|

|

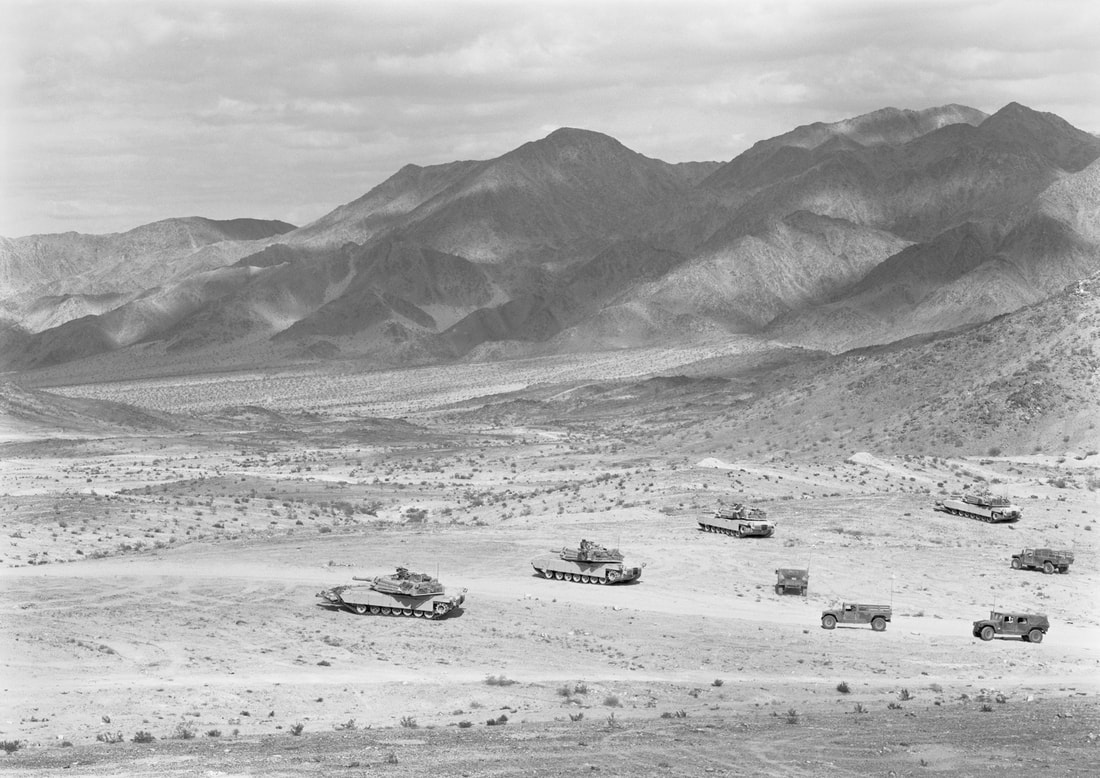

About the PhotographerAn-My Lê was born in Saigon, Vietnam. She has her MFA from Yale School of Art. In 2012, she received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. She lives and works in Brooklyn, New York and is a Professor of Photography at Bard College. |

|

Noncombatant Evacuation Operations Marine Corps Training Area, Bellows Air Force Station, Waimānalo, Hawaii, 2012 (Diptych),

from the series Events Ashore. © An-My Lê

from the series Events Ashore. © An-My Lê

Truth in Photography: What is truth in photography to you?

An My Lê: I first heard when I was in graduate school studying with Todd Papageorge and Richard Benson, that all photography’s fiction. At first I struggled to come to terms with that, because you connect photography, at least the photography that I love with this idea of going out into the real world. It’s about discovering and photographing something about the real world. There is a dichotomy. But Richard had often talked about how photography produces images that are stunning in their depiction of reality because the lenses used to make pictures are close relatives of the organic lenses that provide us with eyesight. It is no wonder that pictures made this way look so much like the world we see. But he went on to say that a difficult side effect of this similarity is that viewers of photographs almost always confuse the pictures with some idea of truth about the world."

