|

|

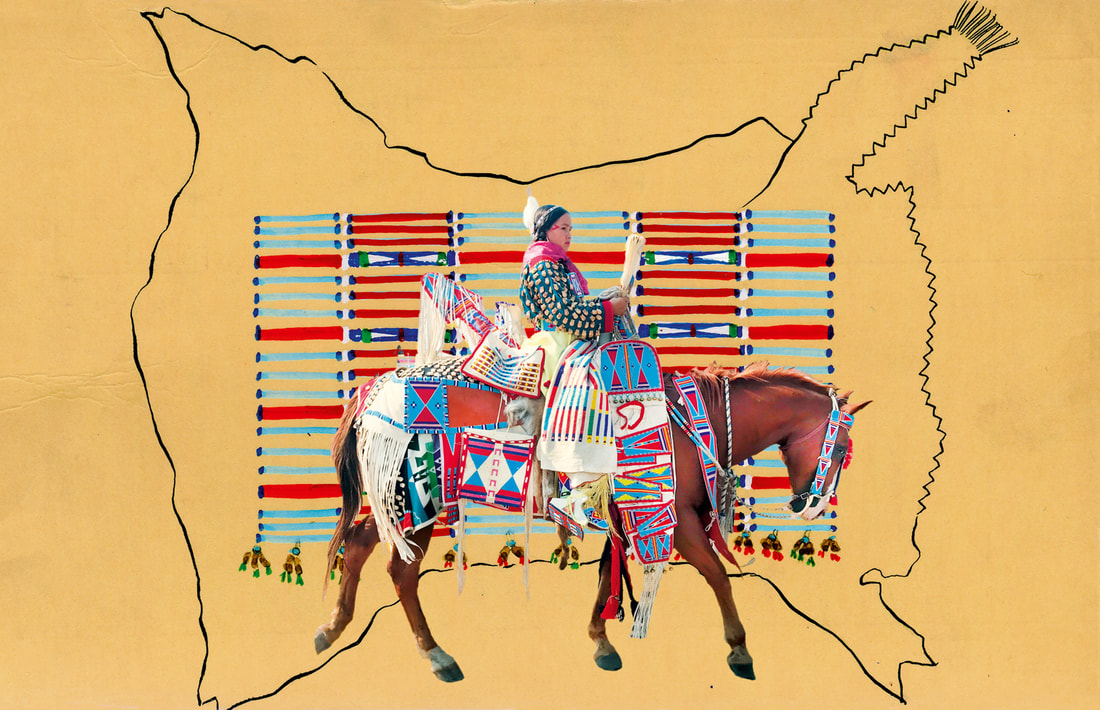

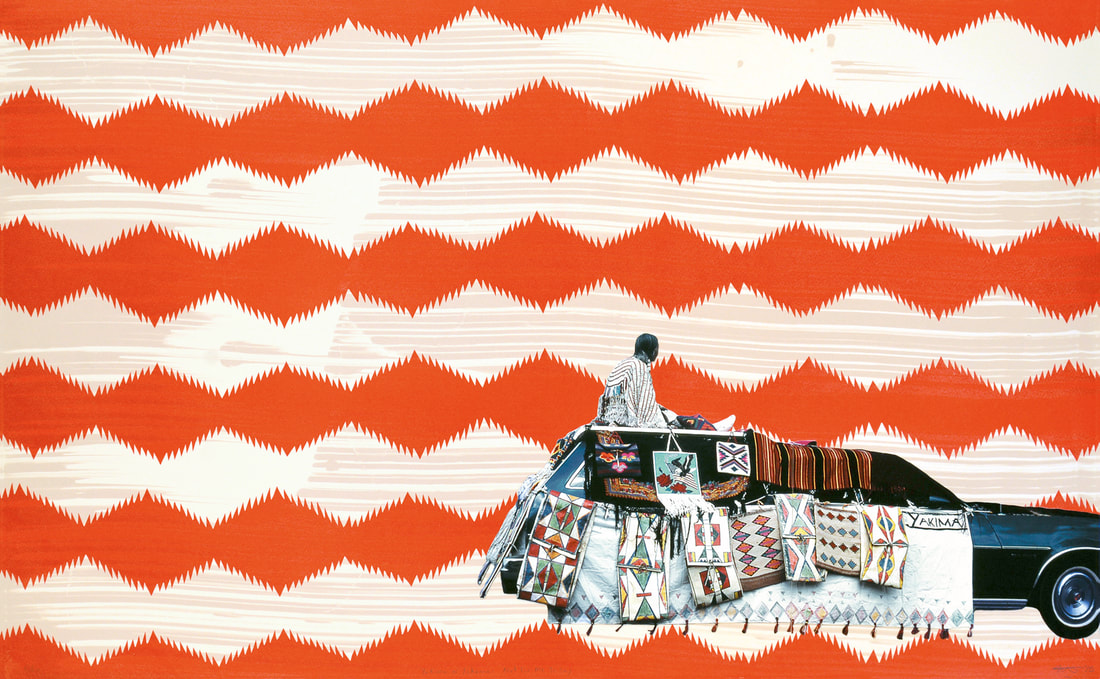

About the ArtistRaised on the Apsáalooke (Crow) reservation in Montana, Wendy Red Star’s work is informed both by her cultural heritage and her engagement with many forms of creative expression, including photography, sculpture, video, fiber arts, and performance. An avid researcher of archives and historical narratives, Red Star seeks to incorporate and recast her research, offering new and unexpected perspectives in work that is at once inquisitive, witty and unsettling. Red Star holds a BFA from Montana State University, Bozeman, and an MFA in sculpture from University of California, Los Angeles. She lives and works in Portland, OR. Her first monograph Wendy Red Star: Delegation is being published by Aperture. |

|

TiP: Could you speak about how you became a photographer—and how you felt the imagery you saw of Native American people like yourself was not really representing who you are?

Red Star: I've always been invested in photography without really fully understanding that until much later in my practice. Beginning as an undergrad, I was drawn to seeing historical images. One of the things that the window of photography has opened up for me, especially when I've left the reservation, is a sense of having my community around. When I'm seeing these historical photos and have an opportunity to see who the subjects are in the photo, they feel like family to me. There are all these things that I'm seeing within the photo that I really want to kind of bring out, and explode that image open, so people get that sense of my experience of looking.

TiP: Now that you've made your first monograph, has it been a lot to process in terms of the way in which you want to shape the narrative of your work across fifteen years?

