This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the CuratorDavid Campany is Curator at Large at the International Center of Photography, New York. His books include On Photographs (2020), A Handful of Dust (2015), Art and Photography (2003), Jeff Wall: Picture for Women (2011), Walker Evans: The Magazine Work (2014), and Photography and Cinema (2008). He curated the two current exhibitions, A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload, and Actual Size! Photography at Life Scale, at the International Center of Photography, New York. |

|

Truth in Photography: Tell me about these two exhibitions at the International Center of Photography.

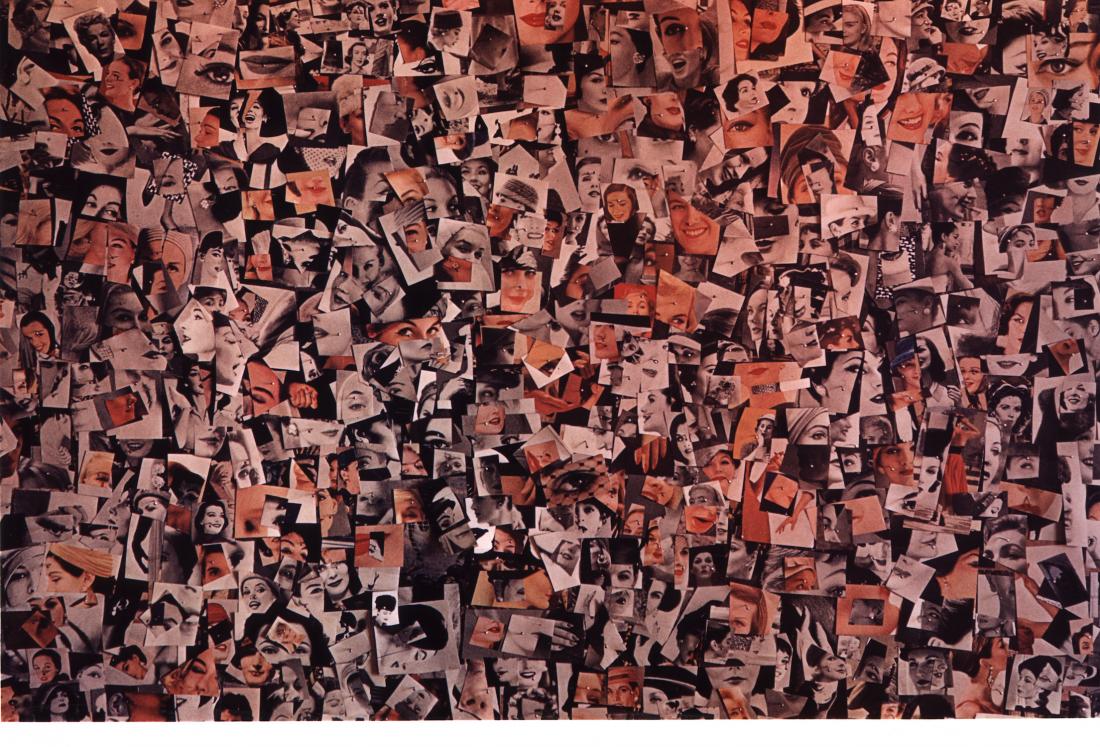

David Campany: A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload takes a very simple idea and puts it into a historical perspective. Pretty much every day somebody tells me that there are too many images in the world. That we are bombarded by them, flooded, or there's an inundation of images. These are words of catastrophe, but they're also words that suggest that we feel images are coming for us, are coming to get us; that they have us in mind, that we are being targeted somehow. That's really a common characteristic of how we feel about the contemporary image world. But in fact, it is a worry, or a fascination, with a long history really, going back to the 1920s with the birth of the modern mass media. After the first World War, there was an enormous explosion in the number of illustrated magazines and newspapers. Suddenly, the amount of photographs that people were seeing went up exponentially, and it's continued that way for the last century. So this is an exhibition that really takes a historical look across the last century, presenting the work of various artists who've worked with existing images. It might be montage, or collage, or appropriation of one kind or another. We have works that are made on paper, works that are in book form, works that are on screens, but they come from every decade of the last century, from the 1920s onwards.

