|

|

What can artists, archivists, and communities learn from historic collections of Native photography? |

|

|

INTERVIEW

by Wendy Red Star I met Emily Moazami in October of 2018 during my Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship in Washington, D.C. It was my first time in the capital and my first experience working with the Smithsonian museums. My initial goal was to research Apsáalooke (Crow) delegations using the photography archives and material objects at the National Museum of the American Indian, the National Anthropological Archives, and the National Museum of Natural History. Emily, assistant head archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Archive Center, not only produced material pertaining to my research topic but led me to discover a personal connection—a direct link to my ancestors whose images and artifacts are housed in the museum.

In this conversation, Emily and I discuss the photography collections of the National Museum of the American Indian and some of my discoveries from my research, as well as questions about the care of these precious materials. We also talk about the importance of collaboration between communities and institutions in building connections that strengthen the collective knowledge and history of the Archive Center’s holdings. |

Wendy Red Star: The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) has a vast collection. But a lot of these images don’t have identification when it comes to Native people. What is your process at the museum for identifying Native people?

Emily Moazami: Unfortunately, a lot of photographers didn’t record the names of Native peoples because they saw them as archetypes of noble savages and a dying race. We are working hard to repersonalize these images and add people’s names to the archival records. Many identifications actually come from descendants of the people depicted. When we have visitors to the archives looking through photographs, we’ll get identifications that way. Or somebody who is not related but from the community recognizes someone.

Red Star: Besides community members, what other resources are used as important measures for identification?

Moazami: Sometimes it will come from an anthropologist’s field notes. An anthropologist goes into a community, and he photographs the people there, he collects objects, and he takes notes. Other times, it might come from a researcher who has worked with a particular community often. As a photo archivist, you tend to recognize people’s faces if you’re researching a particular community a lot. We also get identifications from other institutions’ records.

Red Star: What about professional photographs?

Moazami: Yes, for example, if somebody sat for a delegation photograph taken when Native representatives were meeting with government officials, the image would be clearly documented with the person’s name, so then if you find an amateur photographer’s photograph of that same person, you might be able to match it up that way.

Red Star: What happens if different community members have different identifications, or if someone can’t be identified at all? Then what?

Moazami: If someone identifies a person, and later someone else comes along and says, “No, the first identification is wrong,” then what we’ll often do is put both names in the catalog records. We always put the source of that information in an internal note in our database. That way, in the future, if someone shows up at the archives and says, “How do you know it’s this person?” we can trace back to where we got the information in the first place.

But, unfortunately, there are a lot of people in the photographs who may never be identified, and as generations pass on, we lose that opportunity to work with people who have that knowledge. So really, time is of the essence.

Emily Moazami: Unfortunately, a lot of photographers didn’t record the names of Native peoples because they saw them as archetypes of noble savages and a dying race. We are working hard to repersonalize these images and add people’s names to the archival records. Many identifications actually come from descendants of the people depicted. When we have visitors to the archives looking through photographs, we’ll get identifications that way. Or somebody who is not related but from the community recognizes someone.

Red Star: Besides community members, what other resources are used as important measures for identification?

Moazami: Sometimes it will come from an anthropologist’s field notes. An anthropologist goes into a community, and he photographs the people there, he collects objects, and he takes notes. Other times, it might come from a researcher who has worked with a particular community often. As a photo archivist, you tend to recognize people’s faces if you’re researching a particular community a lot. We also get identifications from other institutions’ records.

Red Star: What about professional photographs?

Moazami: Yes, for example, if somebody sat for a delegation photograph taken when Native representatives were meeting with government officials, the image would be clearly documented with the person’s name, so then if you find an amateur photographer’s photograph of that same person, you might be able to match it up that way.

Red Star: What happens if different community members have different identifications, or if someone can’t be identified at all? Then what?

Moazami: If someone identifies a person, and later someone else comes along and says, “No, the first identification is wrong,” then what we’ll often do is put both names in the catalog records. We always put the source of that information in an internal note in our database. That way, in the future, if someone shows up at the archives and says, “How do you know it’s this person?” we can trace back to where we got the information in the first place.

