This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the PhotographerOlivia Arthur is a London-based photographer who has worked for many years on the East-West cultural divide. Her first book Jeddah Diary was about the lives of young women in Saudi Arabia. Her second book, Stranger, is a journey into Dubai seen through the eyes of the survivor of a shipwreck. Her work has been exhibited internationally and has been included in institutional collections in the UK, USA, Germany, and Switzerland. She is co-founder of Fishbar, a publisher and space for photography in London. She is a member of Magnum Photos. |

|

Truth in Photography: Do you think of truth when you work?

Olivia Arthur: I do. I mean a word that I use a lot when I talk about photography or when I think about how photography is used is ambiguity, actually. I don't think that truth and ambiguity are incompatible or mutually exclusive, but I think it's that combination that makes it interesting and challenging. You have a slice of truth that’s surrounded by a lot of ambiguity. And that’s, to me, what makes photography linger. This feeling that you can't quite tell what's just outside the frame. What’s happening just before. What's happening just after. And that part for me is really interesting.

TiP: I think that idea of what's before the frame and after is very interesting.

Arthur: I do a lot of portraiture. I worked with this Indian photographer, Bharat Sikka, and we did a collaboration together. Sometimes we'd both photograph people in the same place, maybe one after the other, sometimes on separate occasions. And he kind of laughed at me because I would make my portrait, and I'd put the camera away, and then we’d be sitting down and maybe having a cup of tea or smoking a cigarette with people. And then I'd be like, “Okay, wait.” And then I'd get the camera out and do it all again. And then I'd get my picture then at the end. There's almost a performance of making a portrait, and there's an expectation that comes with it and when that sort of expectation comes down, you see something else.

Olivia Arthur: I do. I mean a word that I use a lot when I talk about photography or when I think about how photography is used is ambiguity, actually. I don't think that truth and ambiguity are incompatible or mutually exclusive, but I think it's that combination that makes it interesting and challenging. You have a slice of truth that’s surrounded by a lot of ambiguity. And that’s, to me, what makes photography linger. This feeling that you can't quite tell what's just outside the frame. What’s happening just before. What's happening just after. And that part for me is really interesting.

TiP: I think that idea of what's before the frame and after is very interesting.

Arthur: I do a lot of portraiture. I worked with this Indian photographer, Bharat Sikka, and we did a collaboration together. Sometimes we'd both photograph people in the same place, maybe one after the other, sometimes on separate occasions. And he kind of laughed at me because I would make my portrait, and I'd put the camera away, and then we’d be sitting down and maybe having a cup of tea or smoking a cigarette with people. And then I'd be like, “Okay, wait.” And then I'd get the camera out and do it all again. And then I'd get my picture then at the end. There's almost a performance of making a portrait, and there's an expectation that comes with it and when that sort of expectation comes down, you see something else.

TiP: Do you feel like you see something deeper in the person, are they more relaxed or less aware?

Arthur: Sometimes it's the intensity of the moment when you're making the portrait that you want to capture. But then there's this moment afterwards where everything sort of falls off and maybe you get something more revealing, because they let their guard down in this way. Then you suddenly see they opened up in a sense. Particularly, if they're feeling nervous about having a photograph done. So, you see something in that way. It depends, of course. Sometimes the intensity brings out something else. When you take a portrait of somebody, you're trying to coax something out that gives you a little bit of that person, right? Because they're often quite brief these encounters. You're trying to set up an environment, a situation where they will share that bit of themselves with you, with the camera, and sometimes it comes through, maybe at the end when they let everything down, that comes out. It's not necessarily more true. I talk about it as looking for this point where people feel comfortable in themselves and some people feel comfortable with that performance of having a photograph made and the formality of it. And some people feel more comfortable when it's off. Right? I talk a lot about this idea of people feeling comfortable in their own skin, and looking for that moment when they feel that way. And for some people it's really noticeable that in front of the camera they step into that role, and it’s somebody who seems quite shy. They go in front of the camera and they take on this pose of sitting in front of it and what they can feel they can give themselves to the camera. And that's great. That's something I've seen happen. And it's not everybody. Not everybody can do that. Other people really need to have their little comfort to feel that way. But it varies and I think that's interesting.

