|

|

About the PhotographerNanna Heitmann is a German/Russian documentary photographer, based between Russia and Germany. Her work has been published by TIME magazine, M Le Magazine du Monde, De Volkskrant, die Zeit, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Stern Magazine. She has received awards and accolades that include the Vogue Italia Prize at the PH Museum women photographers grant, World Report Award, and she was shortlisted by the Gomma Grant and LensCulture emerging talents. Heitmann joined Magnum as a nominee in 2019. |

|

Alan Govenar: Could you finish the sentence “Truth in photography is…”

Nanna Heitmann: I think truth in photography doesn’t exist or it’s always subjective. Maybe truth in photography is my perspective on how I view things.

Govenar: What started you doing your work on Covid-19?

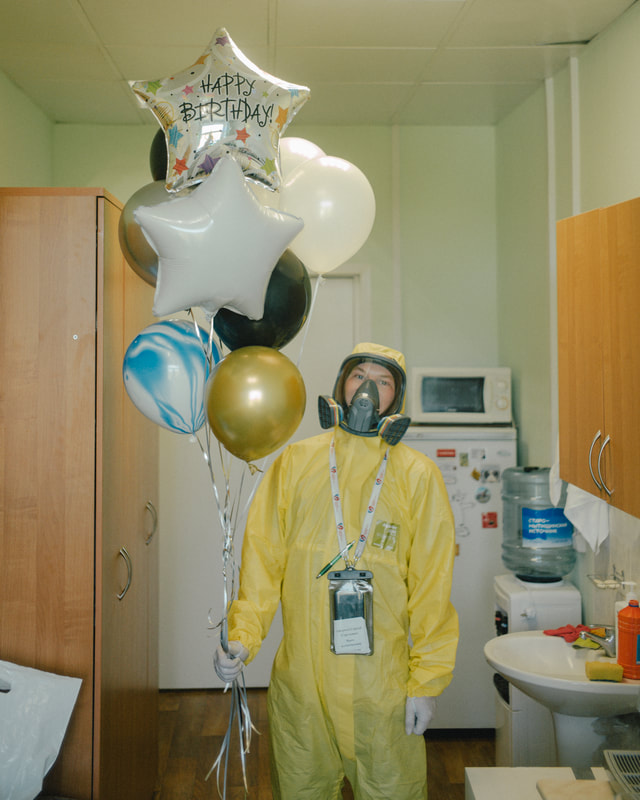

Heitmann: When the lockdown in Moscow started, or generally the lockdown worldwide, there were conversations among the Magnum photographers where every photographer was thinking how to have their own voice represented in such a historic moment, as well as how to photograph something which is invisible. Everyone was writing their thoughts about the pandemic, how to photograph generally how their life is, and I think this was really inspiring or motivating for me to read the words of all those photographers, and later see results from photographers like Alex Majoli, who photographed in Italy.

Nanna Heitmann: I think truth in photography doesn’t exist or it’s always subjective. Maybe truth in photography is my perspective on how I view things.

Govenar: What started you doing your work on Covid-19?

Heitmann: When the lockdown in Moscow started, or generally the lockdown worldwide, there were conversations among the Magnum photographers where every photographer was thinking how to have their own voice represented in such a historic moment, as well as how to photograph something which is invisible. Everyone was writing their thoughts about the pandemic, how to photograph generally how their life is, and I think this was really inspiring or motivating for me to read the words of all those photographers, and later see results from photographers like Alex Majoli, who photographed in Italy.

Photographs by Alex Majoli. © Alex Majoli / Magnum Photos

Govenar: So during what period did you make those photographs?

Heitmann: I started to photograph in April [2020]. The first time I was in the hospital itself was the end of April, but before that I was photographing the Easter ceremonies of the Orthodox Church. What fascinated me also in the pandemic was making so many pictures I thought I’d seen before in the 1918 flu. I saw pictures of crowded people standing in front of a church in New York, I think. So many motifs I’ve seen one hundred years ago, and now they’re coming back. The Orthodox Church was not acknowledging that there’s this virus, or denying its existence, so the Easter processions would continue.

Heitmann: I started to photograph in April [2020]. The first time I was in the hospital itself was the end of April, but before that I was photographing the Easter ceremonies of the Orthodox Church. What fascinated me also in the pandemic was making so many pictures I thought I’d seen before in the 1918 flu. I saw pictures of crowded people standing in front of a church in New York, I think. So many motifs I’ve seen one hundred years ago, and now they’re coming back. The Orthodox Church was not acknowledging that there’s this virus, or denying its existence, so the Easter processions would continue.

Govenar: In those photographs, they have a coloration that is really amazing to me. There’s something about the compositions that remind me of the paintings of Bruegel. Did you think that when you were photographing?