But, unfortunately, there are a lot of people in the photographs who may never be identified, and as generations pass on, we lose that opportunity to work with people who have that knowledge. So really, time is of the essence.

|

Red Star: When it came to that supposed image of my great-grandfather Red Star, I tried to figure out if it was him by going through the censuses. But the date of when that photograph was taken indicated that he would have been a middle-aged man and not a child. I thought maybe it could be my grandfather Wallace Red Star Sr. Then I found that same image in the National Anthropological Archives with the child labeled as Sidney Black Hair. How do some images end up in multiple archives across the country, and how can researchers approach tracking down their sources from various collections?

Moazami: It’s the nature of photographs and how they’re shared. Professional photographers made prints and scattered them around. Amateur photographers may have sent some of the photographs to family members or friends. Many of these professional and amateur photographs were then donated to museums, so you get the same image at multiple institutions. |

As a researcher, it’s important to think of the context and consider why and where the photographs were shot. Especially the question of why. If it was a professional photographer, or if they were working for a government institution, that could help you track down where the negatives ended up. For example, if it was a delegation portrait, it might end up in the National Anthropological Archives or the National Archives and Records Administration.

Many institutions, such as NMAI, are putting their collections online. Now you can more easily search and find these connections, either the same photograph or a similar photograph that was part of a set.

Red Star: Making the artwork that I make, using historical images, I’ve seen on social media the popularity of historical images of Native people. A lot of them come from Pinterest. What are the effects of sharing these images, and does this influence the work that you’re doing in the archives?

Moazami: I’m torn, because I can imagine, let’s say, there is a Native teenager who happens to stumble across some of these photographs, and they really inspire them, and maybe they didn’t know these photographs existed of their tribe. So in that way, I think it could be really wonderful. I’m assuming a lot of teenagers are not sitting around searching our collections online, so maybe that’s a way to get them interested. But I get frustrated that people don’t always link back to the original source.

Red Star: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

Moazami: I went through our catalog records to see what photographers we had who were photographing in the region. I also looked at other institutions’ catalog records—for example, the National Anthropological Archives—to find photographs that were taken in the region of the Apsáalooke peoples. There are also some great resources, like biographical dictionaries, that list photographers by state. I looked in the section for Montana, and I saw which photographers were listed as having photographed in the region.

Red Star: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

Many institutions, such as NMAI, are putting their collections online. Now you can more easily search and find these connections, either the same photograph or a similar photograph that was part of a set.

Red Star: Making the artwork that I make, using historical images, I’ve seen on social media the popularity of historical images of Native people. A lot of them come from Pinterest. What are the effects of sharing these images, and does this influence the work that you’re doing in the archives?

Moazami: I’m torn, because I can imagine, let’s say, there is a Native teenager who happens to stumble across some of these photographs, and they really inspire them, and maybe they didn’t know these photographs existed of their tribe. So in that way, I think it could be really wonderful. I’m assuming a lot of teenagers are not sitting around searching our collections online, so maybe that’s a way to get them interested. But I get frustrated that people don’t always link back to the original source.

Red Star: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

Moazami: I went through our catalog records to see what photographers we had who were photographing in the region. I also looked at other institutions’ catalog records—for example, the National Anthropological Archives—to find photographs that were taken in the region of the Apsáalooke peoples. There are also some great resources, like biographical dictionaries, that list photographers by state. I looked in the section for Montana, and I saw which photographers were listed as having photographed in the region.

Red Star: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

|

Moazami: I went through our catalog records to see what photographers we had who were photographing in the region. I also looked at other institutions’ catalog records—for example, the National Anthropological Archives—to find photographs that were taken in the region of the Apsáalooke peoples. There are also some great resources, like biographical dictionaries, that list photographers by state. I looked in the section for Montana, and I saw which photographers were listed as having photographed in the region.

