This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the PhotographerKija Lucas is an artist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She uses photography to explore ideas of home, heritage, and inheritance. She is interested in how ideas are passed down and seemingly inconsequential moments create changes that last generations. Lucas received her BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and her MFA from Mills College. She has been an Artist in Residence at Montalvo Center for the Arts, Grin City Collective, and The Wassaic Artist Residency. Her photography is featured in Actual Size!, an exhibition at the International Center of Photography, showing January 28 – May 02, 2022. |

|

Truth in Photography: Can you talk a little bit about your work that is being exhibited at the International Center of Photography?

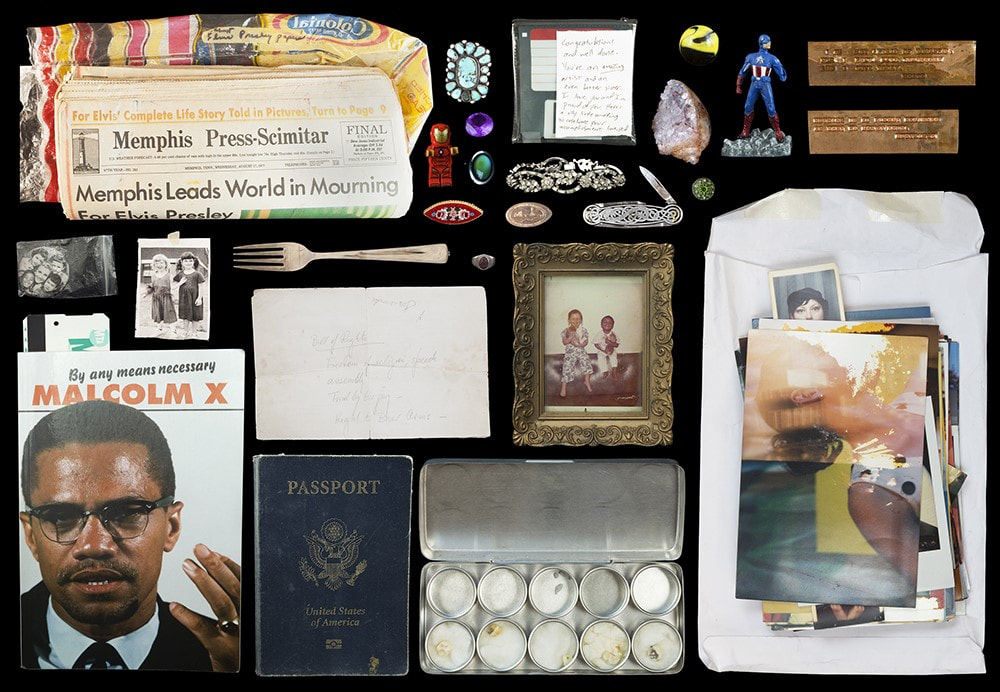

Kija Lucas: The piece that I'm exhibiting at the ICP is from an ongoing body of work called The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy. It has also been called Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment. I've been photographing other people's sentimental objects since 2014, and all of the work is photographed in different places: community centers, art galleries, libraries. Once, I did three months at a bar photographing objects, and I've gone to as many places as I can in the U.S. so far. Then, the objects are put together in Photoshop and printed out onto one image. Lastly, the final work is put into either a frame or vitrine. The piece that I have at the ICP is several objects from different participants that are put together in a vitrine.

Whenever the work is exhibited, I show it as you would see objects in a museum. I don't measure it when I photograph it. So, a lot of the time, the process is me trying to figure out, “what size is this supposed to be when I print it?” The difference for this show is that everything is printed at the exact same size, so I had to make sure that I was spot on with everything.

Kija Lucas: The piece that I'm exhibiting at the ICP is from an ongoing body of work called The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy. It has also been called Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment. I've been photographing other people's sentimental objects since 2014, and all of the work is photographed in different places: community centers, art galleries, libraries. Once, I did three months at a bar photographing objects, and I've gone to as many places as I can in the U.S. so far. Then, the objects are put together in Photoshop and printed out onto one image. Lastly, the final work is put into either a frame or vitrine. The piece that I have at the ICP is several objects from different participants that are put together in a vitrine.