Arthur: Sometimes it's the intensity of the moment when you're making the portrait that you want to capture. But then there's this moment afterwards where everything sort of falls off and maybe you get something more revealing, because they let their guard down in this way. Then you suddenly see they opened up in a sense. Particularly, if they're feeling nervous about having a photograph done. So, you see something in that way. It depends, of course. Sometimes the intensity brings out something else. When you take a portrait of somebody, you're trying to coax something out that gives you a little bit of that person, right? Because they're often quite brief these encounters. You're trying to set up an environment, a situation where they will share that bit of themselves with you, with the camera, and sometimes it comes through, maybe at the end when they let everything down, that comes out. It's not necessarily more true. I talk about it as looking for this point where people feel comfortable in themselves and some people feel comfortable with that performance of having a photograph made and the formality of it. And some people feel more comfortable when it's off. Right? I talk a lot about this idea of people feeling comfortable in their own skin, and looking for that moment when they feel that way. And for some people it's really noticeable that in front of the camera they step into that role, and it’s somebody who seems quite shy. They go in front of the camera and they take on this pose of sitting in front of it and what they can feel they can give themselves to the camera. And that's great. That's something I've seen happen. And it's not everybody. Not everybody can do that. Other people really need to have their little comfort to feel that way. But it varies and I think that's interesting.

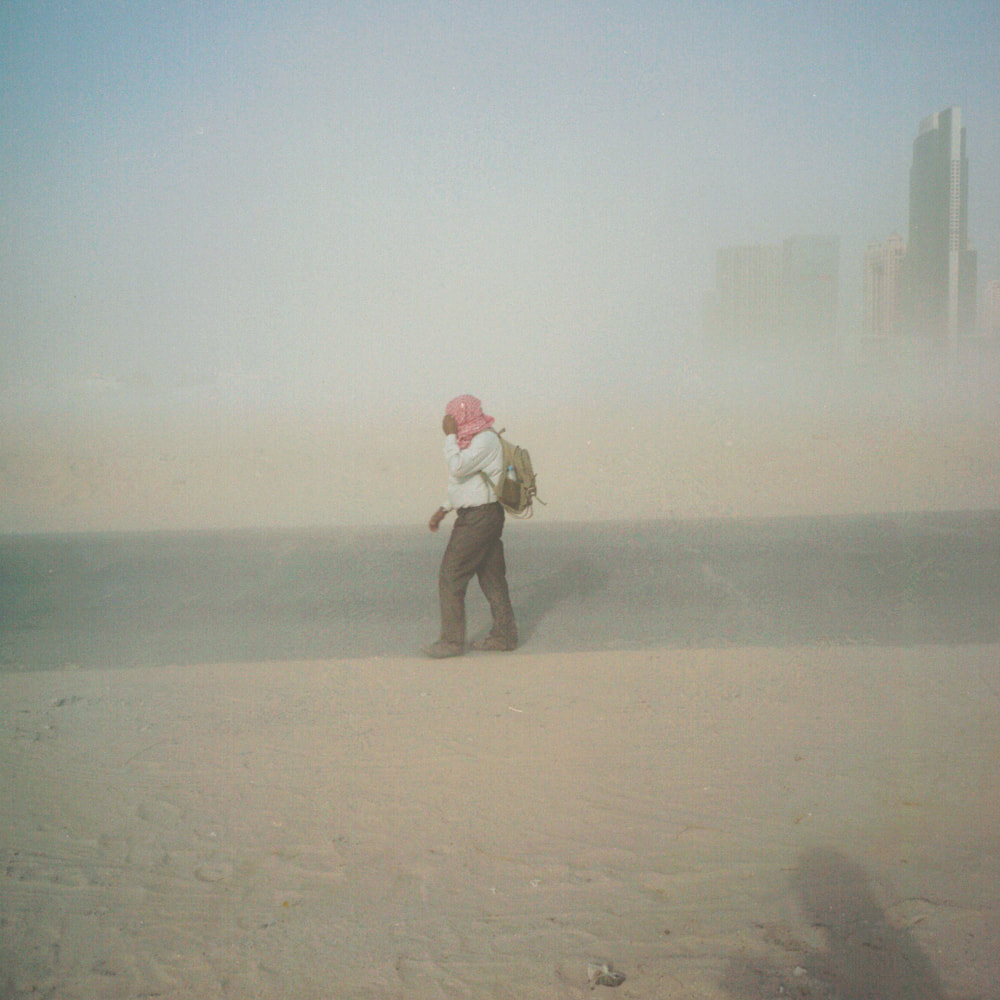

TiP: I'm particularly drawn to a lot of these night scenes where you don't really know what's going on, and particularly things in the Middle East where there's a sense of mystery. There’s a sense of ambiguity, and they're very atmospheric, which kind of compels a more visceral kind of response. Could you talk about that work?