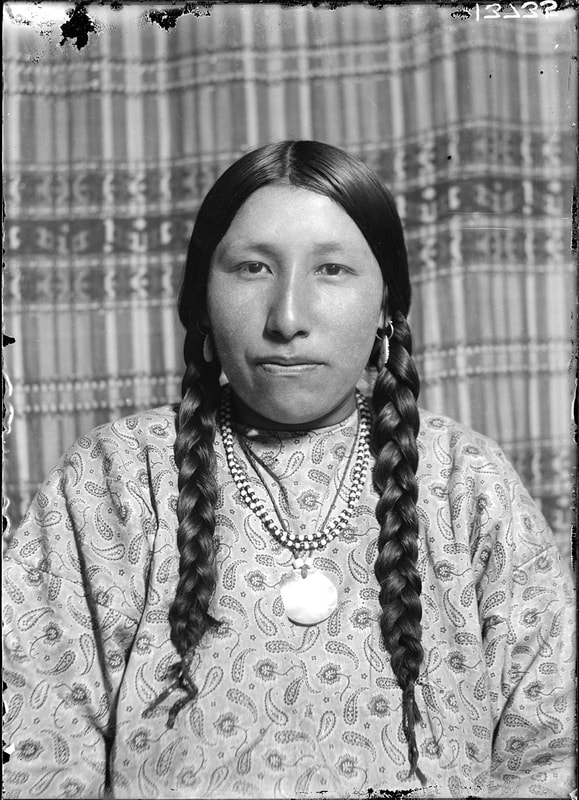

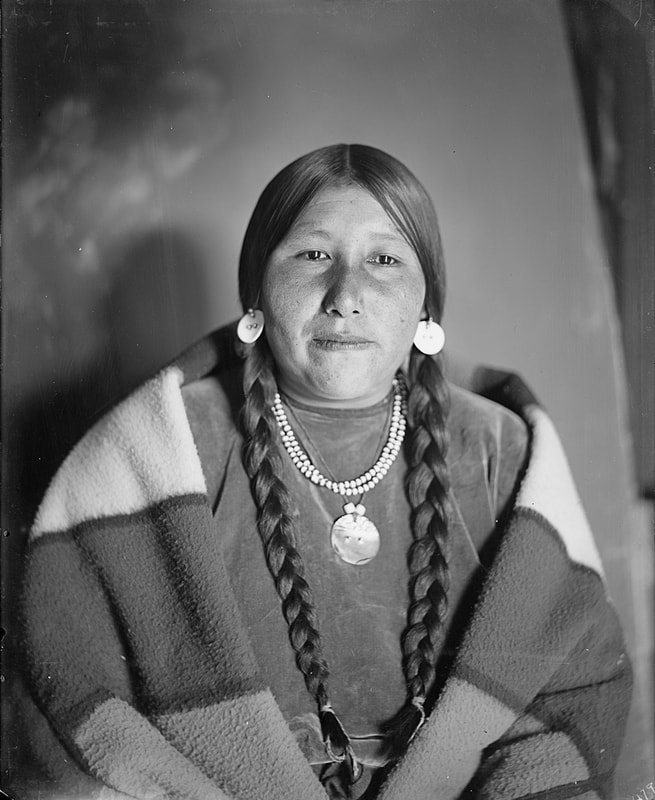

Red Star: When you were showing me photographs that Fred E. Miller took in the early 1900s, one of the images happened to be of my great-great-grandmother Her Dreams Are True, or I’ve also seen her name written as Dreams The Truth—her English name is Julia Bad Boy, which is an excellent name. I was thrilled, because it’s such a beautiful photograph. She’s sitting in front of this striped background—you can tell it’s a weaving of some sort—that really sets off her paisley-style underdress. We found another photograph, of two Crow men with the same background, noting that it was taken at the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, in Crow Agency, Montana. That gave me the location of where my great-great-grandmother’s photograph was taken. After I finished my research at NMAI, I had a printout of that image of Her Dreams Are True. I decided I should look into another photographer named Richard Throssel, who was also photographing my community around the same time, to see if he took a picture of my great-great grandmother. I researched his archive, and I found a portrait of her. I was so excited. It looks like she’s a few years older in the Throssel photograph. It somehow felt spiritual to find her. Moazami: That’s incredible to have that connection. |

Red Star: Let’s talk about the importance of amateur or noncommercial photographers who contributed to the historical record of Native people—like Miller, who held various governmental positions at the Crow reservation, and Throssel, who also worked for Indian Services.

Moazami: Many of the technological advances in the field of photography coincided with the westward expansion of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was also a period of transition for Native people, who were forced from their traditional homelands and made to live on reservations.

