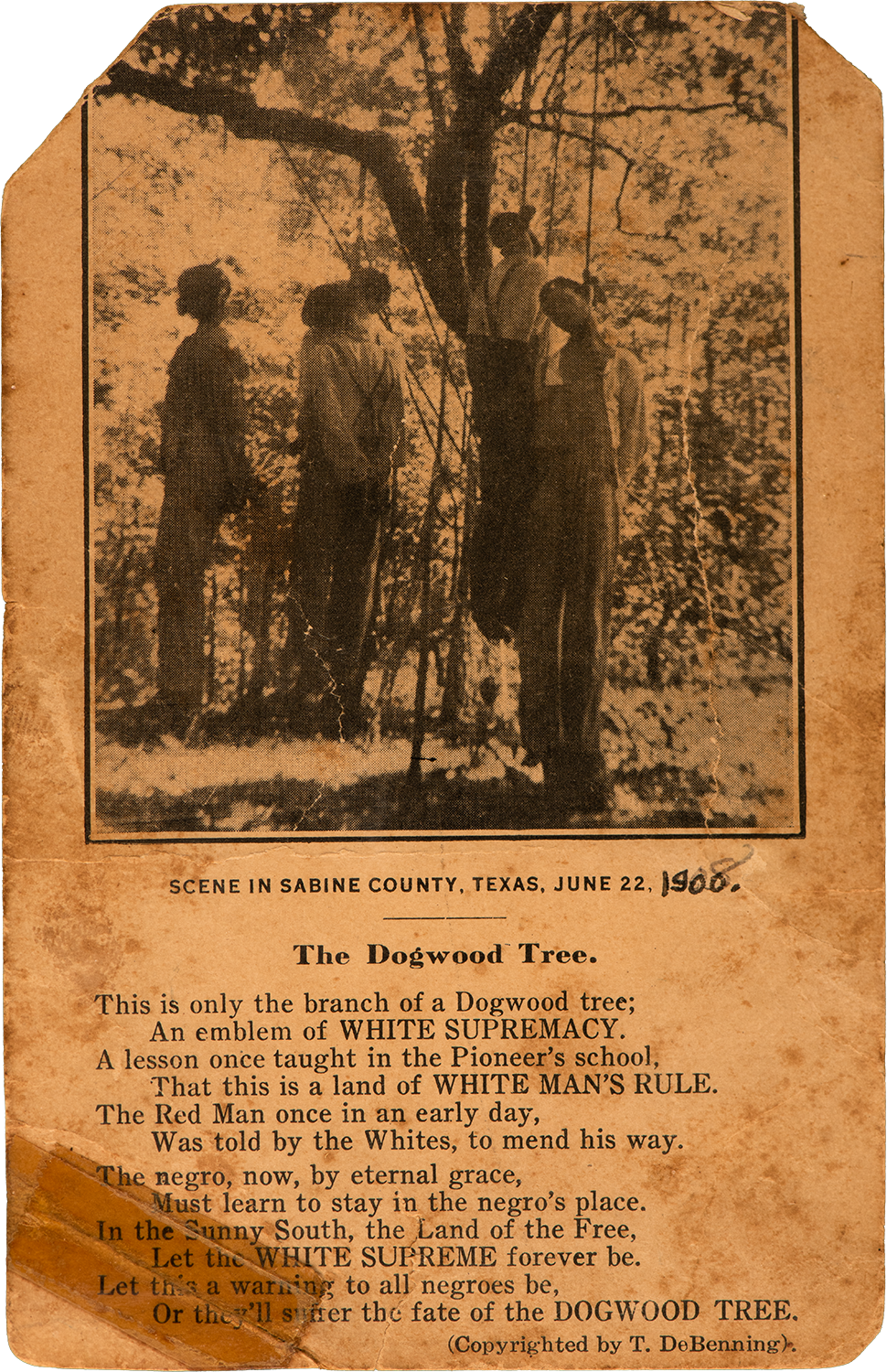

After the Civil War, photographs of lynchings, usually made by unidentified photographers, were published as postcards, often inscribed with racist texts or poems, to be distributed, collected, or kept as souvenirs. The distribution of these postcards through the United States Postal Service was banned in 1908.