I think that what photography does, and it all depends on who has the hand, is creating relationships, is to give more importance to certain things than other things, is to create tensions, to create ambiguity and set the stage for potentials for interpretation. In that sense, it's all fictional and it's all constructed by the maker.

TiP: I think it is a complicated subject, that it is something that we live, particularly in today's world, where there is this great denial of truth in image making. For me, truth is subjective. It's personal, it’s perception. It's a feeling. It's intangible.

Lê: I think it's obvious that I'm not a photojournalist. I do believe in facts. I was trained as a scientist. So, for me, the notion of truth is very subjective, just like it is for you, but I believe in the facts. And I want to see the facts and the facts will help me decide.

I think there's quite a strong structure that is factual in photography. It has to do with the light. It has to do with the details and how things are described again. There's no artist who would not take advantage of this notion of truth, the subjectivity of truth, because there's no ethical code for us. When I did a short story for The New York Times last year, it was always, “Was this Photoshopped? Was this added, or is there anything that was manipulated?” So I think there's a code of ethics that photojournalists have to follow. And I don't. And I think there's a long story that I've told at various times that is relevant. I was on a Coast Guard icebreaker in the Bering sea, and I became enthralled by these researchers who were radio tagging sea lions to study their feeding and migrating habits. Those scientists were dressed in all white homemade hooded body suits and boots to blend in with the ice. They used bow and arrows to shoot the tags into the lions’ thick skin. They had to get on the small ship helicopter and fly out in search for sea lions, and it was very clear that they could not take me because that would mean that the helo could carry less fuel. But they sort of gave me hope that perhaps it could happen before the end of our stay. So, every day I would ask them. When we had a week left in the embark, some TV crews came on the icebreaker. There had been an NPR journalist with us for a few weeks already. Everyone of course was very intimidated by her. Things got a chaotic with the presence of large TV crews and people coming on and off the ship. I felt anxious and desperate to make my photograph. It became clear I would never get on the helo so I got the scientists to “repeat” I am pretty sure I did not use the word pretend and do what they normally do on the side of the ship for me to photograph them the next time we stop by a large ice floe. When it happened, the TV crews just got really excited when they saw me and the scientists in white suits clamber down to the ice. They rushed down and dominated the space…my space that I worked to hard to set up. I was able to make them stand back and wait their turn. And as I was about to expose my film, the NPR journalist ran down and started admonishing everyone, “How could you do this? This is a reenactment. Shame on you.” And I was just terrified. She continued yelling, and then I tried to apologize. “No, no, don't worry. You’re, okay. It’s them.” So, she gave me the pass, but it was clear the news crew was breaking the code of ethics. So, they ended up filming me, photographing the biologists, and that was okay. It was an important moment for me. It motivated me to mine these moments that allowed for great ambiguity and for wider space for interpretation.

An My Lê: I first heard when I was in graduate school studying with Todd Papageorge and Richard Benson, that all photography’s fiction. At first I struggled to come to terms with that, because you connect photography, at least the photography that I love with this idea of going out into the real world. It’s about discovering and photographing something about the real world. There is a dichotomy. But Richard had often talked about how photography produces images that are stunning in their depiction of reality because the lenses used to make pictures are close relatives of the organic lenses that provide us with eyesight. It is no wonder that pictures made this way look so much like the world we see. But he went on to say that a difficult side effect of this similarity is that viewers of photographs almost always confuse the pictures with some idea of truth about the world."

I think that what photography does, and it all depends on who has the hand, is creating relationships, is to give more importance to certain things than other things, is to create tensions, to create ambiguity and set the stage for potentials for interpretation. In that sense, it's all fictional and it's all constructed by the maker.

TiP: I think it is a complicated subject, that it is something that we live, particularly in today's world, where there is this great denial of truth in image making. For me, truth is subjective. It's personal, it’s perception. It's a feeling. It's intangible.

