This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the PhotographerAnya Tsaruk is a Ukrainian photographer based in Berlin. Following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, her work now focuses on documenting the consequences of war in her homeland. Through photography, she aims to raise awareness about the war and forced migration as one of its consequences, as well as to honor the resilience and strength of those impacted by it. Tsaruk's work has received several awards and nominations such as Paris Photo: Carte Blanche Students, Fotografia Europea and Skinnerboox Book Award, and The V&A Parasol Foundation Prize for Women in Photography. In addition, her project “Mother Land” has been featured in several group exhibitions, including the Vonovia Photography Award, PEP - Photographic Exploration Project, and Utopias Lahti Visual Arts Festival. |

|

Truth in Photography: Could you talk about your background as a photographer?

Anya Tsaruk: I studied photography in Berlin, at the Neue Schule für Fotografie, which lasted one year from 2021 to 2022. At the end of the year, I started my first long-term project “Mother Land.” Of course, the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine changed my life and had a profound impact on my creative approach. Rather than focusing on my personal career goals, I began perceiving myself, first of all, as a member of the Ukrainian community. My aim is to make a contribution to the Ukrainian cultural heritage, which Russia has tried to destroy, simplify, and assimilate for centuries.

My first impulse was to photograph displaced people at the Berlin train station, but after spending a few days doing that I realized that those pictures lacked individuality. Then I came up with the idea to photograph my mother who fled the war and was staying with me in Berlin. I came home and asked her if she would agree if I take a few photographs of her, and she said yes. I also directly started to involve myself in the pictures, which was very intuitive. We were going through big changes in our relationships as a parent and a child, and my camera helped me to visualize that, first of all for myself.

Anya Tsaruk: I studied photography in Berlin, at the Neue Schule für Fotografie, which lasted one year from 2021 to 2022. At the end of the year, I started my first long-term project “Mother Land.” Of course, the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine changed my life and had a profound impact on my creative approach. Rather than focusing on my personal career goals, I began perceiving myself, first of all, as a member of the Ukrainian community. My aim is to make a contribution to the Ukrainian cultural heritage, which Russia has tried to destroy, simplify, and assimilate for centuries.

My first impulse was to photograph displaced people at the Berlin train station, but after spending a few days doing that I realized that those pictures lacked individuality. Then I came up with the idea to photograph my mother who fled the war and was staying with me in Berlin. I came home and asked her if she would agree if I take a few photographs of her, and she said yes. I also directly started to involve myself in the pictures, which was very intuitive. We were going through big changes in our relationships as a parent and a child, and my camera helped me to visualize that, first of all for myself.

TiP: How old are you now?

Tsaruk: I am 24.

TiP: We have been publishing the images of Maxim Dondyuk of the war in Ukraine. It is a genocide that is happening there.

Tsaruk: It is not simply happening there, it is Russia who is committing genocide in Ukraine. That's very important to name the aggressor. Many western media still call the Russian war in Ukraine “the Ukraine crisis” or “conflict,” which is wrong on many levels, as the way we name things directly influences the way we perceive them.

TiP: Without this kind of visualization of it, people won't know. It's like what happened in Nazi Germany. If the photographs didn't exist, people would not have known what really happened.

Tsaruk: There is a big temptation to look away, especially when it doesn't touch you or your family, but you shouldn't. It is very hard and painful, but it is the reality. There are also multiple ways of showing war, and all of them have their place in forming our perception of the events. My project explores universal questions, such as the mother-daughter relationship, the meaning of home, identity, and belonging through the prism of the war. By focusing on my personal story, on my feelings, I aim to convey the experience of the war in my homeland in a way that is relatable and empathetic.

TiP: Could you complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”

Tsaruk: Truth in photography is the experience of the photographer. Viewers can relate to it in their own way and discover their own truth. Photography, and art in general, has the power to raise questions and invite reflection, challenging the viewer to think critically about their own beliefs and experiences.

