at it.” And other people, though, they wanted to know more. I think that may even be the takeaway, that to see these individual photographs of very specific moments, taking place either in the last year or the last ten or twenty years, very far away from where we live, but that we are very, totally invested in as a nation and as a population. People wanting to know more after they've seen these photographs, I think that's the best, the most satisfying response for me.

Gresh: For me, it feels deeply important to bring the world into the museum, to open people's eyes to a lot of things. And I think that conflict photography is a way to raise awareness on the human level, taking out politics entirely, but thinking about injustices in a larger sense. I don't necessarily think of an event and then say, “Oh, well, we need to get that event publicized.” It's more thinking about photographers who, through documentation of difficult moments can teach us a lot about human history and about intolerance, about injustice. There's a lot of lessons we can learn through conflict photography that feel important to me.

Govenar: Do you think that the exhibitions of this kind force people to confront issues of truth? Of what really happened?

Gresh: I hope that it forces people to at least look for truth, right? Now, do they face the truth is a more complex question, because there are so many different truths. And where does the truth lie? I don't know, but I hope it inspires people to question the truth, to question reality, and also to become aware of what the reality is, as opposed to ignoring it.

Govenar: Dee, for you, what's your takeaway? You’ve done a lot of different shows of your photographs, and they're above your garage. What do you want people to get from the images?

Mitchell: When there are a hundred people in the house, and maybe a third, or maybe up to half of them go look in the office, they usually, by now, know what sort of thing they’re going to get, or what they're going to see. And some people just can't come out and say, “I just couldn't look at it.” And other people, though, they wanted to know more. I think that may even be the takeaway, that to see these individual photographs of very specific moments, taking place either in the last year or the last ten or twenty years, very far away from where we live, but that we are very, totally invested in as a nation and as a population. People wanting to know more after they've seen these photographs, I think that's the best, the most satisfying response for me.

Following an inflammatory speech by President Trump, protestors objecting to the certification of Joe Biden by Congress storm the Capitol. They were briefly blocked by police before gaining entry, and wreaked havoc before being expelled with few arrests. One protestor was shot and killed. Washington, D.C., January 6, 2021. © Peter van Agtmael / Magnum Photos

|

|

Delve deeper“Guest Blog: Capturing Today's Wars in Photos,” Charles Dee Mitchell, Art & Seek, April 14, 2011

|