Whenever the work is exhibited, I show it as you would see objects in a museum. I don't measure it when I photograph it. So, a lot of the time, the process is me trying to figure out, “what size is this supposed to be when I print it?” The difference for this show is that everything is printed at the exact same size, so I had to make sure that I was spot on with everything.

TiP: I think it's really interesting the way in which you personalize objects. That by photographing the object, you're saying something about the person.

Lucas: When I photograph an object, I'm there with the person who owns the object, I'm talking to them about it. And I either write down or have them write down the information about each object, so that I know what makes it sentimental. It's not exactly how a museum would do intake - it's just basic information; the first name of the participant, their age, and the city that they live in at the time of photographing. They are also prompted to give information on the object. Some people give me two pages, some people give me a couple of sentences. Some people have a whole cart full of objects, some people have one thing that they spend a lot of time choosing. It really depends on the participant, but I really think of each of these objects as a stand-in for the person. This is representing you today, and it might not be the thing you choose next year or in a few months, but today this is the thing that you're choosing to represent you.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how museums decide the story, the histories that we hold on to, the objects that we hold on to, what is important. And in my body of work everybody has a story, and everybody has something that they hold on to that can be a part of this.

TiP: Could you talk a little bit about your process? How do you make these photographs?

Lucas: This series begins with a call to a space, or a call from a space, where we decide when and where the images will be made. Then I use social media, my own networks, and ask the space where I'm photographing to do the same. Sometimes I bring fliers with me to try to get people to participate, and then I'll set up a simple backdrop with two lights and my digital camera. Participants will come in and bring their objects, and I'll put the object in front of the backdrop and photograph it. I usually photograph things pretty straightforward, either straight on from the front or from above, and I'll make a few exposures. While I'm doing that, I'm talking to the person who brought the object in. Then I'll have them write down the information on the object or I will write it down. That final image ends up both on the website of Sentimental Taxonomy, but also in wherever the next exhibit is. Lately, when I've exhibited the full body of work, I've also set up an intake center where it will have a backdrop and two lights and my camera, and I'll have hours where I work in the space and photograph objects to include in the next iteration of the exhibit.

TiP: How do objects communicate their meaning?

Lucas: I'm not sure if I can tell you the answer to that, but I do believe that the things that we spend the most time with, maybe they hold the DNA of the participant, because they've been holding on to it for so long or they've worn off a piece of it, or they’ve got their fingerprints all over it, et cetera. It might just remind that one person of an event or a time, but when you put all of the objects together, something that I've noticed that visitors who come to see the work will say is, “Oh, I have one of those. Oh, my grandmother used to make that kind of thing,” and it will remind them of their own experiences. I find that to be a really interesting thing. At first, I thought I'd get certain kinds of things from different age groups or different people, but people really connect with the things that they see that other people have brought in as well.

TiP: How does the process of making the photograph fix the object? Because each photograph is distinct and different.

Lucas: I would say that there's something really interesting about photography, where even though it's just the one object, it's that object at that moment in time, right? So, it could be accidentally lost or destroyed afterwards. It could go and sit in a place in a box somewhere where it's not necessarily seen. But with this work, with photographing it, the only thing you could do with a photograph as far as I'm concerned is either look at it or not look at it. It's there specifically to be seen. With the way that I photograph the objects, often people believe that they’re three dimensional when they look at it, they want to touch the paper. I think that's also an interesting thing. They maintain their object-ness a bit in the photographs. I actually find photography a really interesting place to lie because everybody thinks of it as the truth when they see it. It makes us think about, although this is a photograph, this is not an actual three-dimensional thing. This isn't the thing in front of us. It's an image of the thing.