TiP: How does your work express what's happening in Ukraine? What are you trying to convey through your photographs? Because there is a certain formalistic quality to them. There's a certain calm that you see in the photographs.

Tsaruk: Through “Mother Land,” I've not only captured my own story, but also shed light on the experiences of many other families affected by the war. Millions of people had to leave their homes, loved ones, dreams, and expectations, and to move somewhere they've never been, forcibly, and try to build their life there. There are a lot of stories like this. Many of my friends started to live with their parents again, mostly their mothers, because only women were allowed to leave the country, and so certain dynamics in those relationships were evolving.

My mom and I, we changed a lot. The unexpected circumstances we found ourselves in, forced us to really get to know each other. Before, I would come to Ukraine once in a year and would be a perfect daughter. Now mom was coming to my house, to my territory, and no one knew how long it will last. So “Mother Land” is also a story about growing up.

TiP: How do you express that? How do you show that in your photographs?

Tsaruk: I think that this switch of roles is visible in the pictures. For example, our portrait where I sit in the back, and she sits in front. Usually, in portraits, children sit in front and parents in the back. So here, the story begins with her coming into my house and me taking care of her.

Tsaruk: I am 24.

TiP: We have been publishing the images of Maxim Dondyuk of the war in Ukraine. It is a genocide that is happening there.

Tsaruk: It is not simply happening there, it is Russia who is committing genocide in Ukraine. That's very important to name the aggressor. Many western media still call the Russian war in Ukraine “the Ukraine crisis” or “conflict,” which is wrong on many levels, as the way we name things directly influences the way we perceive them.

TiP: Without this kind of visualization of it, people won't know. It's like what happened in Nazi Germany. If the photographs didn't exist, people would not have known what really happened.

Tsaruk: There is a big temptation to look away, especially when it doesn't touch you or your family, but you shouldn't. It is very hard and painful, but it is the reality. There are also multiple ways of showing war, and all of them have their place in forming our perception of the events. My project explores universal questions, such as the mother-daughter relationship, the meaning of home, identity, and belonging through the prism of the war. By focusing on my personal story, on my feelings, I aim to convey the experience of the war in my homeland in a way that is relatable and empathetic.

TiP: Could you complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”

Tsaruk: Truth in photography is the experience of the photographer. Viewers can relate to it in their own way and discover their own truth. Photography, and art in general, has the power to raise questions and invite reflection, challenging the viewer to think critically about their own beliefs and experiences.

TiP: How does your work express what's happening in Ukraine? What are you trying to convey through your photographs? Because there is a certain formalistic quality to them. There's a certain calm that you see in the photographs.

Tsaruk: Through “Mother Land,” I've not only captured my own story, but also shed light on the experiences of many other families affected by the war. Millions of people had to leave their homes, loved ones, dreams, and expectations, and to move somewhere they've never been, forcibly, and try to build their life there. There are a lot of stories like this. Many of my friends started to live with their parents again, mostly their mothers, because only women were allowed to leave the country, and so certain dynamics in those relationships were evolving.

My mom and I, we changed a lot. The unexpected circumstances we found ourselves in, forced us to really get to know each other. Before, I would come to Ukraine once in a year and would be a perfect daughter. Now mom was coming to my house, to my territory, and no one knew how long it will last. So “Mother Land” is also a story about growing up.

TiP: How do you express that? How do you show that in your photographs?

Tsaruk: I think that this switch of roles is visible in the pictures. For example, our portrait where I sit in the back, and she sits in front. Usually, in portraits, children sit in front and parents in the back. So here, the story begins with her coming into my house and me taking care of her.

Then, the picture where I smoke a cigarette in the kitchen. It's also this gesture that I'm a grown-up and smoking, which my mom doesn't like. I still do it, because it's my house and my rules.

This photograph, the door handle, is the beginning of my mother's own story in Berlin, where she moves to the separate apartment. She becomes more independent and has her own life here. There are photographs where she takes care of me. She's holding my hand, or she braids my hair, which she would always do when I was a child. You can see her own steps in forming her surrounding and routine. And in the end, she takes this role of mother back when she sings me a lullaby and I'm trying to fall asleep. It is the same act as in my childhood, but now it is different, we are different.