Red Star: It is a lot to process. My education is in three-dimensional sculpture. It wasn't until graduate school that I was around a bunch of photographers and I really became interested in photography as a medium beyond documentation. My book focuses primarily on my use of photography in other applications such as collage and multimedia, and so I feel like I kind of have this outsider's perspective in the photography world. An adjacent perspective to it. So it's been really wonderful to work with Aperture, and to navigate my photo work, to pull things that I might not see as relevant, and to have their guiding hand in that. I also realized, wow, I have a lot of images to work from. I was sort of worried about that, putting together such a substantial book and not having enough work. But I'm finding that not to be the case. In the end, I actually had to edit some things out.

TiP: Could you describe the process of selection?

Red Star: In the beginning, for me, this is a lot about finding my own place and my own identity, especially an identity outside of my community, but also staying connected to my culture and where I come from. So there's this self-portraiture that has a strong arc in it, and then it's shifted out to research focused projects that delve into the histories of the Apsáalooke nation and the US government and work with a lot of historical photographs and museum collections of Apsáalooke material objects. I basically want to know how I got here, through the work that I'm doing and the histories that I'm uncovering. The work that will be in this book will tie a bunch of these timelines that I've been working on for years, will complete and fill those gaps in.

Red Star: I've always been invested in photography without really fully understanding that until much later in my practice. Beginning as an undergrad, I was drawn to seeing historical images. One of the things that the window of photography has opened up for me, especially when I've left the reservation, is a sense of having my community around. When I'm seeing these historical photos and have an opportunity to see who the subjects are in the photo, they feel like family to me. There are all these things that I'm seeing within the photo that I really want to kind of bring out, and explode that image open, so people get that sense of my experience of looking.