All of a sudden, you had these anthropologists and missionaries and government employees, and even teachers, and they were all grabbing these easy-to-use, handheld cameras with dry plate negatives and, later, film negatives to document their time working with Native communities. Many times, they might have documented it to show their success, for example, at assimilating Native peoples. Though Fred E. Miller, I do believe, was just documenting his life and the people around him. Miller was trained as a photographer; however, he was working with the Crow in the capacity of a government employee rather than that of a commercial photographer. Throssel did some work as a photographer for the Office of Indian Affairs.

Red Star: Yes, Miller and Throssel, who both worked for Indian Services on the Crow reservation, also took personal photographs of regular life on the reservation, gaining the trust of the community to photograph some of their intimate events.

Moazami: Consequently, these photographs give you a glimpse of what everyday life might have been like for various Native communities. You get photographs that document not only chiefs and leaders in the community but also women and men and children, the people who didn’t have the opportunity to go to photography studios.

With studio portraiture, people would always dress up in their best outfits, and they would be posed. Often a photographer would give Native individuals props to make them look like a stereotypical Indian, an archetype. With amateur and candid photographs, you’ve got people wearing their everyday clothing, going about their daily chores, making food for their families. Many amateur photographs were not widely published or circulated; they’re incredibly rare, whereas with Edward Curtis, his photographs are represented in every repository.

Red Star: Curtis also photographed my community, but I love the Throssel and Miller images more. Maybe because the community really trusted them. Throssel’s portraits of women are extraordinary, so powerful and dignified, really at the forefront of his imagery, whereas I feel like Curtis mainly focused on chiefs and warriors and scouts and things like that. In the Miller and Throssel photographs, it was nice to see some of the camp images of women beading or cooking, or being next to the men or alone.

Moazami: Many of the technological advances in the field of photography coincided with the westward expansion of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was also a period of transition for Native people, who were forced from their traditional homelands and made to live on reservations.

All of a sudden, you had these anthropologists and missionaries and government employees, and even teachers, and they were all grabbing these easy-to-use, handheld cameras with dry plate negatives and, later, film negatives to document their time working with Native communities. Many times, they might have documented it to show their success, for example, at assimilating Native peoples. Though Fred E. Miller, I do believe, was just documenting his life and the people around him. Miller was trained as a photographer; however, he was working with the Crow in the capacity of a government employee rather than that of a commercial photographer. Throssel did some work as a photographer for the Office of Indian Affairs.

Red Star: Yes, Miller and Throssel, who both worked for Indian Services on the Crow reservation, also took personal photographs of regular life on the reservation, gaining the trust of the community to photograph some of their intimate events.

Moazami: Consequently, these photographs give you a glimpse of what everyday life might have been like for various Native communities. You get photographs that document not only chiefs and leaders in the community but also women and men and children, the people who didn’t have the opportunity to go to photography studios.

With studio portraiture, people would always dress up in their best outfits, and they would be posed. Often a photographer would give Native individuals props to make them look like a stereotypical Indian, an archetype. With amateur and candid photographs, you’ve got people wearing their everyday clothing, going about their daily chores, making food for their families. Many amateur photographs were not widely published or circulated; they’re incredibly rare, whereas with Edward Curtis, his photographs are represented in every repository.

Red Star: Curtis also photographed my community, but I love the Throssel and Miller images more. Maybe because the community really trusted them. Throssel’s portraits of women are extraordinary, so powerful and dignified, really at the forefront of his imagery, whereas I feel like Curtis mainly focused on chiefs and warriors and scouts and things like that. In the Miller and Throssel photographs, it was nice to see some of the camp images of women beading or cooking, or being next to the men or alone.