Lê: I think it's obvious that I'm not a photojournalist. I do believe in facts. I was trained as a scientist. So, for me, the notion of truth is very subjective, just like it is for you, but I believe in the facts. And I want to see the facts and the facts will help me decide.

I think there's quite a strong structure that is factual in photography. It has to do with the light. It has to do with the details and how things are described again. There's no artist who would not take advantage of this notion of truth, the subjectivity of truth, because there's no ethical code for us. When I did a short story for The New York Times last year, it was always, “Was this Photoshopped? Was this added, or is there anything that was manipulated?” So I think there's a code of ethics that photojournalists have to follow. And I don't. And I think there's a long story that I've told at various times that is relevant. I was on a Coast Guard icebreaker in the Bering sea, and I became enthralled by these researchers who were radio tagging sea lions to study their feeding and migrating habits. Those scientists were dressed in all white homemade hooded body suits and boots to blend in with the ice. They used bow and arrows to shoot the tags into the lions’ thick skin. They had to get on the small ship helicopter and fly out in search for sea lions, and it was very clear that they could not take me because that would mean that the helo could carry less fuel. But they sort of gave me hope that perhaps it could happen before the end of our stay. So, every day I would ask them. When we had a week left in the embark, some TV crews came on the icebreaker. There had been an NPR journalist with us for a few weeks already. Everyone of course was very intimidated by her. Things got a chaotic with the presence of large TV crews and people coming on and off the ship. I felt anxious and desperate to make my photograph. It became clear I would never get on the helo so I got the scientists to “repeat” I am pretty sure I did not use the word pretend and do what they normally do on the side of the ship for me to photograph them the next time we stop by a large ice floe. When it happened, the TV crews just got really excited when they saw me and the scientists in white suits clamber down to the ice. They rushed down and dominated the space…my space that I worked to hard to set up. I was able to make them stand back and wait their turn. And as I was about to expose my film, the NPR journalist ran down and started admonishing everyone, “How could you do this? This is a reenactment. Shame on you.” And I was just terrified. She continued yelling, and then I tried to apologize. “No, no, don't worry. You’re, okay. It’s them.” So, she gave me the pass, but it was clear the news crew was breaking the code of ethics. So, they ended up filming me, photographing the biologists, and that was okay. It was an important moment for me. It motivated me to mine these moments that allowed for great ambiguity and for wider space for interpretation.

TiP: I think that's a very interesting point about this idea of reenactment somehow being less true than something that's happening. If you're engaging with your subject and you're asking them, “Could you show me how you do this?” Is that really any less true than just doing it?

Lê: Newspaper and magazine are concerned with the seamless moment that a photographer can witness unfolding. It’s rather impossible to achieve that with the camera, it's very difficult in that you have to ask someone to hold still or redo something. I am not so interested in whether something is more or less “true” but I am obsessed with things looking convincing even though posed.

TiP: When you are making photographs and doing your work, are you hoping for a certain kind of response?

Lê: No, I don't hope for responses. I don't really think about how the photographs are going to be viewed.

TiP: It’s interesting to me the way in which you use the landscape. When you're photographing a landscape, what are you after? What excites you in terms of looking at a landscape? Because there's a transformative power that I think landscapes have.

Lê: The landscape allows me to work on different levels, from the specificity of describing those leaves and the grass and the river and the tree, or some human activity, and to oppose that to the greater forces such as the air and the weather. From something small to something larger and perhaps uncontrollable. Being able to create this sense of scale allows you to move back and forth and think about the current moment as much as the past or the future. It is easy to feel insignificant in a landscape so it is my desire to engage with what is epic. I like the notion of allowing people to wander intellectually or even physically if they feel that they can walk into the photograph. They're guided by the specificity, the described facts that we talked about, but then once they get drawn in, it's all up to them what kind of journey they want to take. I think some people feel a particular way about some photographs I’ve made, but they could feel the opposite way. I've had people look at photographs of 29 Palms and say, “This is such an incredible statement against war...” Someone else said, “This young man and woman look so glorious, and they're rising up to the occasion.” I don't think they were saying, “It's great that there's a war for them to step up to,” but they see something different. These topics are complicated and I believe in photography’s power to engage with them in complex ways.