Lucas: When I photograph an object, I'm there with the person who owns the object, I'm talking to them about it. And I either write down or have them write down the information about each object, so that I know what makes it sentimental. It's not exactly how a museum would do intake - it's just basic information; the first name of the participant, their age, and the city that they live in at the time of photographing. They are also prompted to give information on the object. Some people give me two pages, some people give me a couple of sentences. Some people have a whole cart full of objects, some people have one thing that they spend a lot of time choosing. It really depends on the participant, but I really think of each of these objects as a stand-in for the person. This is representing you today, and it might not be the thing you choose next year or in a few months, but today this is the thing that you're choosing to represent you.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how museums decide the story, the histories that we hold on to, the objects that we hold on to, what is important. And in my body of work everybody has a story, and everybody has something that they hold on to that can be a part of this.

TiP: Could you talk a little bit about your process? How do you make these photographs?

Lucas: This series begins with a call to a space, or a call from a space, where we decide when and where the images will be made. Then I use social media, my own networks, and ask the space where I'm photographing to do the same. Sometimes I bring fliers with me to try to get people to participate, and then I'll set up a simple backdrop with two lights and my digital camera. Participants will come in and bring their objects, and I'll put the object in front of the backdrop and photograph it. I usually photograph things pretty straightforward, either straight on from the front or from above, and I'll make a few exposures. While I'm doing that, I'm talking to the person who brought the object in. Then I'll have them write down the information on the object or I will write it down. That final image ends up both on the website of Sentimental Taxonomy, but also in wherever the next exhibit is. Lately, when I've exhibited the full body of work, I've also set up an intake center where it will have a backdrop and two lights and my camera, and I'll have hours where I work in the space and photograph objects to include in the next iteration of the exhibit.

TiP: How do objects communicate their meaning?

Lucas: I'm not sure if I can tell you the answer to that, but I do believe that the things that we spend the most time with, maybe they hold the DNA of the participant, because they've been holding on to it for so long or they've worn off a piece of it, or they’ve got their fingerprints all over it, et cetera. It might just remind that one person of an event or a time, but when you put all of the objects together, something that I've noticed that visitors who come to see the work will say is, “Oh, I have one of those. Oh, my grandmother used to make that kind of thing,” and it will remind them of their own experiences. I find that to be a really interesting thing. At first, I thought I'd get certain kinds of things from different age groups or different people, but people really connect with the things that they see that other people have brought in as well.

TiP: How does the process of making the photograph fix the object? Because each photograph is distinct and different.

Lucas: I would say that there's something really interesting about photography, where even though it's just the one object, it's that object at that moment in time, right? So, it could be accidentally lost or destroyed afterwards. It could go and sit in a place in a box somewhere where it's not necessarily seen. But with this work, with photographing it, the only thing you could do with a photograph as far as I'm concerned is either look at it or not look at it. It's there specifically to be seen. With the way that I photograph the objects, often people believe that they’re three dimensional when they look at it, they want to touch the paper. I think that's also an interesting thing. They maintain their object-ness a bit in the photographs. I actually find photography a really interesting place to lie because everybody thinks of it as the truth when they see it. It makes us think about, although this is a photograph, this is not an actual three-dimensional thing. This isn't the thing in front of us. It's an image of the thing.

TiP: Could you finish the sentence, truth in photography is…

Lucas: Truth in photography is not necessarily the truth. It's a moment in time. It's a great place to lie, because a photograph is thought of as the truth. It's maybe a version of the truth, but it's not necessarily the whole truth. I'm not sure that we can actually find the whole truth in anything.

TiP: It seems to me in your work that you present the object, and the object speaks for itself, through the way it appears.

Lucas: I feel like it does in a way. Then again, it is the object that a person chose to bring in to have me photograph, and then it is the way that I chose to photograph the object at the same time. So as much as I would like to use the visual tropes of being objective, I have this plain background presenting this thing as it is, but it's actually the way that I see it. That is in the image, right? I think it's really interesting thinking about the idea of the mechanical eye, and I try to imitate that idea as much as possible, but I have to admit that I’m the author. The photographer is in there making a decision about what angle to photograph it at, and how to light it. All of those types of things affect the way that we see that image.

TiP: How does lighting affect your work?