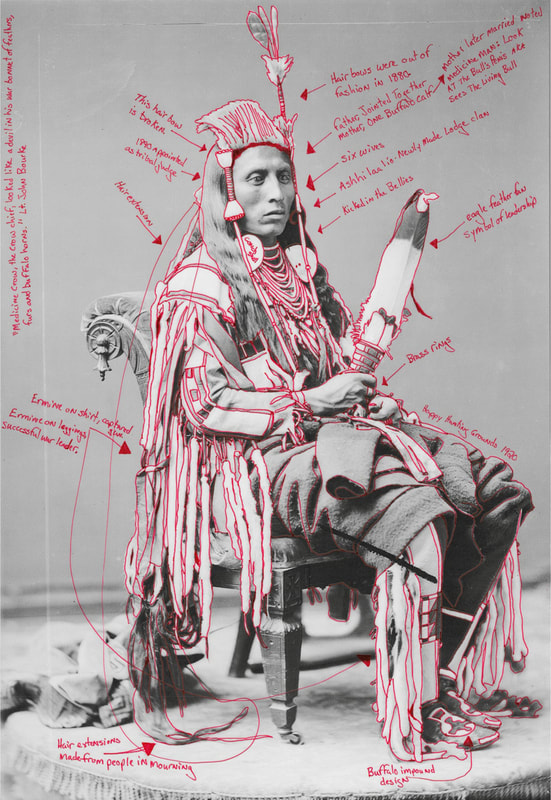

Red Star: One of the things that I love in historical images is minutiae like rings or unintentional background details like dogs or chickens. Tracing a small detail can lead to finding out about a trade system with certain shells, for instance. What are some of the things researchers tend to pay attention to?

Moazami: I am always looking for the who, what, where, when, and why of a photograph. The first way I do that is by seeing photographs as objects themselves. A lot of people think of photographs as two-dimensional, but they’re really three-dimensional. You can answer a lot of questions by just examining the physical photograph itself. You need to learn how to read a photograph and employ some visual literacy when you’re working with photographs.

For example, if you have a cabinet card or a stereograph, it’s a physical thing. You can hold it. You can turn it over. And it gives you a sense of the photograph’s purpose, as to why it was made—for entertainment, to send to loved ones. Also, if you look at the photograph, you might be able to figure out its photographic process or what the date was. If you have a nitrate negative, you can narrow down when it was shot. Technology details, cars, or telephone poles can help you figure out when the photograph might have been taken. You can zoom in and see details, such as the date on a license plate.

Moazami: I am always looking for the who, what, where, when, and why of a photograph. The first way I do that is by seeing photographs as objects themselves. A lot of people think of photographs as two-dimensional, but they’re really three-dimensional. You can answer a lot of questions by just examining the physical photograph itself. You need to learn how to read a photograph and employ some visual literacy when you’re working with photographs.

For example, if you have a cabinet card or a stereograph, it’s a physical thing. You can hold it. You can turn it over. And it gives you a sense of the photograph’s purpose, as to why it was made—for entertainment, to send to loved ones. Also, if you look at the photograph, you might be able to figure out its photographic process or what the date was. If you have a nitrate negative, you can narrow down when it was shot. Technology details, cars, or telephone poles can help you figure out when the photograph might have been taken. You can zoom in and see details, such as the date on a license plate.

Charles Milton Bell, Studio portrait of Apsáalooke (Crow) delegation, 1880. Front row, left to right: King Crow; Medicine Crow; Long Elk; Chief Yshidiapas or Aleck- Shea-Ahoos, called Plenty Coups (Many Valorous Achievements in Battle with the Coup Stick); Pretty Eagle. Back row, left to right: Addison M. Quivey (interpreter); Two Belly; Augustus R. Keller (agent); Thomas Stewart (interpreter). Apsáalooke men wear traditional clothing, including fringed and beaded hide shirts and beaded necklaces, and some hold tomahawks and fans. Interpreters and agent wear suits. Courtesy the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Red Star: What sort of responsibilities, besides the care of these archives, should institutions have to the contemporary communities these historical records are tied to? What are some ways you see institutions building connections with Native communities?

Moazami: We definitely have a responsibility to Native communities, and we need to take Native voices into consideration when we’re working with their historical records. For example, at NMAI, we respect the wishes of communities in regard to photographs or materials that are deemed culturally sensitive. We would never place culturally sensitive materials online, and if somebody contacts us and wants to publish a sensitive image, we tell them they need to get permission from the tribe.

We have paid internships for Native students who are interested in becoming museum or archival professionals. We’ve had projects where interns have incorporated their Indigenous language into finding aids and catalog records.

At the museum, we see ourselves as stewards of the collection. We’re not owners. And we see ourselves as caring for the collections for future generations. We have a Community Loans Program, where we work in partnership with source communities to send materials back to tribal cultural centers for long-term loans. Recently, one hundred Tewa Pueblo vessels were returned home for display at Poeh Cultural Center in Pojoaque, New Mexico. It was the result of several years of collaboration between the Tewa communities and NMAI. We also practice traditional care, where we incorporate the source community’s wishes for how objects should be cared for, such as if it should be oriented facing a certain cardinal direction. We give opportunities for people to leave offerings. We also have indoor and outdoor ceremonial spaces, where visiting community members can actually use objects to perform a ceremony or blessing on-site—a lot of museums don’t even let you touch objects.