Arthur: I don't know if that's intentional. I go to these places looking to try and understand them. But that work in the Middle East, having spent quite a bit of time there, it's a very difficult place to fully understand as an outsider. I wouldn't say I got anywhere near understanding it, but I guess the feeling that you get in those pictures is that they kind of reflect that atmosphere. What does it feel like to be in this place? I think of that a lot when I think of making work, making series, putting a whole story together. You have this title here about truth, and this idea of telling truth, and obviously this photo journalistic urge to say this is what's happening somewhere. And when I found myself in places where I come away from it saying, I can't really tell you what happens in this place at all, but this is what it felt like for me. I suppose that's what those photographs do. They give you that feeling of being in a place and whether it's in a street at night or in somebody's house with just a tiny sidelight on, I suppose that’s what I'm trying to capture there. I'm looking for a feeling as much as I'm looking for truth in those things. I spent time in Saudi Arabia and I think for me to talk about truth there would be extremely difficult because all I can say is, “This is what I saw.” And it took me quite a long time to put that work together, for exactly that reason, because everything’s so contradictory, nothing seems to make any sense. You’ve got so many different kinds of worlds and different sets of rules that seem pretty rigid, but yet they change and morph when people are in different places. I came away from it really just feeling that all I could share was my experience and take people through what I had experienced because, particularly at that time, there was very, very little that you could see about what “ordinary life” is like there.

Arthur: I don't know if that's intentional. I go to these places looking to try and understand them. But that work in the Middle East, having spent quite a bit of time there, it's a very difficult place to fully understand as an outsider. I wouldn't say I got anywhere near understanding it, but I guess the feeling that you get in those pictures is that they kind of reflect that atmosphere. What does it feel like to be in this place? I think of that a lot when I think of making work, making series, putting a whole story together. You have this title here about truth, and this idea of telling truth, and obviously this photo journalistic urge to say this is what's happening somewhere. And when I found myself in places where I come away from it saying, I can't really tell you what happens in this place at all, but this is what it felt like for me. I suppose that's what those photographs do. They give you that feeling of being in a place and whether it's in a street at night or in somebody's house with just a tiny sidelight on, I suppose that’s what I'm trying to capture there. I'm looking for a feeling as much as I'm looking for truth in those things. I spent time in Saudi Arabia and I think for me to talk about truth there would be extremely difficult because all I can say is, “This is what I saw.” And it took me quite a long time to put that work together, for exactly that reason, because everything’s so contradictory, nothing seems to make any sense. You’ve got so many different kinds of worlds and different sets of rules that seem pretty rigid, but yet they change and morph when people are in different places. I came away from it really just feeling that all I could share was my experience and take people through what I had experienced because, particularly at that time, there was very, very little that you could see about what “ordinary life” is like there.

TiP: What years did you do that work?

Arthur: I was in Saudi Arabia in 2009 and 2010, and then off the back of that I published that book then in 2012, and then I was invited to Dubai, and I made work in Dubai, but quite different work in a way because I wanted to move away from some of the themes that I had been looking at in Saudi Arabia. Also, because it's really a very different place. It's still the Middle East and there are still a lot of similarities, but it’s very different in many ways.

TiP: I think the point that you're making about that work there is for me a deep honesty. It's the honesty of the maker. Because the photographs do not pretend to say, “I understand this reality.” I could connect to your photos even though I was never in that place, because by doing it with the honesty that you do, it universalizes the experience.

Arthur: I'm happy to hear you use that word. I think the word “honesty” for me is more important than truth. And actually, after I made that work, around 2015, I had a bit of a shift in my practice, and I started working on a large format camera. And then I completely fell in love with working on that format, large format on five-four, a combination of Linhoff and Graflex. But the word that I found that I use a lot when I was trying to explain to people why I fell in love with this way of working was that it felt honest. Making a picture in that way, it’s slow and it's cumbersome, but it feels very honest. You're not grabbing and running, you're thinking about it and you're engaging. And that really appealed to me.