The Fort Worth Star Telegram and The Dallas Morning News carried articles on June 23, 1908 from Hemphill, Texas (thirty-five miles northeast of Jasper) about a similar incident. Under the headline, “Mob Hangs Five and Shoots Another,” the Star Telegram reported: "Five negroes, all hanged to one tree, was the spectacle that met the gaze of hundreds of spectators on the Hemphill and Bronson road yesterday about one mile from the court house … They were taken from the Hemphill jail by a determined mob of about 200 men. Six of them in all were taken out, and they were the negroes charged with the murder of Hugh Dean, which occurred at Rockhill church, near Geneva, two weeks ago Saturday night. One of the negroes taken by the mob tried to escape and was shot."

In addition to the newspaper coverage, there was also a photo postcard, published by the Harkrider Drug Co. in nearby Center, Texas, showing the five African American men who were lynched in Sabine County on June 15, 1908 and hung from different limbs of the same dogwood tree. A second printing of this postcard was published with date the June 22, 1908, Copyrighted by T. DeBenning.

Five of the six men who were taken from the jail were identified as “Jerry Evans, aged about 28; Will Johnson, about 20 years; Moss Spellman, about 22 years; Clevel Williams, about 20 years and Will Manuel, 30 years.”

While lynching photographs are inherently racist, the ethics of exhibiting them are complicated. Should they been seen in public, or should they be shrouded? The truth of the images is undeniable. Today, these photo postcards are a stark reminder of the brutality to which African Americans were and are subjected.

The Fort Worth Star Telegram and The Dallas Morning News carried articles on June 23, 1908 from Hemphill, Texas (thirty-five miles northeast of Jasper) about a similar incident. Under the headline, “Mob Hangs Five and Shoots Another,” the Star Telegram reported: "Five negroes, all hanged to one tree, was the spectacle that met the gaze of hundreds of spectators on the Hemphill and Bronson road yesterday about one mile from the court house … They were taken from the Hemphill jail by a determined mob of about 200 men. Six of them in all were taken out, and they were the negroes charged with the murder of Hugh Dean, which occurred at Rockhill church, near Geneva, two weeks ago Saturday night. One of the negroes taken by the mob tried to escape and was shot."

In addition to the newspaper coverage, there was also a photo postcard, published by the Harkrider Drug Co. in nearby Center, Texas, showing the five African American men who were lynched in Sabine County on June 15, 1908 and hung from different limbs of the same dogwood tree. A second printing of this postcard was published with date the June 22, 1908, Copyrighted by T. DeBenning.

Five of the six men who were taken from the jail were identified as “Jerry Evans, aged about 28; Will Johnson, about 20 years; Moss Spellman, about 22 years; Clevel Williams, about 20 years and Will Manuel, 30 years.”

While lynching photographs are inherently racist, the ethics of exhibiting them are complicated. Should they been seen in public, or should they be shrouded? The truth of the images is undeniable. Today, these photo postcards are a stark reminder of the brutality to which African Americans were and are subjected.

|

|

|

|

Curator's note

Alan Govenar

I first heard about this lynching from former Jasper County district attorney Guy James Gray, who prosecuted the white supremacists, who, on June 7, 1998, brutally murdered James Byrd, Jr., by dragging him for three miles behind a pickup truck on an asphalt road. In his interview, Gray described the long history of virulent racial violence in southeast Texas and mentioned that someone had showed him one of these lynching photo postcards. A few weeks later, I was contacted by a man in Beaumont, Texas, who offered to sell Documentary Arts his copy of the June 15, 1908 postcard for $100.

