|

|

About the PhotographerClarence Elie Rivera, a product of Latino migration, lives and works in New York City where he documents the shifting politics of immigration, labor, and urbanization. A life long project examines the impact of US-Puerto Rico relations on the lives of individuals residing on the continent and the island. His largest body of work “Legal Aliens: Gangsters, Musicians, the Neighborhood” spans two neighborhoods in NYC, The Lower East Side (Ludlow Street) and East Harlem, capturing the lives and activities of four generations. The affect of gentrification on traditionally Puerto Rican neighborhoods is highlighted in this work, and his scenes “provide a tumultuous vitality” of every day life in transition where they struggle to maintain their cultural identities and traditions. |

|

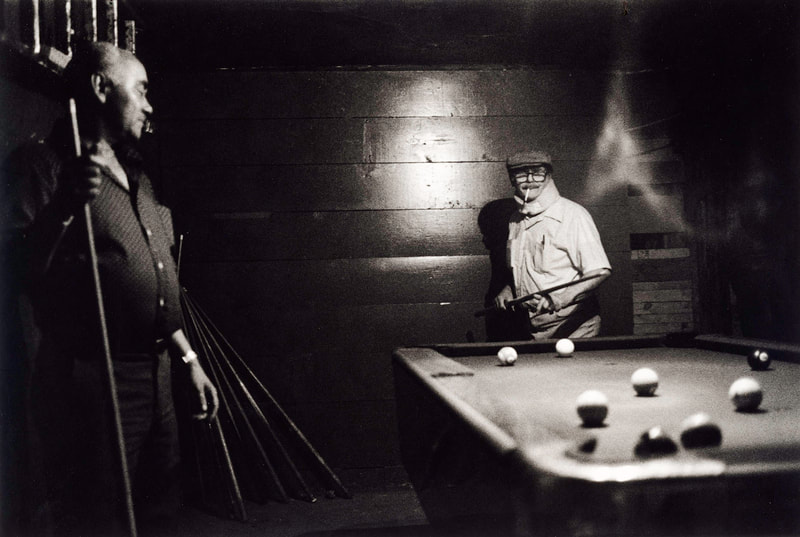

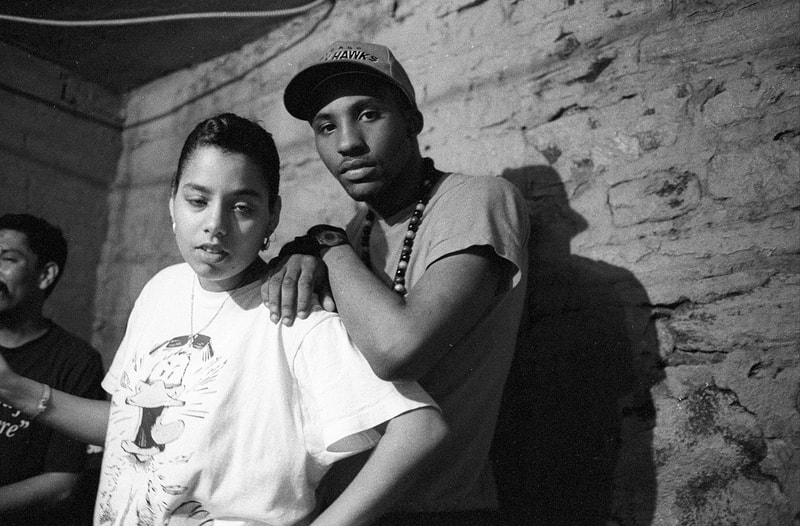

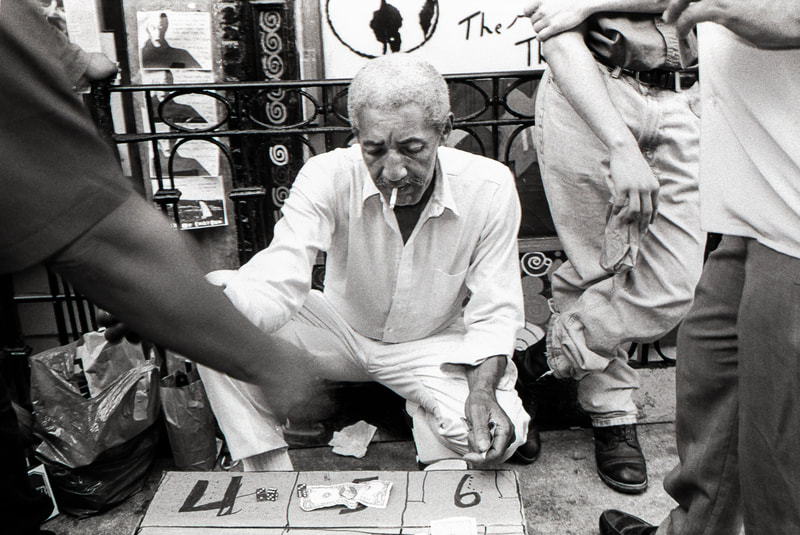

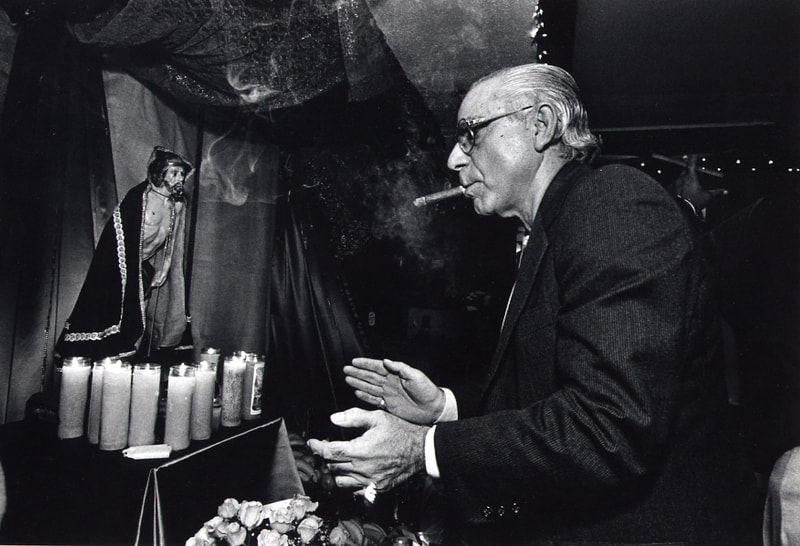

