This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About Brian WallisBrian Wallis is Executive Director of the Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW), now located in Kingston, NY. He was Deputy Director and Chief Curator at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York from 2000 to 2015. Under his leadership, ICP presented more than 150 exhibitions and installations, including Only Skin Deep: Visions of the American Self; African American Vernacular Photography; Strangers: The First ICP Triennial of Photography and Video; and Weegee: Murder Is My Business. Before joining ICP, Wallis worked at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art. More recently, Wallis worked as curator for The Walther Collection, a museum of photography with facilities in New York and Neu Ulm, Germany, where he oversaw numerous exhibitions, including Imagining Everyday Life: Encounters with Vernacular Photography, awarded the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation prize for Photography Catalogue of the Year in 2020. |

|

Race, Love, and Labor

(an excerpt)

It is impossible to separate the history of photography from the history of labor, love, and race in America. At the advent of photography, a deal was struck: the medium would document both the intimacies we cherish and their cost in human toil. It is a paradox that Frederick Douglass would remind us of during the Civil War: photographs were instruments used to erase part of the human family and it would take images of human dignity and determination to rectify it. The labor of photography is to wrestle with this legacy. It is not work but labor: a means through which we birth ourselves anew.

This exhibition, culled from the collection of the Center for Photography at Woodstock’s Artist-in-Residency program, displays images by artists who understand the needs of labor in the fullest sense of the word. They are part of a twenty-year-old tradition at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, which offers artists of color one of the requirements for a sterling creative practice—embryonic time to probe deeply, unfettered by distractions. In this exhibition, we not only honor this residency but also highlight the themes that have emerged from the resulting, irreplaceable pictures. What unites these images is an animating sense of what it means to live in this lineage of photography’s paradox—to reduce and to exult. These photographs, the gift of a moment in time through a unique residency, show us where a future path may lead.

~Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Curator

This exhibition is a partial reconstruction —an excerpt—of an earlier project organized by Dr. Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, associate professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University and founder of the Vision & Justice Project, and originally shown at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz in 2014.

(an excerpt)

It is impossible to separate the history of photography from the history of labor, love, and race in America. At the advent of photography, a deal was struck: the medium would document both the intimacies we cherish and their cost in human toil. It is a paradox that Frederick Douglass would remind us of during the Civil War: photographs were instruments used to erase part of the human family and it would take images of human dignity and determination to rectify it. The labor of photography is to wrestle with this legacy. It is not work but labor: a means through which we birth ourselves anew.

This exhibition, culled from the collection of the Center for Photography at Woodstock’s Artist-in-Residency program, displays images by artists who understand the needs of labor in the fullest sense of the word. They are part of a twenty-year-old tradition at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, which offers artists of color one of the requirements for a sterling creative practice—embryonic time to probe deeply, unfettered by distractions. In this exhibition, we not only honor this residency but also highlight the themes that have emerged from the resulting, irreplaceable pictures. What unites these images is an animating sense of what it means to live in this lineage of photography’s paradox—to reduce and to exult. These photographs, the gift of a moment in time through a unique residency, show us where a future path may lead.

~Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Curator

This exhibition is a partial reconstruction —an excerpt—of an earlier project organized by Dr. Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, associate professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University and founder of the Vision & Justice Project, and originally shown at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz in 2014.