Lê: Newspaper and magazine are concerned with the seamless moment that a photographer can witness unfolding. It’s rather impossible to achieve that with the camera, it's very difficult in that you have to ask someone to hold still or redo something. I am not so interested in whether something is more or less “true” but I am obsessed with things looking convincing even though posed.

TiP: When you are making photographs and doing your work, are you hoping for a certain kind of response?

Lê: No, I don't hope for responses. I don't really think about how the photographs are going to be viewed.

TiP: It’s interesting to me the way in which you use the landscape. When you're photographing a landscape, what are you after? What excites you in terms of looking at a landscape? Because there's a transformative power that I think landscapes have.

Lê: The landscape allows me to work on different levels, from the specificity of describing those leaves and the grass and the river and the tree, or some human activity, and to oppose that to the greater forces such as the air and the weather. From something small to something larger and perhaps uncontrollable. Being able to create this sense of scale allows you to move back and forth and think about the current moment as much as the past or the future. It is easy to feel insignificant in a landscape so it is my desire to engage with what is epic. I like the notion of allowing people to wander intellectually or even physically if they feel that they can walk into the photograph. They're guided by the specificity, the described facts that we talked about, but then once they get drawn in, it's all up to them what kind of journey they want to take. I think some people feel a particular way about some photographs I’ve made, but they could feel the opposite way. I've had people look at photographs of 29 Palms and say, “This is such an incredible statement against war...” Someone else said, “This young man and woman look so glorious, and they're rising up to the occasion.” I don't think they were saying, “It's great that there's a war for them to step up to,” but they see something different. These topics are complicated and I believe in photography’s power to engage with them in complex ways.

I have my own biases, of course, and it's from growing up in Vietnam and experiencing very contradicting forces, seeing the devastation of the war, but then also seeing how lives can be changed because somebody stepped in and did something for you. I see the military as such a conflicting force military.

TiP: In talking about Vietnam, what year was it that your family left?

Lê: We left at the end of the war in 1975, and our departure was not quite as tragic as it was for many other families who escaped by fishing boats from the coast line. We were separated and lost track of my mom for a few months. We didn't spend weeks drifting at sea and were not attacked by pirates but it was traumatic enough.

TiP: When did you get your first camera?

Lê: Not until 1986.

TiP: So, you didn’t have a camera when you were a child growing up?

Lê: No, no, no. I think my brother may have had a camera, and so I did take a trip to Paris at one point, and I may have used his camera, but it was his. I was not that interested. I found photography by chance when I was in my mid-twenties when I was getting a Master’s in Biology. I wanted to take a drawing class to fulfill a non-science requirement. It was full so I took photography.

TiP: When you went back to Vietnam, I find those photographs of yours really evocative. Seeing your photographs and seeing the landscapes, it made me think about the truth of reality, the truth of the image. There's a sense that maybe the truth is what we're imagining, rather than what we're seeing, because what we're seeing is the landscape. We're imagining the context of this in a different time.

Lê: Context has always been really important to me. Even growing up as a kid, after 1975, it was very difficult to find photographs not related to war. I was always looking anything that spoke about Vietnamese life and culture. What I found was taken by French photographers or dated back to the colonial times. They were kind of expositions of what the Vietnamese people and culture are about. By default, I became obsessed with the peripheral information I could gather about life in Vietnam from news photographs such as the one of the monk self-immolating in the street. There were always details in the corners and context that showed something about the normalcy of life, that I was always so drawn to.

TiP: In talking about Vietnam, what year was it that your family left?