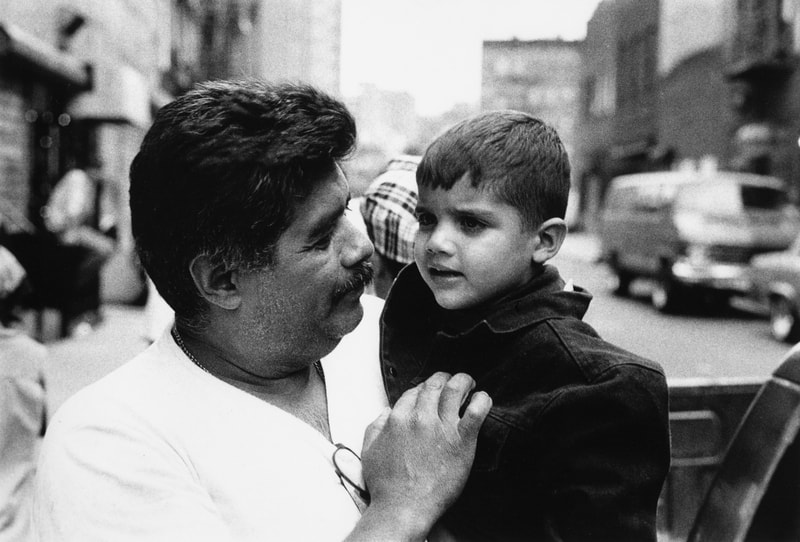

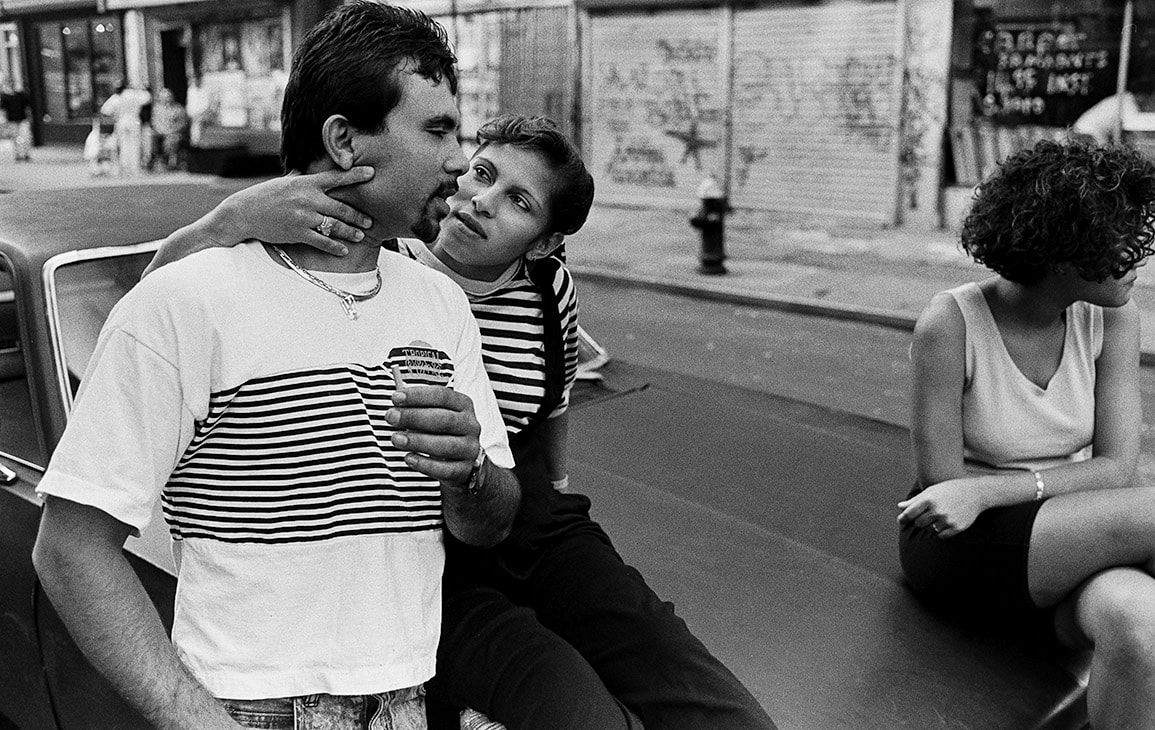

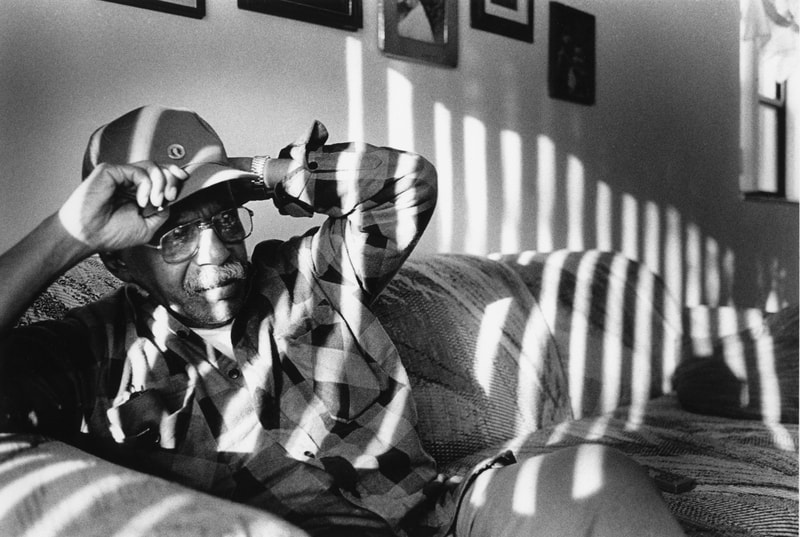

These are two of the chapters in the body of work titled ‘Legal Aliens: Gangsters, Musicians, the Neighborhood.’ The work links two groups of Puerto Rican men; ‘The Ludlow Street Boys’ from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and The East Harlem ‘Old Timers.’ Mainly in New York, I photographed Puerto Rican friends and family over nearly three decades.