TiP: Now that you've made your first monograph, has it been a lot to process in terms of the way in which you want to shape the narrative of your work across fifteen years?

Red Star: It is a lot to process. My education is in three-dimensional sculpture. It wasn't until graduate school that I was around a bunch of photographers and I really became interested in photography as a medium beyond documentation. My book focuses primarily on my use of photography in other applications such as collage and multimedia, and so I feel like I kind of have this outsider's perspective in the photography world. An adjacent perspective to it. So it's been really wonderful to work with Aperture, and to navigate my photo work, to pull things that I might not see as relevant, and to have their guiding hand in that. I also realized, wow, I have a lot of images to work from. I was sort of worried about that, putting together such a substantial book and not having enough work. But I'm finding that not to be the case. In the end, I actually had to edit some things out.

TiP: Could you describe the process of selection?

Red Star: In the beginning, for me, this is a lot about finding my own place and my own identity, especially an identity outside of my community, but also staying connected to my culture and where I come from. So there's this self-portraiture that has a strong arc in it, and then it's shifted out to research focused projects that delve into the histories of the Apsáalooke nation and the US government and work with a lot of historical photographs and museum collections of Apsáalooke material objects. I basically want to know how I got here, through the work that I'm doing and the histories that I'm uncovering. The work that will be in this book will tie a bunch of these timelines that I've been working on for years, will complete and fill those gaps in.

|

TiP: The connection you feel with the ancestors, is that a spiritual relationship?

Red Star: It is. I almost feel like they're working through me, because of the incredible things that happened. For instance, I did a Smithsonian Research Artist Fellowship, and I worked in the collections of the National Museum of American Indian and the National Anthropological Archives. Immediately, when I started looking at these historical images, there were ancestral connections with them and photographs of my great-great-grandparents. And actually, within the material objects, there were over a hundred objects that were related to my biological family. It just seemed like they were revealing themselves. That was a very powerful thing to experience. The work that I'm doing has a lot of purpose beyond just my own personal interests. It really is for the future generations. I’m really hoping that they can use my work as a starting place, that they don't have to work as hard to gather things together, because I'm trying to do that for them. TiP: In terms of this relationship between the ancestors, the objects, and the artifacts that you found, how does that impact your approach to self-portraiture? Red Star: Each of those discoveries tells me more about who I am. Finding out about my ancestors and reading what they were going through, who the photographer was who photographed them, and why they were photographing them at that time period. What was their agenda? You fast forward all of that, and it leads me to the experience that I had as a kid growing up on the Crow reservation, hearing my dad talk about land allotments and understanding, “Oh, this comes from this ancestor. We were related this way and that's why I'm here standing on this piece of land.” It informs me and I feel deeply rooted and centered through the work that I do. |

TiP: How does it impact your image making in terms of photography?

Red Star: Having that sculpture background, for me to make photo makes sense—I have to make it feel like an object or make it three-dimensional in itself. For instance, I did a project at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, where I worked with a historical photographer named Frank Rhinehart, who photographed the Trans Mississippi Exposition that happened in 1898. And as part of that exposition, there was an Indian Congress where they brought in over 30 different tribes, and one of those tribes was Crow, my tribe. He took studio portraits and full portraits of the different native delegations. For me to make sense of that event, I wanted to feel it, and the way to feel it was to sort of recreate what that would be. There were about five hundred native people there. And I just thought, “How incredible would that have been to have these different tribal nations all gathered there and to walk amongst the native people?” So, the way that I recreated that was to cut out all of the people in the portraits and reconstruct the gathering so that the viewer could walk through and feel what that would be like and to meet each of these individuals free of their composed backdrop.

TiP: You're trying to superimpose the three-dimensional into this two-dimensional medium.

Red Star: Exactly. When I was in graduate school at UCLA, in my sculpture program I created diorama backdrops, and I, myself, was in the diorama, and then the scene was photographed for documentation. It took me a while to realize, “No, actually, this is a photo,” but there is a little bit of that sort of separation there, in the beginning. But now I've learned that’s just the way that I work and that's how the photo makes sense to me.

