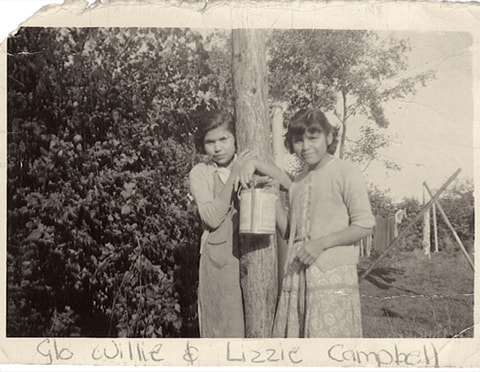

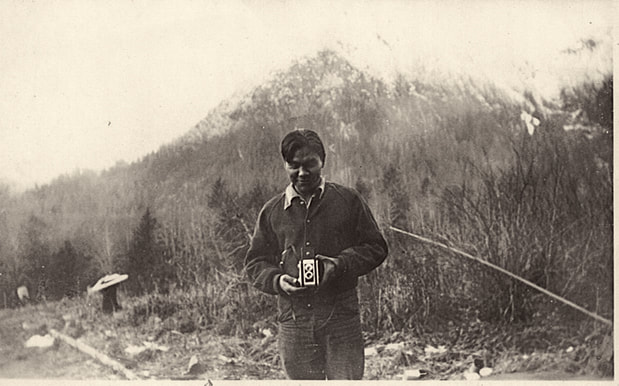

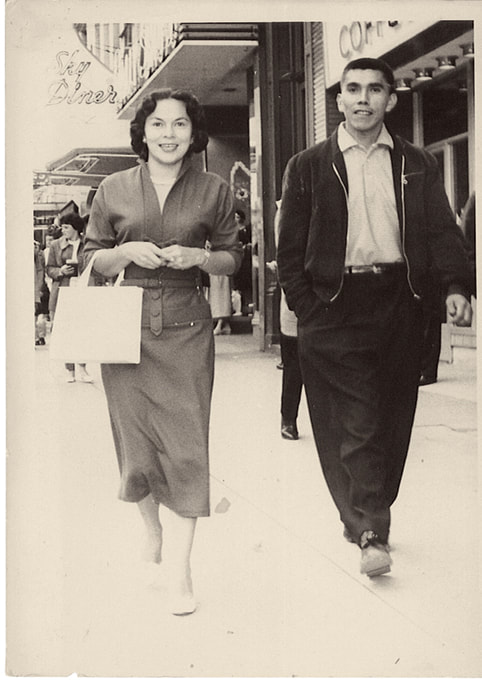

“I was drawn to photography because I was trying to remember. There has been a gap in our transmission of our knowledge, and we used photography as a memory device,” says the artist-activist Marianne Nicolson, who is from the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation community of Kingcome Inlet, in British Columbia. Their three-square-mile reserve is a fraction of the vast territory occupied by the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw prior to colonization, a fate that happened to them specifically and to the broader group of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. A deep regard for the land drives Nicolson to create paintings, monumental pictographs, and light-based installations that incorporate photographs. Her work addresses how the historical political process of treaty making and the contemporary efforts of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada are directly tied to the need for Native peoples to have their land returned.

Nicolson’s glass boxes and panels are adorned with crest symbols of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. Light shines through etched glass, similar to the way light shines through the cedar planks of Kwakwaka’wakw longhouses. These works activate galleries, using the intangible form of light to reference the intangibles of Kwakwaka’wakw culture: songs, stories, and spiritual connections born out of a physical relationship to the land. Dzawada’enuxw symbols of authority and power (bears, lightning, thunderbirds, eagles, rivers, mountains) are projected onto museum walls, challenging the museum industry’s deep investment in promoting the national identities of colonizing nations. Nicolson is taking an activist’s stance, commenting on the Kwakwaka’wakw right to determine the boundaries of their territories and on how that right has been stripped away through the treaty-making process.

Nicolson’s glass boxes and panels are adorned with crest symbols of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. Light shines through etched glass, similar to the way light shines through the cedar planks of Kwakwaka’wakw longhouses. These works activate galleries, using the intangible form of light to reference the intangibles of Kwakwaka’wakw culture: songs, stories, and spiritual connections born out of a physical relationship to the land. Dzawada’enuxw symbols of authority and power (bears, lightning, thunderbirds, eagles, rivers, mountains) are projected onto museum walls, challenging the museum industry’s deep investment in promoting the national identities of colonizing nations. Nicolson is taking an activist’s stance, commenting on the Kwakwaka’wakw right to determine the boundaries of their territories and on how that right has been stripped away through the treaty-making process.