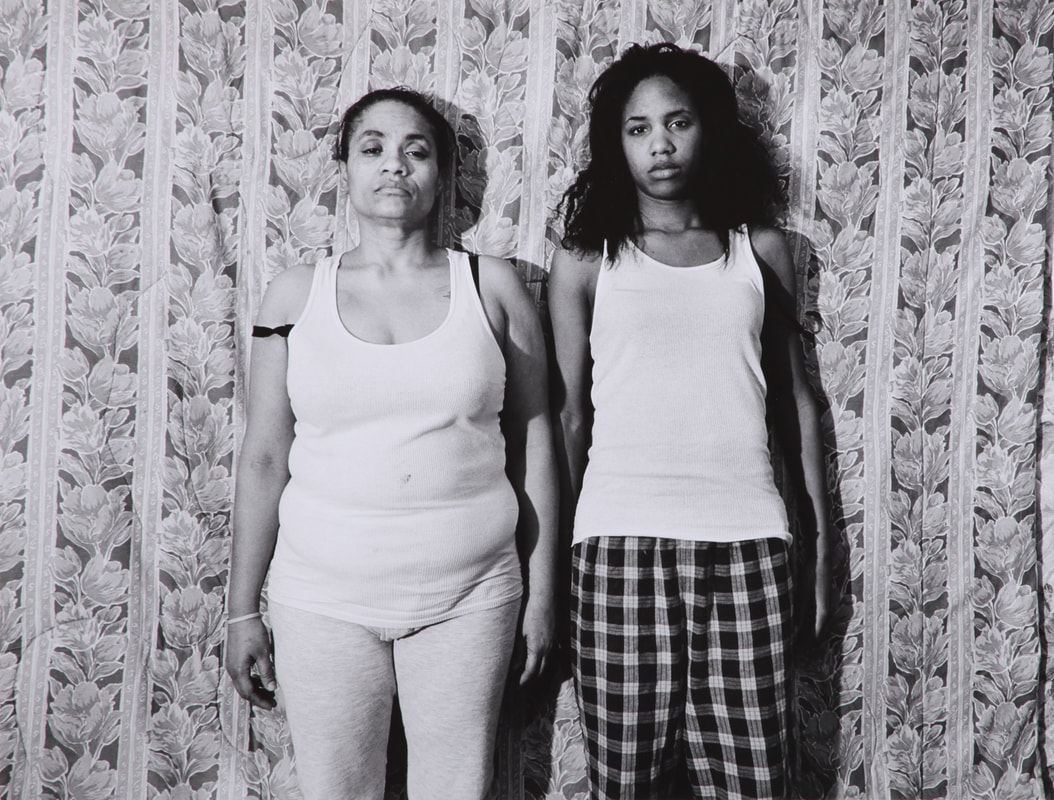

LaToya Ruby Frazier

American, born 1982

Growing up in 1980s Braddock, Pennsylvania, a gritty, steel-producing suburb of Pittsburgh, LaToya Ruby Frazier began photographing her family and neighborhood at the age of sixteen. As Braddock deindustrialized, she and her family were regularly exposed to dangerous chemicals and particulates living in close proximity to the region’s last surviving steel mill. Frazier’s documentary photographs include self-portraits, portraits of her mother and grandmother, and records of their domestic space, interweaving the fate of a Black family with a political allegory about the environmental and physical degradation of their town. She made images not as a dispassionate outsider, but as a vulnerable insider and participant, calling her work “conceptual documentary art.” Printed during her 2008 Woodstock residency, these photographs were published in 2013 as the Aperture monograph “The Notion of Family.”

American, born 1982

Growing up in 1980s Braddock, Pennsylvania, a gritty, steel-producing suburb of Pittsburgh, LaToya Ruby Frazier began photographing her family and neighborhood at the age of sixteen. As Braddock deindustrialized, she and her family were regularly exposed to dangerous chemicals and particulates living in close proximity to the region’s last surviving steel mill. Frazier’s documentary photographs include self-portraits, portraits of her mother and grandmother, and records of their domestic space, interweaving the fate of a Black family with a political allegory about the environmental and physical degradation of their town. She made images not as a dispassionate outsider, but as a vulnerable insider and participant, calling her work “conceptual documentary art.” Printed during her 2008 Woodstock residency, these photographs were published in 2013 as the Aperture monograph “The Notion of Family.”

Truth in Photography: Woostock AIR, the residency program that's been in existence at the Center for Photography at Woodstock for some twenty-five years, seems to be wide reaching. And the works you are showing from that program in “Race, Love, and Labor (an excerpt)” are particularly evocative. As the new director of the Center for Photography at Woodstock, where do you see the institution going?

Brian Wallis: The organization has a long history; it was founded by Howard Greenberg and Michael Feinberg in 1977 as a local, grassroots, artist-run facility for the study and production of photography. In that capacity, it has long been one of the leading small centers for photographers and artists. And it was tied to the very charming artist village of Woodstock. Then, for various reasons, in the midst of the pandemic, the Board moved the center from Woodstock to the nearby city of Kingston, now a thriving cultural hub. And just recently we acquired a massive four-story brick factory building in the old industrial center of Kingston that will be our future home.

What was interesting to me in coming on as the new director of the Center for Photography at Woodstock is the fact that the organization is very community oriented; it’s in our DNA. Now we are in Kingston, in the Midtown Arts District, with a very vital and diverse nexus of artists. We have tried to extend that community by developing partnerships and collaborations with like-minded organizations in and around Kingston. For example, we collaborated with the Woodstock Film Festival on presenting a few documentary films; we partnered. with My Kingston Kids to provide free photography workshops for high school students; and we joined with a group called MADD to co-organize student internships. So, we’ve been working over the past six months to present photography workshops, lectures, and exhibitions to embed the organization more deeply into the cultural activities of our new home. For example, we just started a new program of lectures called “Meet the Artists,” which is a weekly opportunity for local artists and photographers to get up and talk about their work. And that's been extremely successful, both in terms of providing a platform for these artists, but also in allowing the audience members to meet one another and to really fortify the coalition of artists that exists in Kingston.