Arthur: I was in Saudi Arabia in 2009 and 2010, and then off the back of that I published that book then in 2012, and then I was invited to Dubai, and I made work in Dubai, but quite different work in a way because I wanted to move away from some of the themes that I had been looking at in Saudi Arabia. Also, because it's really a very different place. It's still the Middle East and there are still a lot of similarities, but it’s very different in many ways.

TiP: I think the point that you're making about that work there is for me a deep honesty. It's the honesty of the maker. Because the photographs do not pretend to say, “I understand this reality.” I could connect to your photos even though I was never in that place, because by doing it with the honesty that you do, it universalizes the experience.

Arthur: I'm happy to hear you use that word. I think the word “honesty” for me is more important than truth. And actually, after I made that work, around 2015, I had a bit of a shift in my practice, and I started working on a large format camera. And then I completely fell in love with working on that format, large format on five-four, a combination of Linhoff and Graflex. But the word that I found that I use a lot when I was trying to explain to people why I fell in love with this way of working was that it felt honest. Making a picture in that way, it’s slow and it's cumbersome, but it feels very honest. You're not grabbing and running, you're thinking about it and you're engaging. And that really appealed to me.

TiP: Can you complete the sentence, truth in photography is…

Arthur: Truth in photography is difficult to pin down. I think it's there, but it's surrounded by lots of other things, too.

TiP: Ultimately, truth in photography is completely subjective because of the way in which the medium reveals itself. We have to frame the image. There are issues of composition. There’s framing, and we all understand, particularly in crisis situations, how framing affects perception of what's going on.

Arthur: There's framing, there's timing, but there's also engagement. And I think that’s something that is important, beyond the way you handle a camera and how you make your frames, is how you engage with what's happening around you. That can be whether you're in the middle of something really hectic in a very urgent news situation or in a quiet spot in somebody's house.

TiP: Engagement is perhaps the most important because the nature of the engagement that you have should lead you in the way you work. Rather than coming into a situation where you have a preconceived idea of what you want to show, it's through engagement that you gain some understanding of what you're photographing.

Arthur: To me, it goes both ways. I think it's essential that people engage and think about what they're photographing. But I think it also goes the other way around as well. It's the way that people look at you. People talk a lot about the eye of the photographer. To me, that's just one part of it. The way people look at me as the photographer is a big part of how the images will look.

Arthur: Truth in photography is difficult to pin down. I think it's there, but it's surrounded by lots of other things, too.

TiP: Ultimately, truth in photography is completely subjective because of the way in which the medium reveals itself. We have to frame the image. There are issues of composition. There’s framing, and we all understand, particularly in crisis situations, how framing affects perception of what's going on.

Arthur: There's framing, there's timing, but there's also engagement. And I think that’s something that is important, beyond the way you handle a camera and how you make your frames, is how you engage with what's happening around you. That can be whether you're in the middle of something really hectic in a very urgent news situation or in a quiet spot in somebody's house.

TiP: Engagement is perhaps the most important because the nature of the engagement that you have should lead you in the way you work. Rather than coming into a situation where you have a preconceived idea of what you want to show, it's through engagement that you gain some understanding of what you're photographing.

Arthur: To me, it goes both ways. I think it's essential that people engage and think about what they're photographing. But I think it also goes the other way around as well. It's the way that people look at you. People talk a lot about the eye of the photographer. To me, that's just one part of it. The way people look at me as the photographer is a big part of how the images will look.

TiP: In your current work, you continue to explore these themes and it seems that issues of culture, identity, gender are particularly important to you. It seems like that's a thread through your work. Where is that leading you now?

Arthur: Well, that's a good question. I've been working on these themes and actually made quite a large amount of work on issues around gender issues, around sexuality, the body, identity. Right now, I'm looking at bringing all of that together. It's been a while since I made a book because I got quite busy with having children and being the president of Magnum. It's time for me now to take a step back a little bit and put some things out in the world. I also have a tendency to do lots of different things. I made a little short film and I'm working on another film project. I made a children's book and I have this ongoing project that I need to get back to that I started on the US-Mexico border the year before COVID came along. It's more than just the pictures that I made. It's an archive that I came across when I was working there. So it's looking at a history of a community there and a family.

TiP: And where is this on the border?