Lê: We left at the end of the war in 1975, and our departure was not quite as tragic as it was for many other families who escaped by fishing boats from the coast line. We were separated and lost track of my mom for a few months. We didn't spend weeks drifting at sea and were not attacked by pirates but it was traumatic enough.

TiP: When did you get your first camera?

Lê: Not until 1986.

TiP: So, you didn’t have a camera when you were a child growing up?

Lê: No, no, no. I think my brother may have had a camera, and so I did take a trip to Paris at one point, and I may have used his camera, but it was his. I was not that interested. I found photography by chance when I was in my mid-twenties when I was getting a Master’s in Biology. I wanted to take a drawing class to fulfill a non-science requirement. It was full so I took photography.

TiP: When you went back to Vietnam, I find those photographs of yours really evocative. Seeing your photographs and seeing the landscapes, it made me think about the truth of reality, the truth of the image. There's a sense that maybe the truth is what we're imagining, rather than what we're seeing, because what we're seeing is the landscape. We're imagining the context of this in a different time.

Lê: Context has always been really important to me. Even growing up as a kid, after 1975, it was very difficult to find photographs not related to war. I was always looking anything that spoke about Vietnamese life and culture. What I found was taken by French photographers or dated back to the colonial times. They were kind of expositions of what the Vietnamese people and culture are about. By default, I became obsessed with the peripheral information I could gather about life in Vietnam from news photographs such as the one of the monk self-immolating in the street. There were always details in the corners and context that showed something about the normalcy of life, that I was always so drawn to.

I never thought of myself as a landscape photographer. I came to Yale with the experience of having worked in Paris as a staff photographer for a guild of skilled craftsmen, the people who built the churches and cathedrals of France during the Middle Ages, and the Gothic times. I sort of cut my teeth photographing architectural details as well as documenting new constructions and restorations of monuments. I had been spending a lot of time on my own making portraits of craftsmen, studios, and workshops. I came to Yale with this kind of work. I was encouraged to experiment especially landscape. It was all a failure probably because I did not feel connected to the history of the North East.

It was such a revelation to re-experience the Vietnamese landscape and figuring out how to photograph it. Strangely enough my understanding of placement, of scale, of what mattered, what didn't matter happened effortlessly. The landscape was certainly not familiar, we never traveled much outside of Saigon when I was growing up, but there was instant recognition and acknowledgement because I was searching for that landscape my grandmother and mother had so well described in their tales about living in northern Vietnam in the 40s and 50s, or what it meant to evacuate Hanoi to move to the country side during the Japanese occupation, or what it meant to move south in 1954. I think connecting with the landscape represented a kind of coming home to me, much more than making a portrait of someone. I see the portrait as so much about that moment, that person or that psychology. The landscape really was transcendent because it allowed me to express a yearning for a childhood I never had.

It was such a revelation to re-experience the Vietnamese landscape and figuring out how to photograph it. Strangely enough my understanding of placement, of scale, of what mattered, what didn't matter happened effortlessly. The landscape was certainly not familiar, we never traveled much outside of Saigon when I was growing up, but there was instant recognition and acknowledgement because I was searching for that landscape my grandmother and mother had so well described in their tales about living in northern Vietnam in the 40s and 50s, or what it meant to evacuate Hanoi to move to the country side during the Japanese occupation, or what it meant to move south in 1954. I think connecting with the landscape represented a kind of coming home to me, much more than making a portrait of someone. I see the portrait as so much about that moment, that person or that psychology. The landscape really was transcendent because it allowed me to express a yearning for a childhood I never had.