Lucas: I think lighting is important because it can change the way you see something. You turn an object slightly and have the light hit it a little bit differently. You change the distance of the light from the object a bit, and it changes the way that you see something. It can really highlight a certain area. It can make it so something's more visible to you or to the viewer. When you're having a meal outside at magic hour, and the sun hits the face of the person sitting across from you just right, you want to photograph them, because it's the most beautiful thing. That person looked the same before, but the way the light is hitting them, it changes it. And I try to light an object to evoke that beauty. I know we're not supposed to use that word, but I think it's important. I try to make things as beautiful as possible when I photograph them.

TiP: I think it's interesting that the word beauty, like the word truth, photographers and artists in the contemporary world want to avoid.

Lucas: Oh yeah. I ran right towards those things. I'm like, “oh nostalgia, you’re not to talk about that. Let me run right into it.”

TiP: Why do you think contemporary artists avoid talking about truth and beauty?

Lucas: I’m not sure that I have the answer to that, but I do know that it's something that I was discouraged from doing. From talking about beauty, or… I don't know about truth, but definitely nostalgia or sentiment, which is exactly why I named the body of work Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, because I wanted to challenge the idea that we're not supposed to be sentimental as artists, that we're supposed to be objective and intellectual about everything. I wanted to challenge that because I think that those things are also valid and important.

Lucas: Truth in photography is not necessarily the truth. It's a moment in time. It's a great place to lie, because a photograph is thought of as the truth. It's maybe a version of the truth, but it's not necessarily the whole truth. I'm not sure that we can actually find the whole truth in anything.

TiP: It seems to me in your work that you present the object, and the object speaks for itself, through the way it appears.

Lucas: I feel like it does in a way. Then again, it is the object that a person chose to bring in to have me photograph, and then it is the way that I chose to photograph the object at the same time. So as much as I would like to use the visual tropes of being objective, I have this plain background presenting this thing as it is, but it's actually the way that I see it. That is in the image, right? I think it's really interesting thinking about the idea of the mechanical eye, and I try to imitate that idea as much as possible, but I have to admit that I’m the author. The photographer is in there making a decision about what angle to photograph it at, and how to light it. All of those types of things affect the way that we see that image.

TiP: How does lighting affect your work?

Lucas: I think lighting is important because it can change the way you see something. You turn an object slightly and have the light hit it a little bit differently. You change the distance of the light from the object a bit, and it changes the way that you see something. It can really highlight a certain area. It can make it so something's more visible to you or to the viewer. When you're having a meal outside at magic hour, and the sun hits the face of the person sitting across from you just right, you want to photograph them, because it's the most beautiful thing. That person looked the same before, but the way the light is hitting them, it changes it. And I try to light an object to evoke that beauty. I know we're not supposed to use that word, but I think it's important. I try to make things as beautiful as possible when I photograph them.

TiP: I think it's interesting that the word beauty, like the word truth, photographers and artists in the contemporary world want to avoid.

Lucas: Oh yeah. I ran right towards those things. I'm like, “oh nostalgia, you’re not to talk about that. Let me run right into it.”

TiP: Why do you think contemporary artists avoid talking about truth and beauty?

Lucas: I’m not sure that I have the answer to that, but I do know that it's something that I was discouraged from doing. From talking about beauty, or… I don't know about truth, but definitely nostalgia or sentiment, which is exactly why I named the body of work Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, because I wanted to challenge the idea that we're not supposed to be sentimental as artists, that we're supposed to be objective and intellectual about everything. I wanted to challenge that because I think that those things are also valid and important.

TiP: Jorge Luis Borges talked about the idea that we remember our lives in terms of quotations. And those quotations define who we are.

Lucas: I think the photograph even could be thought about in that idea of quotations, because if you look at a photograph from your childhood, does your memory come from your feelings of nostalgia or sentiment? Or do they come from the thing that you saw in the image, your actual memory, the stories that you are told about that time, or the stories that you've told repeatedly about that time? Those sorts of snippets are the things that we tend to remember, especially since photography is so abundant now. Everyone has a camera in their pocket and is constantly recording stuff. Is it the memory, or is it the thing that you can see in the recording of that time?