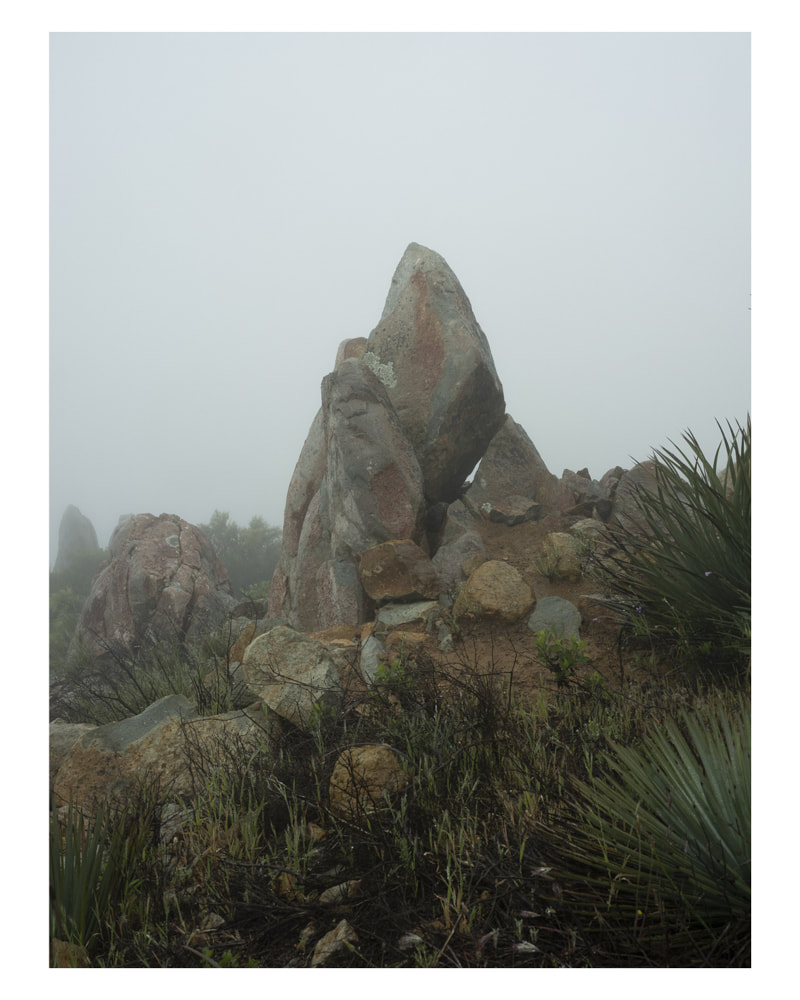

Arthur: Right down by San Diego and Tijuana. The work that I've been doing there, it's about this mountain at the border as you come outside San Diego. There's a mountain called Otay Mountain, and it's surprising, because very soon after the city and the sea, it goes up, and the mountain is quite tall. And so, the border fence comes along, gets into the mountain, and then it just stops. And then on the other side of the mountain, it starts again. But you’re only a handful of kilometers outside San Diego. So, it's outside Tijuana. So, it's pretty populated around there. The mountain becomes the border. My original thing was to go and see this mountain that becomes this obstacle, and it's considered steep enough and difficult enough to stop people crossing. But of course, people cross there a lot. And then it's also a wilderness. People go there to see various rare wildflowers. It is a recreational area on the US side. You have a gun range, so it's got all these different elements, just this one little mountain. It was about all these different perspectives on this one little bit of land, really. Then I met this woman whose in-laws’ family had settled there at the turn of the last century, and she had all these incredible photographs from her mother-in-law. Suitcases of mouse eaten photographs in the attic, which were quite amazing. Her mother in-law had been a keen photographer, and photographed life on the ranch. I got all these different elements. I have to do something more with it.

Arthur: Well, that's a good question. I've been working on these themes and actually made quite a large amount of work on issues around gender issues, around sexuality, the body, identity. Right now, I'm looking at bringing all of that together. It's been a while since I made a book because I got quite busy with having children and being the president of Magnum. It's time for me now to take a step back a little bit and put some things out in the world. I also have a tendency to do lots of different things. I made a little short film and I'm working on another film project. I made a children's book and I have this ongoing project that I need to get back to that I started on the US-Mexico border the year before COVID came along. It's more than just the pictures that I made. It's an archive that I came across when I was working there. So it's looking at a history of a community there and a family.

TiP: And where is this on the border?