TiP: How does focus work for you? Do you want everything in focus, or are you trying to establish the spatial relationship you get from shallow focus or soft focus?

Red Star: Because I don't actually have any formal training in photo, I'm just trying to make it work. A great example is the work that I did with my daughter, Beatrice. We did a portrait together on a couch with a dazzling background. And we were both in our traditional dresses. And that was self-timer, really praying, hoping that it worked. And actually, the remote was broken, so I'd have to run in between takes and hit the button and I'm jumping on the couch. I had no idea what Beatrice was even doing, how she was posing. And somehow we were able to pull four really great photos. In that case I wanted us to be the sharp focus and through manipulation with Photoshop, the background is all blurred, but it feels very haphazard. My way of photographing is very haphazard and not technical at all. It's almost embarrassing, but somehow that equation, it works for me.

Red Star: Having that sculpture background, for me to make photo makes sense—I have to make it feel like an object or make it three-dimensional in itself. For instance, I did a project at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, where I worked with a historical photographer named Frank Rhinehart, who photographed the Trans Mississippi Exposition that happened in 1898. And as part of that exposition, there was an Indian Congress where they brought in over 30 different tribes, and one of those tribes was Crow, my tribe. He took studio portraits and full portraits of the different native delegations. For me to make sense of that event, I wanted to feel it, and the way to feel it was to sort of recreate what that would be. There were about five hundred native people there. And I just thought, “How incredible would that have been to have these different tribal nations all gathered there and to walk amongst the native people?” So, the way that I recreated that was to cut out all of the people in the portraits and reconstruct the gathering so that the viewer could walk through and feel what that would be like and to meet each of these individuals free of their composed backdrop.

TiP: You're trying to superimpose the three-dimensional into this two-dimensional medium.

Red Star: Exactly. When I was in graduate school at UCLA, in my sculpture program I created diorama backdrops, and I, myself, was in the diorama, and then the scene was photographed for documentation. It took me a while to realize, “No, actually, this is a photo,” but there is a little bit of that sort of separation there, in the beginning. But now I've learned that’s just the way that I work and that's how the photo makes sense to me.

TiP: How does focus work for you? Do you want everything in focus, or are you trying to establish the spatial relationship you get from shallow focus or soft focus?

Red Star: Because I don't actually have any formal training in photo, I'm just trying to make it work. A great example is the work that I did with my daughter, Beatrice. We did a portrait together on a couch with a dazzling background. And we were both in our traditional dresses. And that was self-timer, really praying, hoping that it worked. And actually, the remote was broken, so I'd have to run in between takes and hit the button and I'm jumping on the couch. I had no idea what Beatrice was even doing, how she was posing. And somehow we were able to pull four really great photos. In that case I wanted us to be the sharp focus and through manipulation with Photoshop, the background is all blurred, but it feels very haphazard. My way of photographing is very haphazard and not technical at all. It's almost embarrassing, but somehow that equation, it works for me.

TiP: I think that some tech training is good, but sometimes it stifles your ability to move forward, and sometimes the way we respond to the world visually in an intuitive sense is different. Do you feel your photographs are intuitive in that way?

Red Star: Definitely. I think culturally, the way that I grew up and the way that I was taught, especially around my Crow family, growing up on the reservation, no one ever sat me down and said, this is how you do this, A to B. No one ever did that. You were supposed to absorb and watch and pick it up. From having that sort of structured learning style, culturally, I tend to approach things that way. And it's not Western at all, where there's instructions and steps and things like that. Thinking about the technical aspects can really bog me down. Having that free form and intuitive way of working is also exciting because there are so many unknowns within it that I really enjoy.

TiP: In making your book, did you have a sense of the beginning, middle, and end? How does it evolve?

Red Star: We wanted to stay away from chronological. We all agreed on that. The designer that I'm working with is very intuitive in working with my images. What I told Brendan was that I really wanted to make this book into an object. That's my way of making sense of it. We’re pairing different images together in interesting ways. There's a lot of texture. There's a lot of color saturation. Every time when you're flipping through the pages, I want it to be a very visual, tactile experience. So, there isn't really a beginning, middle, or end, it's just going to be kind of an epic journey. I don't really want there to be an end.