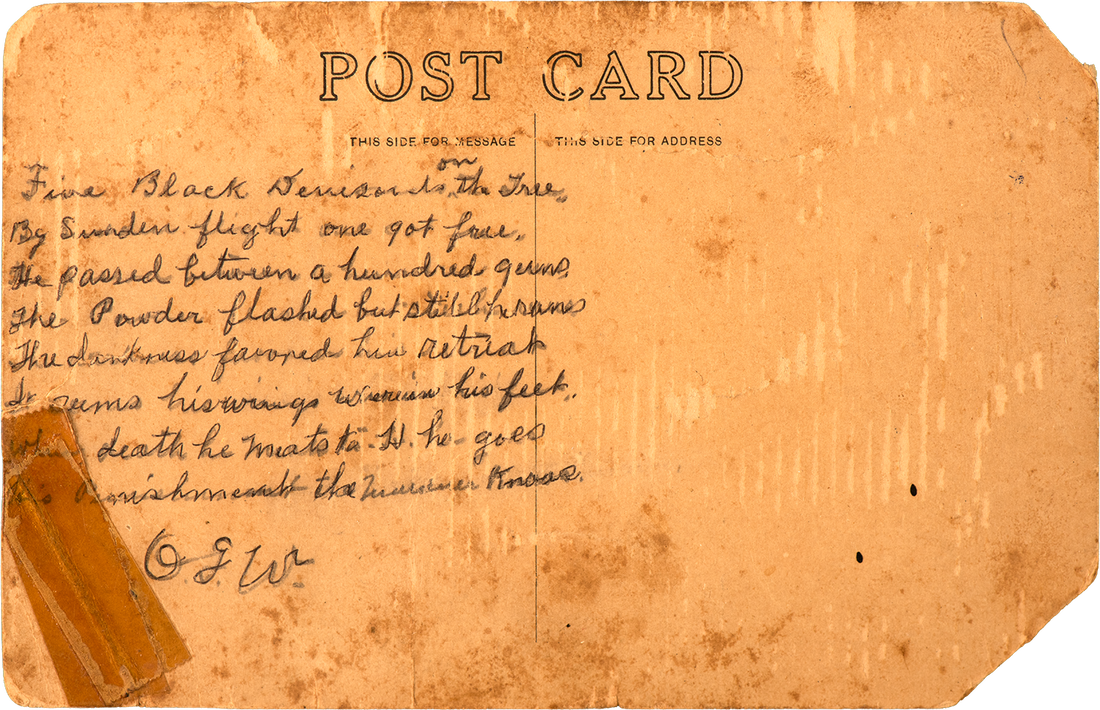

The June 22, 1908 postcard was donated by Bob Ray Sanders, one of Documentary Arts founding board members. Sanders was given the postcard by Shirley Womack, a white woman in Fort Worth. In his column in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sanders wrote, "One day while rummaging through old keepsakes, she ran across a haunting postcard that had been sent to her grandfather by a friend in Sabine County. The card, she remembers, had been passed on to her when she was 10 or 11 years old. By that time, her grandfather had died, and her grandmother had moved out of their home and was living with relatives, she said. To this day, she doesn't know why her mother gave the card to her at that young age, and she has no idea why she kept it or why she never showed it to anyone. Now, she wanted me to see the card to determine whether it should be passed on to someone else for historical purposes. I agreed to take it, and Womack and I met one night at a Fort Worth museum.” The note on the back of the card expressed regret that the friend had missed her grandfather when he was visiting his old hometown. “Say old boy, why didn’t you tell me you was coming,” the friend wrote, “…sorry I didn’t get a chance to see you … Say, look at this picture on the other side and see how they do negros [sic] in this county.”

The June 22, 1908 postcard was donated by Bob Ray Sanders, one of Documentary Arts founding board members. Sanders was given the postcard by Shirley Womack, a white woman in Fort Worth. In his column in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sanders wrote, "One day while rummaging through old keepsakes, she ran across a haunting postcard that had been sent to her grandfather by a friend in Sabine County. The card, she remembers, had been passed on to her when she was 10 or 11 years old. By that time, her grandfather had died, and her grandmother had moved out of their home and was living with relatives, she said. To this day, she doesn't know why her mother gave the card to her at that young age, and she has no idea why she kept it or why she never showed it to anyone. Now, she wanted me to see the card to determine whether it should be passed on to someone else for historical purposes. I agreed to take it, and Womack and I met one night at a Fort Worth museum.” The note on the back of the card expressed regret that the friend had missed her grandfather when he was visiting his old hometown. “Say old boy, why didn’t you tell me you was coming,” the friend wrote, “…sorry I didn’t get a chance to see you … Say, look at this picture on the other side and see how they do negros [sic] in this county.”

Delve Deeper

|

The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions about the Ethics of Viewing

By Parul Sehgal, The New York Times |

|

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America

Book and website |

|

History of Lynchings

Article on the NAACP website |

|

Jasper, Texas

Book by Alan Govenar |

|

“Postcard Offers Look Into Deplorable Past”

Bob Ray Sanders, Fort Worth Star Telegram, April 17, 2005. |

|

“One Episode in Our Tragic History”

Bob Ray Sanders, Fort Worth Star Telegram, April 20, 2005. |