TiP: That’s an excellent point.

Lucas: I'm really interested in those moments of time, not only through my own experience, but how does the experience of my seventh-generation great-grandmother affect who I am today? That is both through epigenetics and DNA, but it's also through sociological experience and the way that the world has been and how those things get passed down through time, which I think are also intertwined.

When I first started photographing pillows, I was really thinking about how our physical DNA gets entwined in an object that we spend time on. So that pillow, eventually, has got a bunch of our skin inside of it, our drool on it, et cetera, and it's covered by this piece of cloth so that you don't see any of it. You don't see it when you put your head on the pillow. When someone else comes in the room, they don't see that. Stripping the pillow of its cover and really seeing what's inside and seeing the way that our physical body has changed this object, and how our body is also a part of the object at the same time. Thinking about it in the same way that I would think about a portrait– I stopped photographing people for my work– the last one I took was in 2008, grad school. I had this ethical dilemma of how to represent another person in a photograph and whether I was doing justice by them, and I think a lot of photographers think about that, but not all of them do. But for me, I couldn't figure that out. But my work is 100% about people and our relationships with one another and our relationships with the space that we spent time in and the objects that were around and how we affect one another. Figuring out how to represent a person with an object, something like a pillow, made sense to me, and it changed and evolved from there.

TiP: It's interesting to me when you see objects in actual size, you confront them in a different way. Talk a little bit about how we interrogate the object by what we see.

Lucas: I think that a lot of times with an object, we’re projecting our own experience onto it. In the photograph of an object, or seeing an object somewhere, both those things, a person that holds on to an object, perhaps when they see it, it reminds them of a person or a place or a time in their life. Perhaps it reminds them of a burden that they carry as well. So, when they see that object, they're going to see one thing. But when someone else sees the photograph of that object, they're going to see their own experience with a thing that is similar to that object.

TiP: I think that's really interesting because when we see an object that we're familiar with in a photograph, then we connect to it in a different way.

Lucas: Definitely. Sometimes also a person will see an object in the photograph, surrounded by all of these sentimental objects, and think, how is that sentimental? They'll be like, why would somebody hold on to that? But the thing is, not everybody needs to know the answer to that question, but that's part of what I'm doing as well with collecting the information. There's another image that is not in the exhibition, there’s a picture of the carcass of an English starling. People will see that and they'll think, why on earth would somebody carry this with them? But the person who carries it with them, he's an artist and an ecologist, and it makes him think about the beach that he grew up going to as a child. That's where he found that piece and he knows how to take care of this thing. He puts it in the freezer, has it in every studio where he's lived for the last 20 years, moved it across country with him. But other people don't have that same experience with this object, so they're going to think something completely different about it, you know? I think it's really important to put them in context with one another as well.

When we see all of these things together, like when you go to a museum and you see the antiquities department, or something like that, and all of these things that have been collected and stolen from places, they're all put into one place together and the curator decides what the context is for those things, it tells a different story than seeing one of them at a time. The same thing with the objects in this piece and in the show. We can understand that these all have a similar reason why somebody might hold on to the thing, even though that's not the thing that you would hold onto.

TiP: I think that photographing these objects dignifies them in a certain way. It makes them special. It makes you as a viewer, whether or not you understand the context, question them and maybe appreciate them in a way that you didn't think you might otherwise.

Lucas: I agree there's something that makes them work. There's something about photographing a thing that makes it feel worthy of remembering. There's a reason why somebody photographed this object, there's a reason why somebody photographed this scene, and whether or not it is worthy of remembering, it's this thing that the person who had the camera chose to photograph, or it's the thing that the person participating in this project chose to bring in to be photographed. It's almost creating something new. Here's a thing that has to be looked at and revered.