TiP: Do you want someone going through the book to go through page by page or do you want them to thumb through?

Red Star: I think they could definitely thumb through. They don't have to go page by page. There’s an interview that I do with Josh T. Franco, who's the National Collector at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, which gives the reader background into my life and practice. There are touchstones of different essays and even poetry in there that people can pick up on, but they don't have to go page by page.

TiP: It sounds like you are constantly making things.

Red Star: I actually wish I was making more. To leave these things behind, if you were to die or when you die, it's a really wonderful thing. My grandma, she was a big-time maker of regalia and she would make Crow dolls. I actually found one of her dolls on eBay. And she had passed five years before. I didn't even have to read the description, I just knew it was hers, and I bought it. Then it came to me in the mail. It had been on the East Coast since the ’80s, this doll, and it just really made me love her and love art. That really kind of came into focus for me, the importance of art and in having it for the future generations.

TiP: When people are done looking at your book, do you have a sense of how you want them to feel?

Red Star: I really want them to feel like it is an artwork in itself, and they can keep coming back to it and see new things. It’s so important for me in the work that I make, that it's an entry point, and there's space in there for the viewer to ask questions and then to investigate.

TiP: What are the truths that come through in your work?

Red Star: I'm trying to talk about historical references and stories, and I'm trying to open that up. It's coming through my perspective, so there's my lens on it. The lens that is also so important is the viewer when they come in. What I'm hoping to do is just open these doors onto stories that you might not have been aware of, but that connect us across time and experience.

Red Star: Definitely. I think culturally, the way that I grew up and the way that I was taught, especially around my Crow family, growing up on the reservation, no one ever sat me down and said, this is how you do this, A to B. No one ever did that. You were supposed to absorb and watch and pick it up. From having that sort of structured learning style, culturally, I tend to approach things that way. And it's not Western at all, where there's instructions and steps and things like that. Thinking about the technical aspects can really bog me down. Having that free form and intuitive way of working is also exciting because there are so many unknowns within it that I really enjoy.

TiP: In making your book, did you have a sense of the beginning, middle, and end? How does it evolve?

Red Star: We wanted to stay away from chronological. We all agreed on that. The designer that I'm working with is very intuitive in working with my images. What I told Brendan was that I really wanted to make this book into an object. That's my way of making sense of it. We’re pairing different images together in interesting ways. There's a lot of texture. There's a lot of color saturation. Every time when you're flipping through the pages, I want it to be a very visual, tactile experience. So, there isn't really a beginning, middle, or end, it's just going to be kind of an epic journey. I don't really want there to be an end.

TiP: Do you want someone going through the book to go through page by page or do you want them to thumb through?

Red Star: I think they could definitely thumb through. They don't have to go page by page. There’s an interview that I do with Josh T. Franco, who's the National Collector at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, which gives the reader background into my life and practice. There are touchstones of different essays and even poetry in there that people can pick up on, but they don't have to go page by page.

TiP: It sounds like you are constantly making things.

Red Star: I actually wish I was making more. To leave these things behind, if you were to die or when you die, it's a really wonderful thing. My grandma, she was a big-time maker of regalia and she would make Crow dolls. I actually found one of her dolls on eBay. And she had passed five years before. I didn't even have to read the description, I just knew it was hers, and I bought it. Then it came to me in the mail. It had been on the East Coast since the ’80s, this doll, and it just really made me love her and love art. That really kind of came into focus for me, the importance of art and in having it for the future generations.

TiP: When people are done looking at your book, do you have a sense of how you want them to feel?

Red Star: I really want them to feel like it is an artwork in itself, and they can keep coming back to it and see new things. It’s so important for me in the work that I make, that it's an entry point, and there's space in there for the viewer to ask questions and then to investigate.

TiP: What are the truths that come through in your work?

Red Star: I'm trying to talk about historical references and stories, and I'm trying to open that up. It's coming through my perspective, so there's my lens on it. The lens that is also so important is the viewer when they come in. What I'm hoping to do is just open these doors onto stories that you might not have been aware of, but that connect us across time and experience.

|

|

|