Brian Wallis: The organization has a long history; it was founded by Howard Greenberg and Michael Feinberg in 1977 as a local, grassroots, artist-run facility for the study and production of photography. In that capacity, it has long been one of the leading small centers for photographers and artists. And it was tied to the very charming artist village of Woodstock. Then, for various reasons, in the midst of the pandemic, the Board moved the center from Woodstock to the nearby city of Kingston, now a thriving cultural hub. And just recently we acquired a massive four-story brick factory building in the old industrial center of Kingston that will be our future home.

What was interesting to me in coming on as the new director of the Center for Photography at Woodstock is the fact that the organization is very community oriented; it’s in our DNA. Now we are in Kingston, in the Midtown Arts District, with a very vital and diverse nexus of artists. We have tried to extend that community by developing partnerships and collaborations with like-minded organizations in and around Kingston. For example, we collaborated with the Woodstock Film Festival on presenting a few documentary films; we partnered. with My Kingston Kids to provide free photography workshops for high school students; and we joined with a group called MADD to co-organize student internships. So, we’ve been working over the past six months to present photography workshops, lectures, and exhibitions to embed the organization more deeply into the cultural activities of our new home. For example, we just started a new program of lectures called “Meet the Artists,” which is a weekly opportunity for local artists and photographers to get up and talk about their work. And that's been extremely successful, both in terms of providing a platform for these artists, but also in allowing the audience members to meet one another and to really fortify the coalition of artists that exists in Kingston.

Endia Beal

American, born 1985

In this short video, Endia Beal presents interviews she conducted with women of color that have careers in various office environments. Beal was struck by the similarities in the women’s stories: they each share personal experiences with ignorance, prejudice, and racism in a corporate workspace. By bringing them together, Beal allows the women to speak with one voice. Since she created this work during her 2013 residency, 9 to 5 has only grown more relevant and timely, especially in the wake of the anti-racism and MeToo movements, which have made visible the prevalence of such workplace harassment.

American, born 1985

In this short video, Endia Beal presents interviews she conducted with women of color that have careers in various office environments. Beal was struck by the similarities in the women’s stories: they each share personal experiences with ignorance, prejudice, and racism in a corporate workspace. By bringing them together, Beal allows the women to speak with one voice. Since she created this work during her 2013 residency, 9 to 5 has only grown more relevant and timely, especially in the wake of the anti-racism and MeToo movements, which have made visible the prevalence of such workplace harassment.

TiP: How does that manifest itself in terms of exhibitions of photography?

Wallis: The exhibitions are another demonstration of that kind of outreach. We've tried to create exhibitions that are diverse in character, with some large scale, art-world oriented exhibitions, such as the extraordinary “Parallel Lives: Photography, Identity, and Belonging,” which curator Maya Benton organized in an abandoned IBM office complex, and which focuses in interesting ways on the psychic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, but also smaller exhibitions that reflect some of the community programs we're doing, such as students exhibiting their work alongside more established artists.

And more recently, what we've tried to do is highlight elements of our collection that either reflect the work of local photographers or touch on topics that we feel would be of interest to our audience. The first exhibition we did in Kingston, for example, was of the work of photographer Doug Menuez, who took documentary portraits of various prominent citizens in Kingston. But we have also shown works from the collection related to Woodstock AIR. This artist in residence program is designed to provide a place for artists and photographers from underserved communities, those not well represented traditionally in conventional art and photography worlds, principally Black, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous, queer, and diasporic artists. We choose ten photographers every year. They stay for a month in the house we have in Woodstock and they create their work. And an interesting stipulation that was created many years ago is that each artist is required to submit work to the permanent collection of the Center for Photography at Woodstock. So as a result, we have an extraordinary collection of work by many photographers, now well known, who came and participated in the residency when they were younger, such as Latoya Ruby Frazier, Danny Tisdale, Deana Lawson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Tommy Kha, and many others.