TiP: How do you convey in your photographs the pain, the suffering, and the fear? How is that visible, or is it visible?

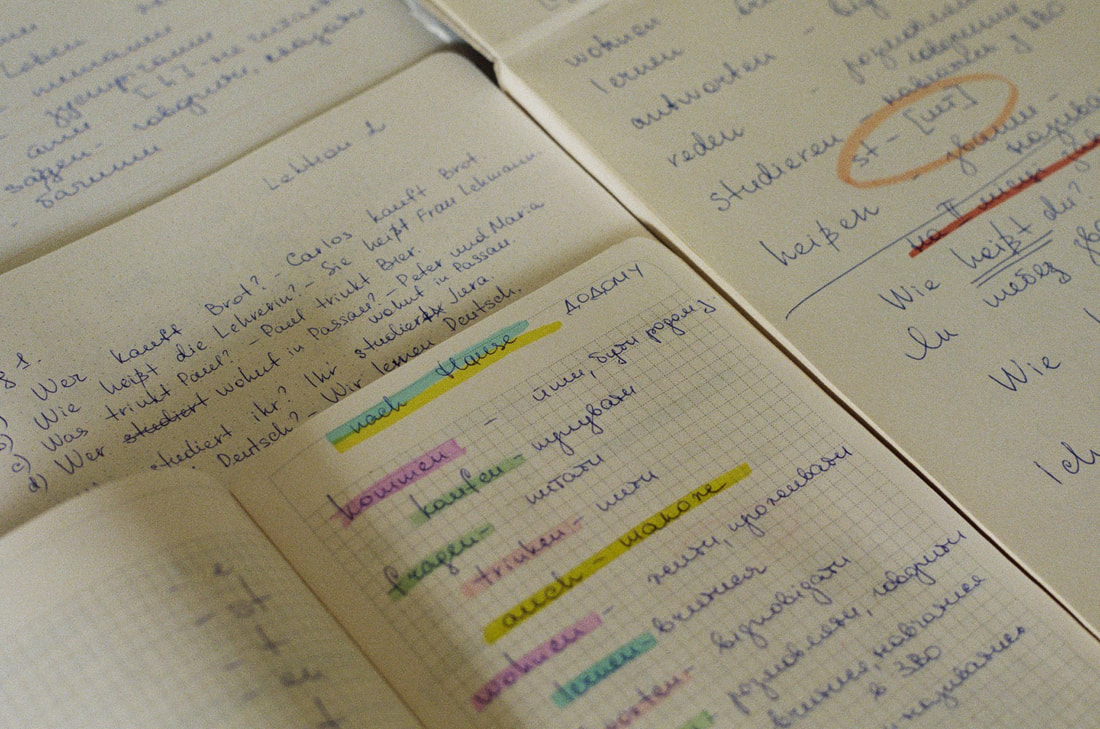

Tsaruk: I would say it is. It's a lot about those feelings. Like the photographs in the church and of her singing, as well as in her German language workbook where she wrote “nach Hause,” or “home” in German, and painted in the colors of the Ukrainian flag. It's all those details, or the flag ribbon she put on the door handle when she moved into the separate apartment. That's how she marked this place. This feeling of being physically here, but still trying to process what is happening back in Ukraine.

Tsaruk: I would say it is. It's a lot about those feelings. Like the photographs in the church and of her singing, as well as in her German language workbook where she wrote “nach Hause,” or “home” in German, and painted in the colors of the Ukrainian flag. It's all those details, or the flag ribbon she put on the door handle when she moved into the separate apartment. That's how she marked this place. This feeling of being physically here, but still trying to process what is happening back in Ukraine.

TiP: What does home mean to you?