Red Star: The history of NMAI hasn’t always been one of stewardship. When did that switch happen, from the old colonial standard to the stewardship approach?

Moazami: It’s an interesting question. I believe the museum really started to incorporate Native perspectives and voices into its exhibitions, catalog records, and public programming in the 1970s. I work with a lot of photographs that document the museum’s activities, and I find photographs from that time period documenting curators working directly with Native communities at the museum.

Red Star: One of the most fun parts of finding images and objects from my community is that I have wonderful phone calls with my father. I’ll ask him all sorts of questions based on things I saw in the archives or names that popped up. But always in these conversations my dad will end up saying, “Ah, I wish your grandmother or grandpa was still here, because they’d be able to identify these people.” For me that just adds urgency to the conversations, even to talking to my dad about the knowledge he holds. I want to make sure to have these conversations with him, to try to get as much information from him as possible.

Moazami: In the past, museums have always acted as an authority, and it’s reflected in our catalog records. What’s changed is that museum professionals admit that we’re not the experts. People from the source communities are the experts, and the people whose ancestors are depicted in the photographs are the experts.

Even when you and I were working together, I could help you identify photographic processes, but you were telling me in great detail about all the activities depicted in the photographs. You provided so much personal insight. That is a big change—this collaborative effort, this dialogue between museum professionals and Native community members.

Moazami: We definitely have a responsibility to Native communities, and we need to take Native voices into consideration when we’re working with their historical records. For example, at NMAI, we respect the wishes of communities in regard to photographs or materials that are deemed culturally sensitive. We would never place culturally sensitive materials online, and if somebody contacts us and wants to publish a sensitive image, we tell them they need to get permission from the tribe.

We have paid internships for Native students who are interested in becoming museum or archival professionals. We’ve had projects where interns have incorporated their Indigenous language into finding aids and catalog records.

At the museum, we see ourselves as stewards of the collection. We’re not owners. And we see ourselves as caring for the collections for future generations. We have a Community Loans Program, where we work in partnership with source communities to send materials back to tribal cultural centers for long-term loans. Recently, one hundred Tewa Pueblo vessels were returned home for display at Poeh Cultural Center in Pojoaque, New Mexico. It was the result of several years of collaboration between the Tewa communities and NMAI. We also practice traditional care, where we incorporate the source community’s wishes for how objects should be cared for, such as if it should be oriented facing a certain cardinal direction. We give opportunities for people to leave offerings. We also have indoor and outdoor ceremonial spaces, where visiting community members can actually use objects to perform a ceremony or blessing on-site—a lot of museums don’t even let you touch objects.

Red Star: The history of NMAI hasn’t always been one of stewardship. When did that switch happen, from the old colonial standard to the stewardship approach?

Moazami: It’s an interesting question. I believe the museum really started to incorporate Native perspectives and voices into its exhibitions, catalog records, and public programming in the 1970s. I work with a lot of photographs that document the museum’s activities, and I find photographs from that time period documenting curators working directly with Native communities at the museum.

Red Star: One of the most fun parts of finding images and objects from my community is that I have wonderful phone calls with my father. I’ll ask him all sorts of questions based on things I saw in the archives or names that popped up. But always in these conversations my dad will end up saying, “Ah, I wish your grandmother or grandpa was still here, because they’d be able to identify these people.” For me that just adds urgency to the conversations, even to talking to my dad about the knowledge he holds. I want to make sure to have these conversations with him, to try to get as much information from him as possible.

Moazami: In the past, museums have always acted as an authority, and it’s reflected in our catalog records. What’s changed is that museum professionals admit that we’re not the experts. People from the source communities are the experts, and the people whose ancestors are depicted in the photographs are the experts.

Even when you and I were working together, I could help you identify photographic processes, but you were telling me in great detail about all the activities depicted in the photographs. You provided so much personal insight. That is a big change—this collaborative effort, this dialogue between museum professionals and Native community members.

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America.”

|

|

Delve deeper |