Wallis: The exhibitions are another demonstration of that kind of outreach. We've tried to create exhibitions that are diverse in character, with some large scale, art-world oriented exhibitions, such as the extraordinary “Parallel Lives: Photography, Identity, and Belonging,” which curator Maya Benton organized in an abandoned IBM office complex, and which focuses in interesting ways on the psychic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, but also smaller exhibitions that reflect some of the community programs we're doing, such as students exhibiting their work alongside more established artists.

And more recently, what we've tried to do is highlight elements of our collection that either reflect the work of local photographers or touch on topics that we feel would be of interest to our audience. The first exhibition we did in Kingston, for example, was of the work of photographer Doug Menuez, who took documentary portraits of various prominent citizens in Kingston. But we have also shown works from the collection related to Woodstock AIR. This artist in residence program is designed to provide a place for artists and photographers from underserved communities, those not well represented traditionally in conventional art and photography worlds, principally Black, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous, queer, and diasporic artists. We choose ten photographers every year. They stay for a month in the house we have in Woodstock and they create their work. And an interesting stipulation that was created many years ago is that each artist is required to submit work to the permanent collection of the Center for Photography at Woodstock. So as a result, we have an extraordinary collection of work by many photographers, now well known, who came and participated in the residency when they were younger, such as Latoya Ruby Frazier, Danny Tisdale, Deana Lawson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Tommy Kha, and many others.

|

Paul Mpagi Sepuya American, born 1982 While Paul Mpagi Sepuya was living in Woodstock during his 2010 artist residency, he maintained regular correspondence with a friend named Matija. Over the course of his stay, Sepuya received snapshots Matija had made of the artist’s vacant home and bedroom in Brooklyn. He printed, reworked, and rephotographed these snapshots and used his residency to focus on photography’s most essential qualities, its reproducibility, and in particular, the way it can be used to examine the connections between people. Exploring aspects of collaborative self-portraiture, “I make photographs about the act of portrait making,” says Sepuya. “It is about meetings, and how the practice of art-making seeks to construct and define relationships.” |

About seven or eight years ago, Harvard art historian Sarah Elizabeth Lewis created a wonderful exhibition from this collection called “Race, Love, and Labor,” which was shown at the nearby Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY Purchase. And Sarah's exhibition was drawn exclusively from the works our Woodstock AIR artists donated to the Center for Photography at Woodstock after they completed their residency—and it was sensational! On January 14th, we opened “Race, Love, and Labor (an excerpt),” which is a smaller version of Sarah's landmark exhibition. I think it gives a really strong, distilled representation of the significance of the artists who had come through Woodstock AIR, and also the ongoing relevance of the social and political themes they addressed in their photography.