Tsaruk: Ukraine. It’s my history. It's my mom's lullabies. It's the culture I belong to. And that's something I’m rediscovering now. I moved out of Ukraine when I was seventeen, because I had the feeling that in order to succeed, I had to move out. This is the perspective of our country that Russia imposed on us. That as a colonized country, you are not as good as the colonizer. So, you either have to go to Moscow, or you have to go to Europe. But this terrible year has really changed such a perception. I realized that I never really explored my own culture. I would travel abroad, I would try to understand the world by looking outside, but not inside myself and my country. And that's the first step. Outside doesn't have any meaning if you don't know your own culture, your roots, and the history of your family. That's something I think a lot about now and I feel really guilty for not realizing that before. Something I discovered about myself is a strong connection with my homeland which is always inside me, even when I’m very far away from there.

TiP: Why did you choose to include your mother's songs in your work?

Tsaruk: On the first day of the Russian full-scale invasion, being numb, shocked, and terrified, I felt a strong need to hear my mom's lullaby. Holding back tears, she sang it to me on the phone. At the moment, when it felt like the world was collapsing, only her voice was able to calm me down. It was very, very emotional.

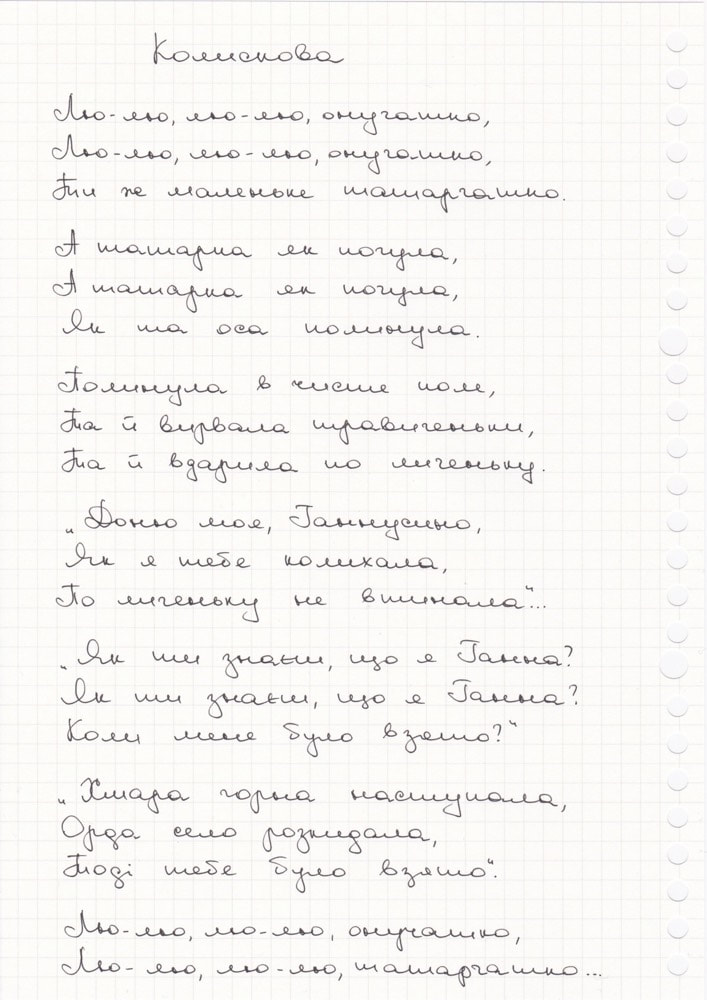

My mom is a singing teacher, and Ukrainian folk songs were a big part of my childhood. Every evening, she would sing as many lullabies as years I was until the age of five, when I asked her to not sing to me anymore.

I wanted to record her voice, and her songs, and also to preserve them from disappearing. Most of them are not very well-known Ukrainian songs, and some are very local, from my region. We recorded 15 songs, and five of them became a part of the project.

As I started to think about my national self-identity and what my association with Ukraine is, I realized that my mom's songs are in a way something that formed my love for Ukraine. Also, the song is one of the cultural elements in which people try to process their feelings. When they want to express joy or pain, they sit down and sing. In Ukraine, it's a big thing, and I want to preserve this heritage.