David Campany: A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload takes a very simple idea and puts it into a historical perspective. Pretty much every day somebody tells me that there are too many images in the world. That we are bombarded by them, flooded, or there's an inundation of images. These are words of catastrophe, but they're also words that suggest that we feel images are coming for us, are coming to get us; that they have us in mind, that we are being targeted somehow. That's really a common characteristic of how we feel about the contemporary image world. But in fact, it is a worry, or a fascination, with a long history really, going back to the 1920s with the birth of the modern mass media. After the first World War, there was an enormous explosion in the number of illustrated magazines and newspapers. Suddenly, the amount of photographs that people were seeing went up exponentially, and it's continued that way for the last century. So this is an exhibition that really takes a historical look across the last century, presenting the work of various artists who've worked with existing images. It might be montage, or collage, or appropriation of one kind or another. We have works that are made on paper, works that are in book form, works that are on screens, but they come from every decade of the last century, from the 1920s onwards.

Truth in Photography: How do we know if there are enough images? How do we make sense of all that?

Campany: When we feel there are too many images, I think what we suffer from is a problem of concentration and a problem of focus. It's a feeling of distraction that we are losing something. It might be a sense of truth, or it might be a sense of purpose or place in the world. The images are bewildering us somehow.

TiP: How do we know if an image is true?

Campany: Images don't speak truths, but we measure our experience against images. And maybe that's where the truth is.

TiP: Complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”

Campany: Truth in photography is a moving target, and that's because the world is changing very fast and there's no fixed way to represent it. No fixed way to understand it. One has to experiment in order to represent the world. There are no pre-given forms or conventions. So truth in photography is an experimental business. It's not a matter of a fixed way of depicting things, and it always involves a lot of guesswork, a lot of speculation, a lot of trying things out. If we knew how to be truthful with photography, we would all be doing it. But we don't know.

TiP: Talk about some of the specific images in this exhibition.