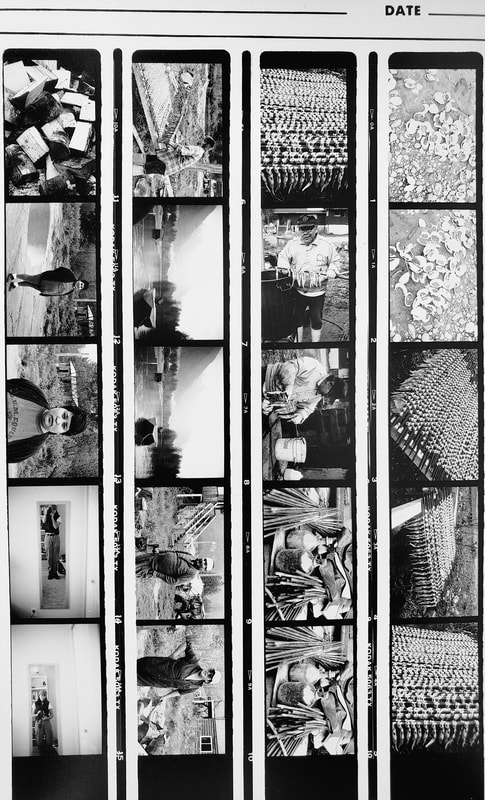

Nearly all of Nicolson’s work references community, the real-world impacts of capitalism, and the ongoing tension felt by Indigenous peoples worldwide in relation to settler colonialism. As a student at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, in the mid-1990s, she would return home to Kingcome Inlet in the summers and capture scenes of everyday life: swimming in the river, preserving fish. These simple activities can now be the cause of land disputes and treaty assertions, particularly if tribal rights to the land or rivers are challenged by private landowners curtailing access to Native communities. Images from this period of fish-filled racks documenting bountiful hooligan fish runs— an event that Nicolson says has not occurred since 2015—are evidence of an ocean previously brimming with abundance.

Nicolson was raised to be a steward of the land, yet she and her community are disempowered by the political processes in the territory now known as Canada. For example, while the Kwakwaka’wakw have intimate knowledge of the declining fish runs due to overfishing, fish farms have been created on their territory without their consent. Nicolson has explored archives and interviewed community elders in order to understand the huge gap in worldviews between Kwakwaka’wakw ways of knowing and the broader society. Her vision is both institutional and personal, based on written records, photographs, and the experiences of community members. “My process is to mine the collections, and make it a living memory,” Nicolson says. “Once you embody it, you don’t need the photograph.”

Even as Nicolson is celebrated by the international art world, she’s wary of what she describes as the “aestheticization of her community’s symbols of power and authority” by mainstream museums. She uses her position to “turn the gaze” back toward the viewing public, attempting to communicate a widely shared Indigenous respect for land, forests, fish, and water. Ultimately, Nicolson sees many of her works as conveying a message of hope—a hope that we recognize the lands and waters as “not just a resource for us to use but as a spirit that has agency.” She challenges viewers to consider how photography can do more than capture a moment. For Indigenous peoples, photography can be used to create living memories which become embodied in the cultural practices of a community. Nicolson’s pieces require our attention, inspire self-reflection, and encourage us to take action—everything you’d expect from an artist whose art practice is rooted in activism.

Nicolson was raised to be a steward of the land, yet she and her community are disempowered by the political processes in the territory now known as Canada. For example, while the Kwakwaka’wakw have intimate knowledge of the declining fish runs due to overfishing, fish farms have been created on their territory without their consent. Nicolson has explored archives and interviewed community elders in order to understand the huge gap in worldviews between Kwakwaka’wakw ways of knowing and the broader society. Her vision is both institutional and personal, based on written records, photographs, and the experiences of community members. “My process is to mine the collections, and make it a living memory,” Nicolson says. “Once you embody it, you don’t need the photograph.”

Even as Nicolson is celebrated by the international art world, she’s wary of what she describes as the “aestheticization of her community’s symbols of power and authority” by mainstream museums. She uses her position to “turn the gaze” back toward the viewing public, attempting to communicate a widely shared Indigenous respect for land, forests, fish, and water. Ultimately, Nicolson sees many of her works as conveying a message of hope—a hope that we recognize the lands and waters as “not just a resource for us to use but as a spirit that has agency.” She challenges viewers to consider how photography can do more than capture a moment. For Indigenous peoples, photography can be used to create living memories which become embodied in the cultural practices of a community. Nicolson’s pieces require our attention, inspire self-reflection, and encourage us to take action—everything you’d expect from an artist whose art practice is rooted in activism.

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America.”

|

|

Delve deeper |