Those songs are about the love of people for their country, about the love of mothers for their daughters, and about love as such. And nowadays they gain a new meaning for me and for millions of Ukrainians.

Tsaruk: Ukraine. It’s my history. It's my mom's lullabies. It's the culture I belong to. And that's something I’m rediscovering now. I moved out of Ukraine when I was seventeen, because I had the feeling that in order to succeed, I had to move out. This is the perspective of our country that Russia imposed on us. That as a colonized country, you are not as good as the colonizer. So, you either have to go to Moscow, or you have to go to Europe. But this terrible year has really changed such a perception. I realized that I never really explored my own culture. I would travel abroad, I would try to understand the world by looking outside, but not inside myself and my country. And that's the first step. Outside doesn't have any meaning if you don't know your own culture, your roots, and the history of your family. That's something I think a lot about now and I feel really guilty for not realizing that before. Something I discovered about myself is a strong connection with my homeland which is always inside me, even when I’m very far away from there.

TiP: Why did you choose to include your mother's songs in your work?

Tsaruk: On the first day of the Russian full-scale invasion, being numb, shocked, and terrified, I felt a strong need to hear my mom's lullaby. Holding back tears, she sang it to me on the phone. At the moment, when it felt like the world was collapsing, only her voice was able to calm me down. It was very, very emotional.

My mom is a singing teacher, and Ukrainian folk songs were a big part of my childhood. Every evening, she would sing as many lullabies as years I was until the age of five, when I asked her to not sing to me anymore.

I wanted to record her voice, and her songs, and also to preserve them from disappearing. Most of them are not very well-known Ukrainian songs, and some are very local, from my region. We recorded 15 songs, and five of them became a part of the project.

As I started to think about my national self-identity and what my association with Ukraine is, I realized that my mom's songs are in a way something that formed my love for Ukraine. Also, the song is one of the cultural elements in which people try to process their feelings. When they want to express joy or pain, they sit down and sing. In Ukraine, it's a big thing, and I want to preserve this heritage.

Those songs are about the love of people for their country, about the love of mothers for their daughters, and about love as such. And nowadays they gain a new meaning for me and for millions of Ukrainians.

TiP: This is your first major photographic project. How do you envision the relationship of the music to the stories? Because your photographs are largely symbolic. If you didn't have some text to accompany your photographs, they might be difficult to understand. Do you feel that way?

Tsaruk: Yes. Now I'm working on the photobook with the great Ukrainian artist Katya Lesiv, and we envision it having very short texts next to the photographs, which would be very literal, but without interpreting what's in the pictures. Regarding the music, I don’t want the photographs and the songs fighting for being the main element of the project. I see the songs as a background for the photographs, a framework for the story to be built.

Tsaruk: Yes. Now I'm working on the photobook with the great Ukrainian artist Katya Lesiv, and we envision it having very short texts next to the photographs, which would be very literal, but without interpreting what's in the pictures. Regarding the music, I don’t want the photographs and the songs fighting for being the main element of the project. I see the songs as a background for the photographs, a framework for the story to be built.

|

|

Sleep my grandchild, sleep tight,

Sleep my grandchild, sleep tight, You’re my little Tatar, my light. And a Tatar once that heard, And a Tatar once that heard, She flew away like a bird. To the open field she flew, And she picked a bunch of herbs, And she slapped her on the face. “My dear daughter, Hannusyna, As I cradled you, embraced, Never did I slap you on the face.” “How do you know: I’m Hanna? How do you know: I’m Hanna? When was I then taken?” “Dark cloud was coming, The horde was attacking, And then you were taken.” Sleep my grandchild, sleep tight, Sleep my little Tatar, my light. Translated into English by Tania Rodionova Press to listen |

TiP: Do you feel that you need words to help to explain the truth of the image?

Tsaruk: It's not about the explanation. Those very literal quotes add another layer to the perception of the work. I'm not explaining the story behind the photograph, but complementing it.

TiP: What do you want people to feel when they look at your photographs?