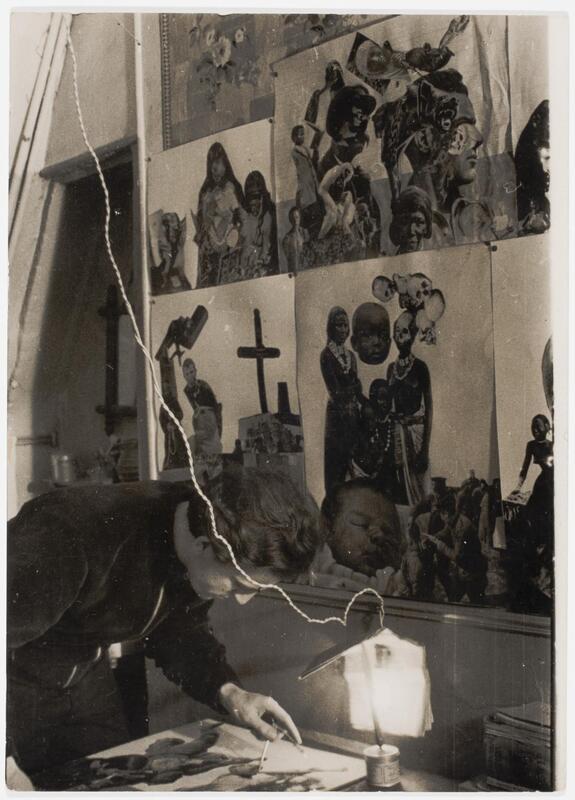

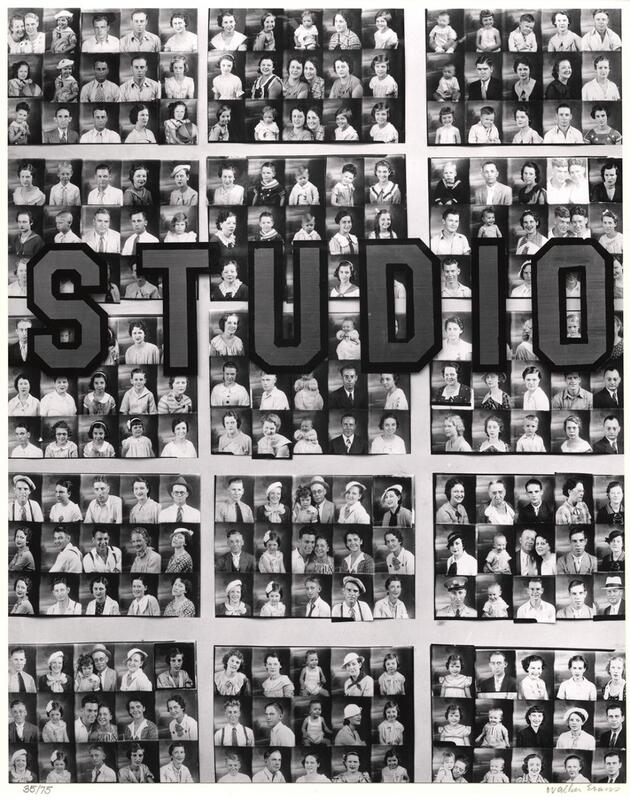

Campany: If you go right back to the 1920s and 30s, you find artists really grappling with the modern image world and this feeling that the number of images is getting out of control. For example, the German artist Hannah Hoch kept media scrapbooks, unpublished albums of images that she would find in popular magazines. This was her way of processing it, of making sense of it psychologically, emotionally, artistically. Around the same time, you have artists like Walker Evans, who understood that the modern world was full of images and that if you wanted to be a photographer in the modern world, you would have to include images within your images rather than avoiding them.

TiP: Talk about the title of the exhibition.

Campany: The exhibition titled A Trillion Sunsets obviously points us towards the most popular kind of image, which is a photograph of a sunset. But of course, a sunset and a photograph of a sunset are two very different things. Everyone finds a sunset beautiful and everyone finds a photograph of a sunset to be a cliché, a kind of cheesecake picture.

TiP: So that's the dilemma.

Campany: It is, it is a dilemma. One feels in the contemporary image world that for every image one is looking at, there are millions out there that one is not looking at, that are somehow waiting for us on hard drives, on screens somewhere else.

TiP: What makes a photograph iconic?

Campany: The more images there are in the world, the more desire there is to invest in single pictures that might summarize things, capture things, hence the iconic picture. But of course, the iconic picture in a way is a distraction, because a single photograph can't really summarize anything particularly complex. But still, there is a desire for a single picture to hold that. At the same time, there are artists that avoid the single picture, that look to the multiplicity of pictures, huge collections of pictures, archives, albums, series, suites, sequences, all the ways of putting images together. And really, that is what typifies the image world that we live in. It's not single images, it's the great number of pictures.

Campany: When we feel there are too many images, I think what we suffer from is a problem of concentration and a problem of focus. It's a feeling of distraction that we are losing something. It might be a sense of truth, or it might be a sense of purpose or place in the world. The images are bewildering us somehow.

TiP: How do we know if an image is true?

Campany: Images don't speak truths, but we measure our experience against images. And maybe that's where the truth is.

TiP: Complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”

Campany: Truth in photography is a moving target, and that's because the world is changing very fast and there's no fixed way to represent it. No fixed way to understand it. One has to experiment in order to represent the world. There are no pre-given forms or conventions. So truth in photography is an experimental business. It's not a matter of a fixed way of depicting things, and it always involves a lot of guesswork, a lot of speculation, a lot of trying things out. If we knew how to be truthful with photography, we would all be doing it. But we don't know.

TiP: Talk about some of the specific images in this exhibition.

Campany: If you go right back to the 1920s and 30s, you find artists really grappling with the modern image world and this feeling that the number of images is getting out of control. For example, the German artist Hannah Hoch kept media scrapbooks, unpublished albums of images that she would find in popular magazines. This was her way of processing it, of making sense of it psychologically, emotionally, artistically. Around the same time, you have artists like Walker Evans, who understood that the modern world was full of images and that if you wanted to be a photographer in the modern world, you would have to include images within your images rather than avoiding them.

TiP: Talk about the title of the exhibition.

Campany: The exhibition titled A Trillion Sunsets obviously points us towards the most popular kind of image, which is a photograph of a sunset. But of course, a sunset and a photograph of a sunset are two very different things. Everyone finds a sunset beautiful and everyone finds a photograph of a sunset to be a cliché, a kind of cheesecake picture.

TiP: So that's the dilemma.

Campany: It is, it is a dilemma. One feels in the contemporary image world that for every image one is looking at, there are millions out there that one is not looking at, that are somehow waiting for us on hard drives, on screens somewhere else.

TiP: What makes a photograph iconic?