Lucas: I think the photograph even could be thought about in that idea of quotations, because if you look at a photograph from your childhood, does your memory come from your feelings of nostalgia or sentiment? Or do they come from the thing that you saw in the image, your actual memory, the stories that you are told about that time, or the stories that you've told repeatedly about that time? Those sorts of snippets are the things that we tend to remember, especially since photography is so abundant now. Everyone has a camera in their pocket and is constantly recording stuff. Is it the memory, or is it the thing that you can see in the recording of that time?

TiP: That’s an excellent point.

Lucas: I'm really interested in those moments of time, not only through my own experience, but how does the experience of my seventh-generation great-grandmother affect who I am today? That is both through epigenetics and DNA, but it's also through sociological experience and the way that the world has been and how those things get passed down through time, which I think are also intertwined.

When I first started photographing pillows, I was really thinking about how our physical DNA gets entwined in an object that we spend time on. So that pillow, eventually, has got a bunch of our skin inside of it, our drool on it, et cetera, and it's covered by this piece of cloth so that you don't see any of it. You don't see it when you put your head on the pillow. When someone else comes in the room, they don't see that. Stripping the pillow of its cover and really seeing what's inside and seeing the way that our physical body has changed this object, and how our body is also a part of the object at the same time. Thinking about it in the same way that I would think about a portrait– I stopped photographing people for my work– the last one I took was in 2008, grad school. I had this ethical dilemma of how to represent another person in a photograph and whether I was doing justice by them, and I think a lot of photographers think about that, but not all of them do. But for me, I couldn't figure that out. But my work is 100% about people and our relationships with one another and our relationships with the space that we spent time in and the objects that were around and how we affect one another. Figuring out how to represent a person with an object, something like a pillow, made sense to me, and it changed and evolved from there.

TiP: It's interesting to me when you see objects in actual size, you confront them in a different way. Talk a little bit about how we interrogate the object by what we see.

Lucas: I think that a lot of times with an object, we’re projecting our own experience onto it. In the photograph of an object, or seeing an object somewhere, both those things, a person that holds on to an object, perhaps when they see it, it reminds them of a person or a place or a time in their life. Perhaps it reminds them of a burden that they carry as well. So, when they see that object, they're going to see one thing. But when someone else sees the photograph of that object, they're going to see their own experience with a thing that is similar to that object.

TiP: I think that's really interesting because when we see an object that we're familiar with in a photograph, then we connect to it in a different way.

Lucas: Definitely. Sometimes also a person will see an object in the photograph, surrounded by all of these sentimental objects, and think, how is that sentimental? They'll be like, why would somebody hold on to that? But the thing is, not everybody needs to know the answer to that question, but that's part of what I'm doing as well with collecting the information. There's another image that is not in the exhibition, there’s a picture of the carcass of an English starling. People will see that and they'll think, why on earth would somebody carry this with them? But the person who carries it with them, he's an artist and an ecologist, and it makes him think about the beach that he grew up going to as a child. That's where he found that piece and he knows how to take care of this thing. He puts it in the freezer, has it in every studio where he's lived for the last 20 years, moved it across country with him. But other people don't have that same experience with this object, so they're going to think something completely different about it, you know? I think it's really important to put them in context with one another as well.

When we see all of these things together, like when you go to a museum and you see the antiquities department, or something like that, and all of these things that have been collected and stolen from places, they're all put into one place together and the curator decides what the context is for those things, it tells a different story than seeing one of them at a time. The same thing with the objects in this piece and in the show. We can understand that these all have a similar reason why somebody might hold on to the thing, even though that's not the thing that you would hold onto.

TiP: I think that photographing these objects dignifies them in a certain way. It makes them special. It makes you as a viewer, whether or not you understand the context, question them and maybe appreciate them in a way that you didn't think you might otherwise.

Lucas: I agree there's something that makes them work. There's something about photographing a thing that makes it feel worthy of remembering. There's a reason why somebody photographed this object, there's a reason why somebody photographed this scene, and whether or not it is worthy of remembering, it's this thing that the person who had the camera chose to photograph, or it's the thing that the person participating in this project chose to bring in to be photographed. It's almost creating something new. Here's a thing that has to be looked at and revered.

|

|

|