Arthur: Right down by San Diego and Tijuana. The work that I've been doing there, it's about this mountain at the border as you come outside San Diego. There's a mountain called Otay Mountain, and it's surprising, because very soon after the city and the sea, it goes up, and the mountain is quite tall. And so, the border fence comes along, gets into the mountain, and then it just stops. And then on the other side of the mountain, it starts again. But you’re only a handful of kilometers outside San Diego. So, it's outside Tijuana. So, it's pretty populated around there. The mountain becomes the border. My original thing was to go and see this mountain that becomes this obstacle, and it's considered steep enough and difficult enough to stop people crossing. But of course, people cross there a lot. And then it's also a wilderness. People go there to see various rare wildflowers. It is a recreational area on the US side. You have a gun range, so it's got all these different elements, just this one little mountain. It was about all these different perspectives on this one little bit of land, really. Then I met this woman whose in-laws’ family had settled there at the turn of the last century, and she had all these incredible photographs from her mother-in-law. Suitcases of mouse eaten photographs in the attic, which were quite amazing. Her mother in-law had been a keen photographer, and photographed life on the ranch. I got all these different elements. I have to do something more with it.

TiP: So, you’re working on that project, and you see that becoming a book. It sounds like the archive is amazing because photographs of that nature are very scarce.

Arthur: I was fascinated to come across them and think of a woman at that point taking photographs. At that point, women in photography were in the cities. They were not out in the middle of nowhere. I'm not a historian on these kinds of things, but I was just really amazed. The photographs are great as well. They're not just snapshots. She was obviously really passionate about it. I became very fascinated by that. The woman that I had met is quite old now, she's in her nineties. I visited twice and on my second visit, it was the last day, and I was leaving the next morning, and then she said to me, “Oh yeah, and so my husband's book…” and I'm like, “What? Your husband's book?” And she's like, “Oh yeah, he wrote a book.” He spent ten years apparently writing this manuscript. It's not a published book. So, on my last evening I'm there, she goes into the back. When she comes out with this typewriter written massive manuscript with this family history through a series of anecdotes, I'm like, “Gosh.” I borrow it for the night, and I photograph it all. You can get it made into a book online. I had some copies made and sent it to her, so she finally got her husband’s book. But it gave me a chance to read it and it gave a whole interesting perspective. You have these photographs which are very much about family life, taken by the mother of the man who wrote the story, and the man who writes the story writes it very much from a male perspective. It's a lot about cowboys and ranch life and the ride to town, and it's interesting to me, but now I have to work to put it all together.

TiP: Does working on different types of projects interest you?

Arthur: I'm very interested in working in lots of different ways. I’m a big believer in working with words as well. The books that I've made so far have always had words in them. Not so much big texts as just snippets. I work with little extracts of words. I try and make them almost like photographs so they become abstracted from where they were. At least that's what I did in the first two books that I made. I'm interested in working in that way and putting lots of different things together.

Arthur: I was fascinated to come across them and think of a woman at that point taking photographs. At that point, women in photography were in the cities. They were not out in the middle of nowhere. I'm not a historian on these kinds of things, but I was just really amazed. The photographs are great as well. They're not just snapshots. She was obviously really passionate about it. I became very fascinated by that. The woman that I had met is quite old now, she's in her nineties. I visited twice and on my second visit, it was the last day, and I was leaving the next morning, and then she said to me, “Oh yeah, and so my husband's book…” and I'm like, “What? Your husband's book?” And she's like, “Oh yeah, he wrote a book.” He spent ten years apparently writing this manuscript. It's not a published book. So, on my last evening I'm there, she goes into the back. When she comes out with this typewriter written massive manuscript with this family history through a series of anecdotes, I'm like, “Gosh.” I borrow it for the night, and I photograph it all. You can get it made into a book online. I had some copies made and sent it to her, so she finally got her husband’s book. But it gave me a chance to read it and it gave a whole interesting perspective. You have these photographs which are very much about family life, taken by the mother of the man who wrote the story, and the man who writes the story writes it very much from a male perspective. It's a lot about cowboys and ranch life and the ride to town, and it's interesting to me, but now I have to work to put it all together.

TiP: Does working on different types of projects interest you?