Heitmann: In Russia, the church services didn’t take place, or just illegally, so I drove to a city which is two hours away from Moscow. There, I was going from church to church and asking before the service starts for permission, and most churches didn’t want me to photograph. In the end, I could photograph at this church, and it also ended up being this really old church with candles, and it kind of really reminded me of being in some other time. Except the masks. I decided to take the picture from the corner where there was this construction work and people sitting, because usually in an Orthodox Church service, it starts somewhere in the late evening and lasts until sunrise, until five o’clock in the morning. And usually people are always standing all this time. Only the old and the children, they had some benches in the back. I found this was the most meaningful place.

Heitmann: In Russia, the church services didn’t take place, or just illegally, so I drove to a city which is two hours away from Moscow. There, I was going from church to church and asking before the service starts for permission, and most churches didn’t want me to photograph. In the end, I could photograph at this church, and it also ended up being this really old church with candles, and it kind of really reminded me of being in some other time. Except the masks. I decided to take the picture from the corner where there was this construction work and people sitting, because usually in an Orthodox Church service, it starts somewhere in the late evening and lasts until sunrise, until five o’clock in the morning. And usually people are always standing all this time. Only the old and the children, they had some benches in the back. I found this was the most meaningful place.

Govenar: When you’re making these photographs, what’s going on in your mind? Are you just responding spontaneously? Do you have some sense of what you’re trying to do, what you’re trying to say through your photographs?

Heitmann: I think it’s always mixed. Sometimes I try to prepare. And I also like a lot of historic art, and how the Flemish masters worked with light. In this case, it was important for me to show how there’s such a denying of the existence of the virus, and the most vulnerable people are just packed up in this building to stay all the night.

Govenar: That life goes on regardless.

Heitmann: Regardless of everything, people are singing. Nuns were singing like angels. I was there with my partner, and he fell asleep, and at some point he said he had the feeling like there were angels.

Govenar: It’s interesting that you mention Flemish painting because they seem compositionally to be influenced by painting. Did you think about this when you were making them?

Heitmann: Maybe unconsciously. I don’t know. I really like the Flemish art and I look at it a lot. So maybe unconsciously I get reminded.

Heitmann: I think it’s always mixed. Sometimes I try to prepare. And I also like a lot of historic art, and how the Flemish masters worked with light. In this case, it was important for me to show how there’s such a denying of the existence of the virus, and the most vulnerable people are just packed up in this building to stay all the night.

Govenar: That life goes on regardless.

Heitmann: Regardless of everything, people are singing. Nuns were singing like angels. I was there with my partner, and he fell asleep, and at some point he said he had the feeling like there were angels.

Govenar: It’s interesting that you mention Flemish painting because they seem compositionally to be influenced by painting. Did you think about this when you were making them?

Heitmann: Maybe unconsciously. I don’t know. I really like the Flemish art and I look at it a lot. So maybe unconsciously I get reminded.

Govenar: Photographing people in the hospital raises different kinds of ethical questions. People are suffering, people are working. To what extent do you think about these ethical questions when you’re photographing people?

|

Heitmann: (reply in video)

|

|

|

Govenar: When you document this world, what do you hope the viewer of your photographs gets from them?

Heitmann: The first time I was in the hospital, I was terrified to see all the patients and also patients my age. I met one war photographer, Uri Kasura. I was thinking, “What am I doing here?” This guy has seen so many wars and has been to so many conflict zones, he can go through there so relaxed and so focused and photograph everything, and I was wondering what am I doing there. I wasn’t really able to raise my camera the first day. At this time, I was in really close contact to the Russian editor. He worked also previously as an editor for Time magazine. I told him, “I met Uri, and I think he can do this so much better than I’m doing it.” And later, when he saw the pictures, I think he was saying that, especially because I’m not this typical war photographer, I could show a totally different perspective, or maybe a more gentle view on what is happening. |

Govenar: When you’re talking about this idea of being more gentle, it’s your presence, it’s your body language. So when you’re talking about these photographs in the hospital and trying to give a more gentle view, it’s because that’s what you’re emanating to the subject, and they’re responding to you. Do you believe that to be true?

Heitmann: Yes, yes, for sure. I think I have to say I was also talking to the women sometimes, especially with the hospital. I sometimes get too much into the person, or I mention myself sometimes too much. So sometimes I have the feeling I would like to be more distanced from the person or her pain. Because I think I’m getting emotionally too close, and it’s kind of really affecting me psychologically.

Heitmann: Yes, yes, for sure. I think I have to say I was also talking to the women sometimes, especially with the hospital. I sometimes get too much into the person, or I mention myself sometimes too much. So sometimes I have the feeling I would like to be more distanced from the person or her pain. Because I think I’m getting emotionally too close, and it’s kind of really affecting me psychologically.

Heitmann: My mom, she’s a psychotherapist, and my dad, he’s an ergo-therapist. He works with people who had a brain stroke, who are paralyzed, to make their life easier. Sometime before I started studying, I was sometimes following him where he works with his patients. I felt so sad for some patients, and I was asking him how he works with them everyday, and he says, “Feeling sad for them doesn’t help anyone, it kind of destroys yourself and it doesn’t help them.” That’s something I was thinking back on so often, but it’s really hard doing.

|

|

Delve deeper |