TiP: I think it's interesting how the landscape becomes evocative of human emotion. And you know what, you're talking about it, the personal elements that it's in, what you're seeing. And so, I mean, I think that comes through in your work, that it did that, that there's something that the landscape becomes charged with feeling, maybe, or, you know, we see that, you know, there's the natural beauty of the landscape. But then there’s the emotional component, which is a little bit harder to describe because it's defined in composition and light…

Lê: It's also the fact that it had endured through time, and somehow I still found myself, I still found my family's history in there. It’s extraordinary. I think people change, and I think people were changed by the war. There's a contemporary aspect to Vietnam that I could observe at the top, but I could still see all the various layers going back to the time that perhaps I would have known if the country had not been divided. The landscape revealed itself as an immutable presence in spite of the violence and devastation inflicted by decades of war.

TiP: It's the truth of the landscape, because the truth of the landscape is that it does endure.

Lê: It has a persistence; it has a longevity. I found hope in the way things renew, in the way things get rebuilt.

TiP: Do you feel that when you're looking at the landscape in this country or in other places, that it’s a different process? How would you describe your way of seeing? How does it change?

Lê: That’s how I got me started, and perhaps it's kind of like training wheels. My underlying interest is the notion of labor. The early pictures were so much about the way the Vietnamese worked the land in a manual way still. I am looking at tomato fields covered in beautifully built trellises, properties are enclosed by walls covered in cow dung disks that would be used to fire ceramics, gardens delineated by windy paths delineated by trimmed bushes and vegetable patches. This helped me understand the drawing of the land from the investment of labor. From there it was easy to jump to a different kind of drawing, whether it’s the international bridge from Presidio to Ojinaga or something more industrial. It was not necessarily an easy jump, but I've been able to make that jump.

Lê: It's also the fact that it had endured through time, and somehow I still found myself, I still found my family's history in there. It’s extraordinary. I think people change, and I think people were changed by the war. There's a contemporary aspect to Vietnam that I could observe at the top, but I could still see all the various layers going back to the time that perhaps I would have known if the country had not been divided. The landscape revealed itself as an immutable presence in spite of the violence and devastation inflicted by decades of war.

TiP: It's the truth of the landscape, because the truth of the landscape is that it does endure.

Lê: It has a persistence; it has a longevity. I found hope in the way things renew, in the way things get rebuilt.

TiP: Do you feel that when you're looking at the landscape in this country or in other places, that it’s a different process? How would you describe your way of seeing? How does it change?

Lê: That’s how I got me started, and perhaps it's kind of like training wheels. My underlying interest is the notion of labor. The early pictures were so much about the way the Vietnamese worked the land in a manual way still. I am looking at tomato fields covered in beautifully built trellises, properties are enclosed by walls covered in cow dung disks that would be used to fire ceramics, gardens delineated by windy paths delineated by trimmed bushes and vegetable patches. This helped me understand the drawing of the land from the investment of labor. From there it was easy to jump to a different kind of drawing, whether it’s the international bridge from Presidio to Ojinaga or something more industrial. It was not necessarily an easy jump, but I've been able to make that jump.

TiP: And you see it with fresher eyes. You see it as it is today. Not having those ties to a place can also free you to see the place perhaps as people who don't live there see.

Lê: I think that making those pictures in Vietnam freed me up. Being able to inscribe the landscape on film was transcending in that it brought a lot of closure. “Okay, I got it, it’s on film.” I can move on to something else. I was able to come back to the United States and feel that I was an artist first, I was a Vietnamese American second and that my home was actually here. This allowed me to feel implicated and become engaged. I was able to really look at the social political problems that were bursting out of the seams here, leading up to four years of the Trump presidency, Covid and many other current issues.

TiP: You were talking about your image making as kind of drawing. How do you connect photography to drawing in that sense?

Lê: When I'm looking at a landscape, I immediately see the sketch. It's not for me, how this lies on top of this, I think of how things are drawn. How do you see that drawing the best? If you stand up here, then that line is different. If you stand over here... So why do I use the word drawing? Drawing is a kind of mapping that is inherent to Black and White photography. I was inspired by the work of landscape designers such as Olmsted and the notion of pathways to guide visitors and provide a particular experience of space such as Central Park by taking them from the meadow to the lake through granite fields. I try to accomplish something similar.