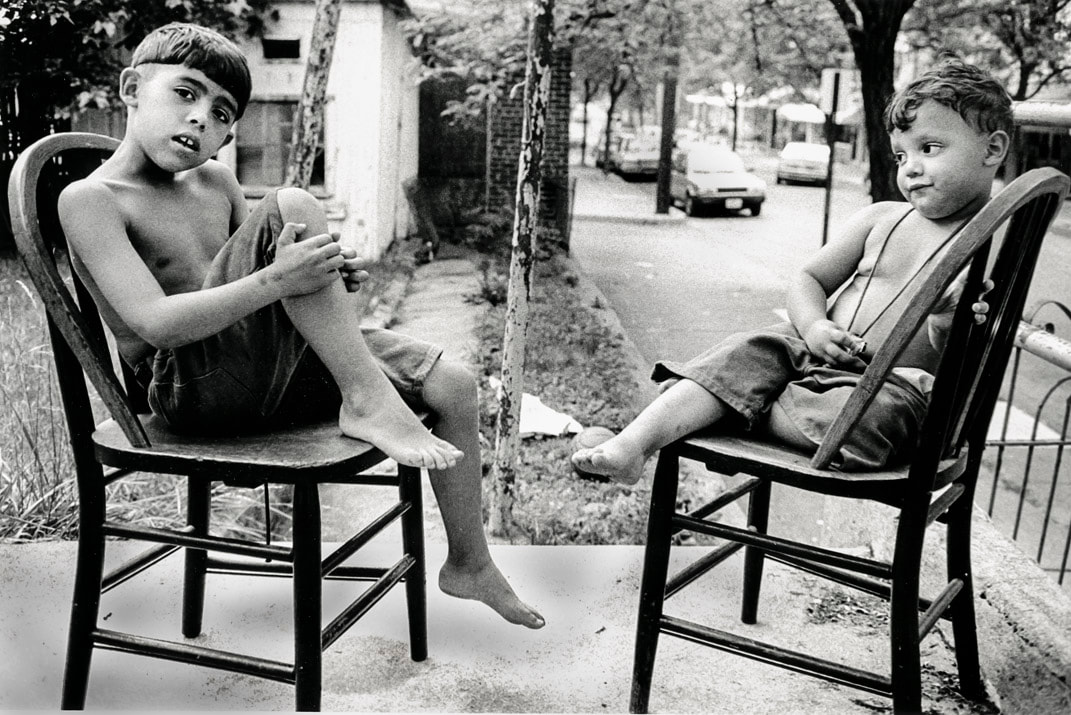

When I moved to Ludlow Street in 1978 there were eight boys and their families living on the block. Fernando, a.k.a. Fern, Eddie a.k.a. Crazy Eddie, David a.k.a. Disco Dave, Jose a.k.a. Pito, Mike a.k.a. Little Man, Tony a.k.a. Tony Tone, Frankie a.k.a. Cabeza and, later, Phil. By the time I started photographing the young men in 1988, two were dead. Tony was murdered in a drug robbery and Frankie choked on his vomit having overdosed when a dealer swapped heroin for cocaine. Despite these odds, many grew up and had families of their own, celebrating birthdays, quinceaneras, graduations, funerals, and the everyday ups and downs.