Campany: The more images there are in the world, the more desire there is to invest in single pictures that might summarize things, capture things, hence the iconic picture. But of course, the iconic picture in a way is a distraction, because a single photograph can't really summarize anything particularly complex. But still, there is a desire for a single picture to hold that. At the same time, there are artists that avoid the single picture, that look to the multiplicity of pictures, huge collections of pictures, archives, albums, series, suites, sequences, all the ways of putting images together. And really, that is what typifies the image world that we live in. It's not single images, it's the great number of pictures.

TiP: It's hard not to talk about January 6th in terms of the thousands of images. If we keep seeing these images, are they making us numb to their content?

Campany: We often hear it said that images make us numb to the content if we see too many images, that we are no longer able to respond either intellectually or emotionally. But maybe that feeling is self-defense. If we tell ourselves we feel numb, then we feel numb. But maybe the excess doesn't have anything to do with the number. Maybe the feeling of excess is the fact that any photograph can have many meanings. It can be very ambiguous. Maybe the problem of excess exists in every photograph. Any given image has too much information, too much ambiguity, too much possibility. Perhaps it's nothing to do with the number, nothing to do with the volume of images.

TiP: Why should a photograph of a real situation be any less artistic than one that's a fictional reality?

Campany: I think every photograph is both a document and an interpretation. If it's an interpretation, it's also potentially an artwork. Where the emphasis falls really depends on what we want from the image and how it's used. The interesting thing about photographs is they are so dependent on their context, how they’re used, who's using them, who wants what meanings from them. And that tells us more about us and what we'd like from photographs, than it actually tells us about the photographs themselves.

It's a bit like that diagram of a cube that you look at, and sometimes you can see the cube one way, sometimes you can see the cube the other way, but you can never have them both at the same time. The document character of the photograph and the art character of the photograph are a little bit like that. They never quite add up, they never quite reconcile. But they're both there, and they're both potentials of every image. Oscar Wilde once said that if you give a person a mask, they will give you their truth. And I think photography has an interesting relation to that. You can go into the world and try and photograph the actuality of the world and arrive at some kind of truth. You can also go into the studio and construct an entirely fictional world that might get you close to another kind of truth.

Campany: We often hear it said that images make us numb to the content if we see too many images, that we are no longer able to respond either intellectually or emotionally. But maybe that feeling is self-defense. If we tell ourselves we feel numb, then we feel numb. But maybe the excess doesn't have anything to do with the number. Maybe the feeling of excess is the fact that any photograph can have many meanings. It can be very ambiguous. Maybe the problem of excess exists in every photograph. Any given image has too much information, too much ambiguity, too much possibility. Perhaps it's nothing to do with the number, nothing to do with the volume of images.

TiP: Why should a photograph of a real situation be any less artistic than one that's a fictional reality?

Campany: I think every photograph is both a document and an interpretation. If it's an interpretation, it's also potentially an artwork. Where the emphasis falls really depends on what we want from the image and how it's used. The interesting thing about photographs is they are so dependent on their context, how they’re used, who's using them, who wants what meanings from them. And that tells us more about us and what we'd like from photographs, than it actually tells us about the photographs themselves.

It's a bit like that diagram of a cube that you look at, and sometimes you can see the cube one way, sometimes you can see the cube the other way, but you can never have them both at the same time. The document character of the photograph and the art character of the photograph are a little bit like that. They never quite add up, they never quite reconcile. But they're both there, and they're both potentials of every image. Oscar Wilde once said that if you give a person a mask, they will give you their truth. And I think photography has an interesting relation to that. You can go into the world and try and photograph the actuality of the world and arrive at some kind of truth. You can also go into the studio and construct an entirely fictional world that might get you close to another kind of truth.

TiP: Talk about the other exhibition.