Lê: I think that making those pictures in Vietnam freed me up. Being able to inscribe the landscape on film was transcending in that it brought a lot of closure. “Okay, I got it, it’s on film.” I can move on to something else. I was able to come back to the United States and feel that I was an artist first, I was a Vietnamese American second and that my home was actually here. This allowed me to feel implicated and become engaged. I was able to really look at the social political problems that were bursting out of the seams here, leading up to four years of the Trump presidency, Covid and many other current issues.

TiP: You were talking about your image making as kind of drawing. How do you connect photography to drawing in that sense?

Lê: When I'm looking at a landscape, I immediately see the sketch. It's not for me, how this lies on top of this, I think of how things are drawn. How do you see that drawing the best? If you stand up here, then that line is different. If you stand over here... So why do I use the word drawing? Drawing is a kind of mapping that is inherent to Black and White photography. I was inspired by the work of landscape designers such as Olmsted and the notion of pathways to guide visitors and provide a particular experience of space such as Central Park by taking them from the meadow to the lake through granite fields. I try to accomplish something similar.

TiP: The first time I looked at the cigarette lighters in your exhibition đô-mi-nô, I thought they were just photographs of lighters. And then I realized that they were real, and you had actually done these weavings. Where did you get the lighters?

Lê: On eBay, but they were made in Japan or China and they're all very different. I came across one when I went to buy used furniture a few years ago. And then when Covid started, I spent a lot of time looking for supplies and researching these lighters online. I couldn't find much information but stumbled back on images of the vintage Vietnam era lighters. I have accumulated 125-130 jumbo ones. The bidding and hoarding got a little obsessive. I would say that 90 percent of the engravings are word for word lifted from Vietnam-era inscriptions. I took out details that refer too specifically to the war. And they resonate. They talk about racial injustice but also racial empowerment, they talk about relationships, love, fate and the absurd.

Lê: On eBay, but they were made in Japan or China and they're all very different. I came across one when I went to buy used furniture a few years ago. And then when Covid started, I spent a lot of time looking for supplies and researching these lighters online. I couldn't find much information but stumbled back on images of the vintage Vietnam era lighters. I have accumulated 125-130 jumbo ones. The bidding and hoarding got a little obsessive. I would say that 90 percent of the engravings are word for word lifted from Vietnam-era inscriptions. I took out details that refer too specifically to the war. And they resonate. They talk about racial injustice but also racial empowerment, they talk about relationships, love, fate and the absurd.

TiP: Do you see a connection between your lighter project and your photographs?

Le: I think that they vibrate in the same register as my photographs. There is really specificity to them, a kind of evidentiary specificity. They function on multiple levels: as found objects, as as mementos or memorials and as sculpture. They speak about the past but also the present and point to the future.

TiP: Where do you see your work going now? Do you have a sense of a new direction?

Le: People have asked me about this big shift in my process with the lighters. I don't really see it as a shift. I just felt that they say things that I've always wanted to say through photography. I still feel like myself if you know what I mean. The project has allowed me to synthesize my interests with peripheral obsessions. I certainly am excited by a new found freedom. It’s almost as if anything is possible. I just have to not overreach.

Le: I think that they vibrate in the same register as my photographs. There is really specificity to them, a kind of evidentiary specificity. They function on multiple levels: as found objects, as as mementos or memorials and as sculpture. They speak about the past but also the present and point to the future.

TiP: Where do you see your work going now? Do you have a sense of a new direction?

Le: People have asked me about this big shift in my process with the lighters. I don't really see it as a shift. I just felt that they say things that I've always wanted to say through photography. I still feel like myself if you know what I mean. The project has allowed me to synthesize my interests with peripheral obsessions. I certainly am excited by a new found freedom. It’s almost as if anything is possible. I just have to not overreach.

|

|

Delve deeper |