Arthur: I'm very interested in working in lots of different ways. I’m a big believer in working with words as well. The books that I've made so far have always had words in them. Not so much big texts as just snippets. I work with little extracts of words. I try and make them almost like photographs so they become abstracted from where they were. At least that's what I did in the first two books that I made. I'm interested in working in that way and putting lots of different things together.

TiP: Is the book that you did in Saudi Arabia the first one?

Arthur: Yeah. In that one the texts really are like the missing photographs, because I was so often in situations where I couldn't photograph. I started by writing down these little anecdotes. Then in the book, the way it's laid out, they really are the sort of missing photographs. They are given the same weight as photographs. They don't relate to the pictures that are near them and they’re their own thing. The second book I made is called Stranger and is about Dubai. It's also a documentary work, but it was based on a sort of fictional premise of a real historical event, which was a shipwreck that happened in 1961 off the coast of Dubai. I felt like people come to Dubai and look at the fantastic, modern, forward-looking thing. I wanted to look backwards a little bit. And I came across this story of the shipwreck. And I also, whilst researching it, came across the story of a family who lost their son in the shipwreck, but believe that he's still alive. 50 years later, they were still searching for him, and they would put an ad out sometimes. It was kind of a crazy story. I took that as a starting point. What if someone could have disappeared in the shipwreck? If you took those 50 years away and he came to the city now, how would he see it? The idea was to see the city through those eyes and with those ears. So, I've used these little snippets of text of people I've interviewed or had conversations with, and I've actually recorded them and used verbatim snippets of text to piece together the sounds and the sights of the city. So, it's a little bit filmic. And towards the end of my stay there, I learned to dive, and I dive to the actual shipwreck and photograph the actual shipwreck. After this three-month residency I had, that was an amazing, very moving experience, I put it together on semi-transparent paper, and all the pictures blend into each other, which is an odd thing to do for a photographer, because you lose the individual picture, but you gain this feeling of the whole. It comes back to this idea of giving people a feeling of the experience of being somewhere.

Arthur: Yeah. In that one the texts really are like the missing photographs, because I was so often in situations where I couldn't photograph. I started by writing down these little anecdotes. Then in the book, the way it's laid out, they really are the sort of missing photographs. They are given the same weight as photographs. They don't relate to the pictures that are near them and they’re their own thing. The second book I made is called Stranger and is about Dubai. It's also a documentary work, but it was based on a sort of fictional premise of a real historical event, which was a shipwreck that happened in 1961 off the coast of Dubai. I felt like people come to Dubai and look at the fantastic, modern, forward-looking thing. I wanted to look backwards a little bit. And I came across this story of the shipwreck. And I also, whilst researching it, came across the story of a family who lost their son in the shipwreck, but believe that he's still alive. 50 years later, they were still searching for him, and they would put an ad out sometimes. It was kind of a crazy story. I took that as a starting point. What if someone could have disappeared in the shipwreck? If you took those 50 years away and he came to the city now, how would he see it? The idea was to see the city through those eyes and with those ears. So, I've used these little snippets of text of people I've interviewed or had conversations with, and I've actually recorded them and used verbatim snippets of text to piece together the sounds and the sights of the city. So, it's a little bit filmic. And towards the end of my stay there, I learned to dive, and I dive to the actual shipwreck and photograph the actual shipwreck. After this three-month residency I had, that was an amazing, very moving experience, I put it together on semi-transparent paper, and all the pictures blend into each other, which is an odd thing to do for a photographer, because you lose the individual picture, but you gain this feeling of the whole. It comes back to this idea of giving people a feeling of the experience of being somewhere.

|

TiP: You studied mathematics, and you talk about going from mathematics to photography. How do you feel your interest in mathematics has influenced you as a photographer? Or has it?

Arthur: It's a difficult one to pin down, because they are so different. I'm not a very technical photographer. Maths, when you get to that level, is very abstract, actually. I did a little bit of philosophy of maths as well. Maths is about looking for patterns and trying to understand things through patterns, right? The most I can see the link to photography is that you're trying to explain a bigger thing through looking at the details. That's the closest I get to explaining the link between the two. If you step back from that, maths is very rigorous, and a photo is very ambiguous. TiP: I think the core point that you just made makes perfect sense, which is that it is about the study of patterns and finding connections between patterns that reveal more information. Arthur: I have this feeling that as humans, we have this real instinct to look for patterns. It's in superstition, it's in religion. We have this need to look for patterns. |

|

|

Delve deeper |