Tsaruk: I want people to think of their mother and their childhood, to think of the land which they connect themselves with, their roots. It's not only the story about my mom, but also an invitation for the audience to reflect on their own identity and belonging, the feelings to their own mother or their own daughter.

Tsaruk: It's not about the explanation. Those very literal quotes add another layer to the perception of the work. I'm not explaining the story behind the photograph, but complementing it.

TiP: What do you want people to feel when they look at your photographs?

Tsaruk: I want people to think of their mother and their childhood, to think of the land which they connect themselves with, their roots. It's not only the story about my mom, but also an invitation for the audience to reflect on their own identity and belonging, the feelings to their own mother or their own daughter.

TiP: It’s an amazing time for photobooks. It's an amazing medium of expression.

Tsaruk: Yes. I think that a photobook creates a space for a very intimate connection with the work, which is not always possible at the exhibition. When you can take your time to look at the photographs, listen to the music, read the lyrics, and touch the paper. It's also important for me to give the access to the story in places where this access is not possible through the exhibition.

TiP: How many people from Ukraine do you think now live in Berlin?

Tsaruk: Quite a lot. I don't know the numbers, but you can hear the language quite often and there are a lot of cultural events, exhibitions, film festivals, parties, and community gatherings organized by Ukrainians and for Ukrainians.

TiP: Why did you go to Berlin?

Tsaruk: I moved here three years ago, and it just seemed like a place to be — very free and accepting in a lot of ways. I was just fresh off my studies and got an internship here. Back then I had the feeling that I could go anywhere and do anything.

TiP: Do you think about ever moving back to Ukraine?

Tsaruk: In the near future, no. Ukraine is my dearest country and it's my home, but I’d miss the diversity that I have here in Berlin. I'm used to this very international circle of people with different backgrounds. But for a shorter time, of course, I am planning to do some projects in Ukraine.

TiP: It's difficult to think about going back to a place that will almost be unrecognizable.

Tsaruk: I am absolutely sure that we will rebuild Ukraine. Our nation and our people changed so much this year. We realized so many things! Our politics are changing as well, the level of social awareness and solidarity is impressive. I have a very strong belief in a prosperous, free, young, and progressive Ukraine, which should come, which will come, and which we are creating. Someone being there, someone being abroad, everyone has their own place, and everyone has their own role in this mission. I believe in my country.

Tsaruk: Yes. I think that a photobook creates a space for a very intimate connection with the work, which is not always possible at the exhibition. When you can take your time to look at the photographs, listen to the music, read the lyrics, and touch the paper. It's also important for me to give the access to the story in places where this access is not possible through the exhibition.

TiP: How many people from Ukraine do you think now live in Berlin?

Tsaruk: Quite a lot. I don't know the numbers, but you can hear the language quite often and there are a lot of cultural events, exhibitions, film festivals, parties, and community gatherings organized by Ukrainians and for Ukrainians.

TiP: Why did you go to Berlin?

Tsaruk: I moved here three years ago, and it just seemed like a place to be — very free and accepting in a lot of ways. I was just fresh off my studies and got an internship here. Back then I had the feeling that I could go anywhere and do anything.

TiP: Do you think about ever moving back to Ukraine?

Tsaruk: In the near future, no. Ukraine is my dearest country and it's my home, but I’d miss the diversity that I have here in Berlin. I'm used to this very international circle of people with different backgrounds. But for a shorter time, of course, I am planning to do some projects in Ukraine.

TiP: It's difficult to think about going back to a place that will almost be unrecognizable.

Tsaruk: I am absolutely sure that we will rebuild Ukraine. Our nation and our people changed so much this year. We realized so many things! Our politics are changing as well, the level of social awareness and solidarity is impressive. I have a very strong belief in a prosperous, free, young, and progressive Ukraine, which should come, which will come, and which we are creating. Someone being there, someone being abroad, everyone has their own place, and everyone has their own role in this mission. I believe in my country.

Mother Land, film by Anya Tsaruk

|

|

Delve deeper |