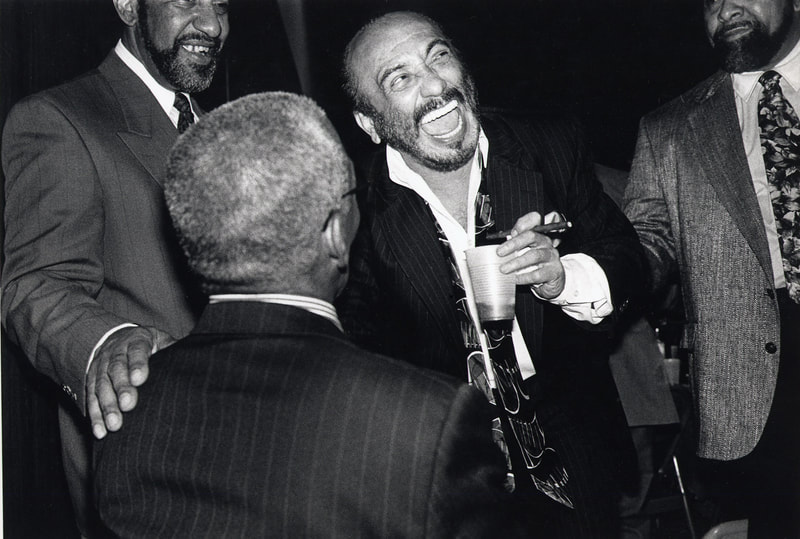

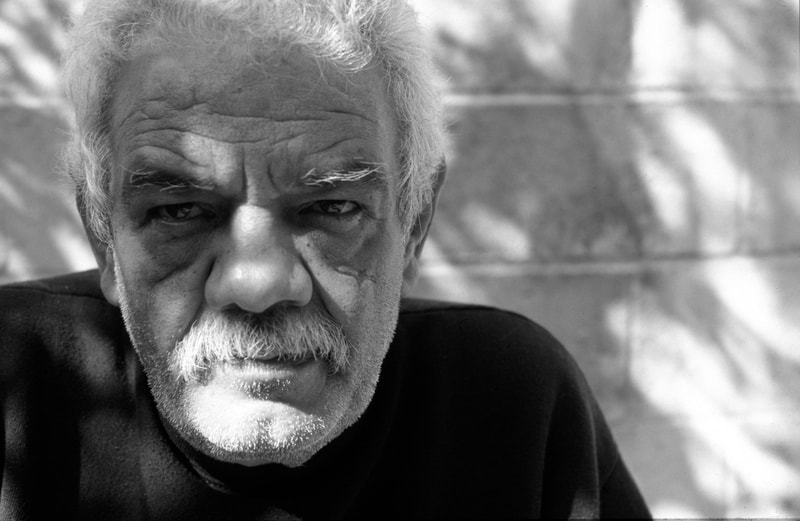

In 1987, I worked as a bartender in salsa clubs and eventually at the Old Timers Lounge in East Harlem. The ‘Old Timers’ came of age in the 1950s. These were the men who fought for the right to walk east of Lexington Avenue when Italian gangs ran the streets. By the time I arrived on the scene many had been in and out of prison for illegal drug dealing. Antonio Roch, a.k.a. Tony Gorilla, was in prison for 40 years and 11 days, including his juvenile time and so he was a cautious ‘OG.’ Over time, I got to know him and his brother Nick Lugo, who once commented that, ‘West Side Story should have been East Side Story.’ Eventually this crew began to invite me to their hangouts and that led to my photographing the huge ballroom dances in Co-Op City and the long standing Latin jazz music series running on Monday nights at the Village Gate.

When I moved to Ludlow Street in 1978 there were eight boys and their families living on the block. Fernando, a.k.a. Fern, Eddie a.k.a. Crazy Eddie, David a.k.a. Disco Dave, Jose a.k.a. Pito, Mike a.k.a. Little Man, Tony a.k.a. Tony Tone, Frankie a.k.a. Cabeza and, later, Phil. By the time I started photographing the young men in 1988, two were dead. Tony was murdered in a drug robbery and Frankie choked on his vomit having overdosed when a dealer swapped heroin for cocaine. Despite these odds, many grew up and had families of their own, celebrating birthdays, quinceaneras, graduations, funerals, and the everyday ups and downs.

In 1987, I worked as a bartender in salsa clubs and eventually at the Old Timers Lounge in East Harlem. The ‘Old Timers’ came of age in the 1950s. These were the men who fought for the right to walk east of Lexington Avenue when Italian gangs ran the streets. By the time I arrived on the scene many had been in and out of prison for illegal drug dealing. Antonio Roch, a.k.a. Tony Gorilla, was in prison for 40 years and 11 days, including his juvenile time and so he was a cautious ‘OG.’ Over time, I got to know him and his brother Nick Lugo, who once commented that, ‘West Side Story should have been East Side Story.’ Eventually this crew began to invite me to their hangouts and that led to my photographing the huge ballroom dances in Co-Op City and the long standing Latin jazz music series running on Monday nights at the Village Gate.

(click on an image to see it larger and view its caption)

Both groups of men represent the implications of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, and the consequences of what Juan Gonzalez calls the Harvest of Empire, a downstream effect of a legacy of colonialism. Because of this continual movement to and from the Island, my relationships in the community took me back to the Island as well. My friend Isa Soto, who I met while working at Tin Pan Alley, invited me to photograph Espiritismo de la Mesa Blanca, while we were both visiting the island.

I started this project as a personal exploration and shot what I could afford. I started with Kodachrome and after building my own darkroom incorporated black and white imagery as it allowed me to share print images with members of my community who had become my second family. As my exhibitions morphed genres, including slide shows with over 200 images set to music, I used hip-hop to depict the Ludlow Boys and salsa for the Old Timers. My intention was to tell these stories as they unfolded and to capture that perpetual motion as authentically as I could.

I started this project as a personal exploration and shot what I could afford. I started with Kodachrome and after building my own darkroom incorporated black and white imagery as it allowed me to share print images with members of my community who had become my second family. As my exhibitions morphed genres, including slide shows with over 200 images set to music, I used hip-hop to depict the Ludlow Boys and salsa for the Old Timers. My intention was to tell these stories as they unfolded and to capture that perpetual motion as authentically as I could.

|

|

Delve deeper |