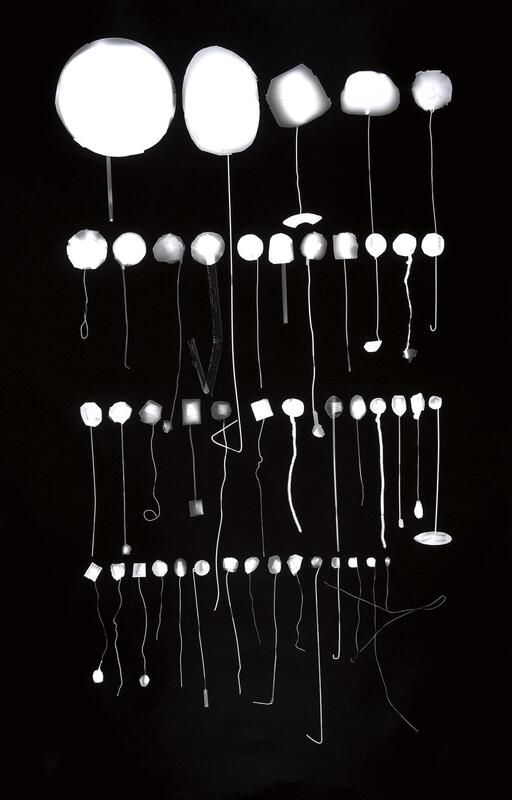

Campany: We are also presenting an exhibition titled, Actual Size! Photography at Life Scale. The question of scale in photography is really fascinating because, of course, a photograph can be any size. When we see photographs, we don't think about scale very much. We might see a photograph on a fridge magnet, a poster, a screen, a framed print on a wall, a billboard, and we never really question its size. We accept it at whatever size it is. And there's something essentially elastic about photography, and that's because what happens with photography is you capture an image, press the shutter, and then there's output. It's always a two-stage process. And you can output an image in a number of different ways. So whenever you're looking at a photograph, a photographic output, you know it could also be a hundred other ways. But there's a particular phenomenon that happens when you look at a photograph that is actual size, one-to-one scale. What does it mean to look at a photograph which is the same size as its subject matter? In the exhibition, you will see an image of a Greyhound bus, which is the size of a Greyhound bus. You will see an image of Muhammad Ali's fist, which is the same size as Muhammad Ali's fist. You'll see the floor of a forest represented at the same size as that forest floor. The subject matter varies wildly from image to image but they all share the same scale as each other, which is the same bodily scale as the viewer.

Campany: We are also presenting an exhibition titled, Actual Size! Photography at Life Scale. The question of scale in photography is really fascinating because, of course, a photograph can be any size. When we see photographs, we don't think about scale very much. We might see a photograph on a fridge magnet, a poster, a screen, a framed print on a wall, a billboard, and we never really question its size. We accept it at whatever size it is. And there's something essentially elastic about photography, and that's because what happens with photography is you capture an image, press the shutter, and then there's output. It's always a two-stage process. And you can output an image in a number of different ways. So whenever you're looking at a photograph, a photographic output, you know it could also be a hundred other ways. But there's a particular phenomenon that happens when you look at a photograph that is actual size, one-to-one scale. What does it mean to look at a photograph which is the same size as its subject matter? In the exhibition, you will see an image of a Greyhound bus, which is the size of a Greyhound bus. You will see an image of Muhammad Ali's fist, which is the same size as Muhammad Ali's fist. You'll see the floor of a forest represented at the same size as that forest floor. The subject matter varies wildly from image to image but they all share the same scale as each other, which is the same bodily scale as the viewer.

|

TiP: The same scale as reality. What does that do to perception?

Campany: Most of the time, when we look at photographs, they're representing things smaller than they really are. Occasionally, they're bigger, and we are used to that flexibility. But a photograph that is the same size as what it's of, one-to-one, produces a very special kind of response in the viewer, and in a way that's the truest calling of photography, which is to be some kind of direct substitute for the world. But the directness is also disarming, and a little uncanny. When you're looking at an image of something that is the same size as what it’s of, it's a very real experience, but it's also a very virtual one. You know you're not in front of that person or that object, but you're looking at a life scale representation of them. They can't look back at you. You can't engage with them, and yet you're there in the presence of a full-size spectre. TiP: Talk about these images in relationship to issues of truth or fiction. Campany: Maybe one of the biggest untruths about photography is scale. If you look at your passport, the biggest untruth is the fact that you're very small in that picture. We think of a passport photo as being a very true kind of picture, but it has miniaturized you. Of course, nobody wants a passport the same size as your face. So most of the time, images are smaller for practical reasons. But the actual size photograph, the one-to-one photograph, has been attractive in all kind of way to artists, to documentary photographers, to advertisers. For example, for a large part of the 20th century, advertisers liked to present their goods, their wares, at actual size. Many magazine adverts for cameras, for example, or even handguns, would reproduce them actual size on the page. So, you could imagine reaching out, taking hold of them the objects, pulling them into your life. That's a very special and unusual scale. |

|

|

|