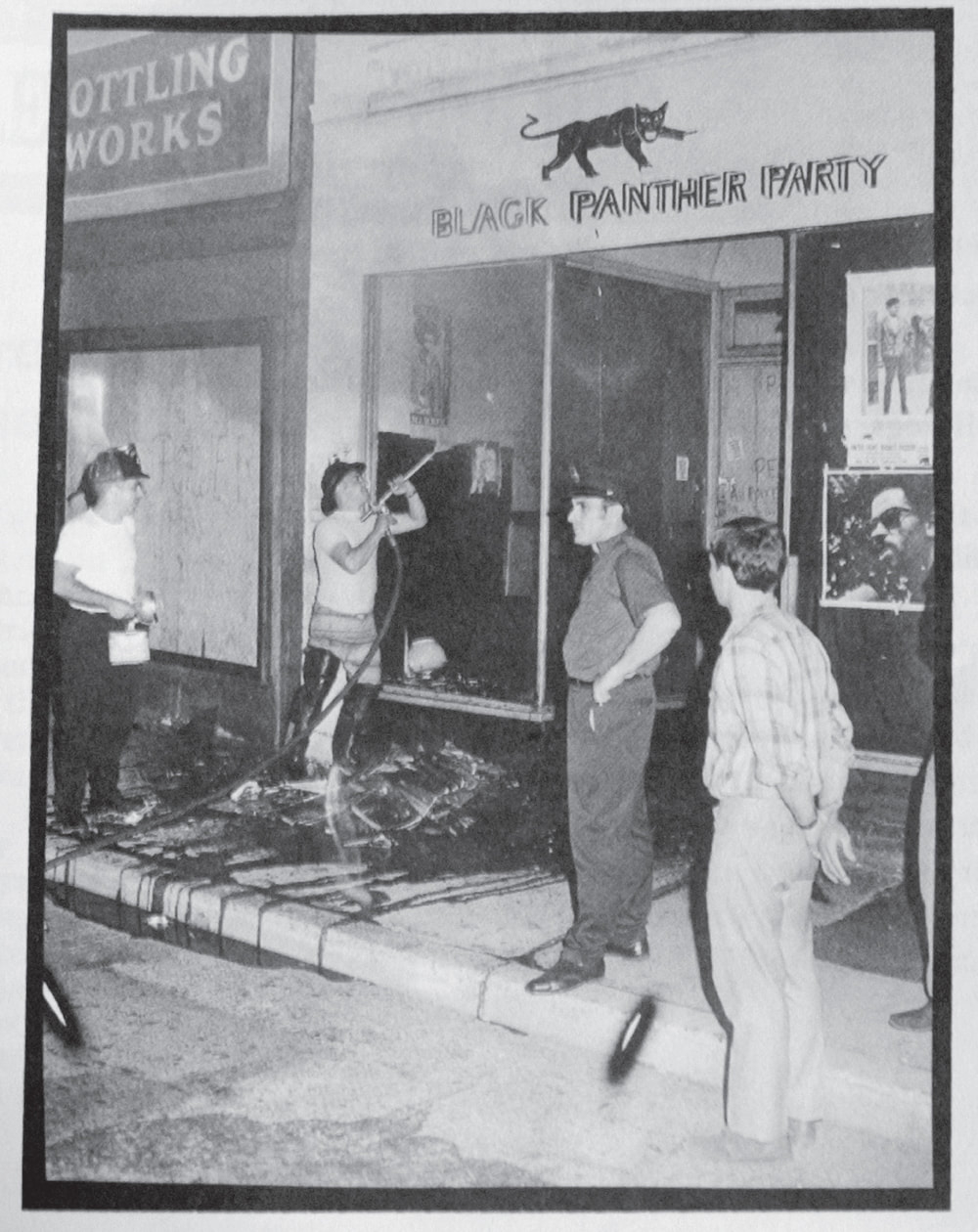

Many of these artists’ projects were directly impacted by their relocation to upstate New York. For example, william cordova’s work “Albany/Peekskill” used Woodstock as a base to research the local impact of the Black Panthers in the Hudson River valley. He photocopied old newspaper files to create a multi-part installation showing how the Panther branch in Peekskill initiated a breakfast program in schools before their headquarters was firebombed by police in 1969. Joanna Tam did a smart series posing in various upstate locales with her hand over her heart to comment on the psychological burden of loyalty oaths immigrants to the U.S. are required to affirm. And LaToya Ruby Frazier, Xaviera Simmons, Tommy Kha, and Deana Lawson all worked on some of their early series in Woodstock many years before recent political activism repositioned the significance of personal and critical issues raised by their work.

Many of these artists’ projects were directly impacted by their relocation to upstate New York. For example, william cordova’s work “Albany/Peekskill” used Woodstock as a base to research the local impact of the Black Panthers in the Hudson River valley. He photocopied old newspaper files to create a multi-part installation showing how the Panther branch in Peekskill initiated a breakfast program in schools before their headquarters was firebombed by police in 1969. Joanna Tam did a smart series posing in various upstate locales with her hand over her heart to comment on the psychological burden of loyalty oaths immigrants to the U.S. are required to affirm. And LaToya Ruby Frazier, Xaviera Simmons, Tommy Kha, and Deana Lawson all worked on some of their early series in Woodstock many years before recent political activism repositioned the significance of personal and critical issues raised by their work.

Tommy Kha

American, born 1988

In Little Polite, West Hurley, NY, Tommy Kha confronts the subject of “yellowface,” the disgraceful practice in Western media, in particular film and theater, where Caucasian actors would use makeup or prosthetics to play East Asian characters, relying on pre-existing stereotypes to guide their flawed interpretation. During his 2011 residency, Kha created a series of self-portraits like the one presented here, using theatrical makeup, props, costumes, and expressions to lampoon the stereotypes long used to dismiss or denigrate people of East Asian descent. This project, called “American Knees,” prefigures Kha’s more recent work, in which he explores the formation of his own racial, sexual, and generational identity as a Chinese-American man.

American, born 1988

In Little Polite, West Hurley, NY, Tommy Kha confronts the subject of “yellowface,” the disgraceful practice in Western media, in particular film and theater, where Caucasian actors would use makeup or prosthetics to play East Asian characters, relying on pre-existing stereotypes to guide their flawed interpretation. During his 2011 residency, Kha created a series of self-portraits like the one presented here, using theatrical makeup, props, costumes, and expressions to lampoon the stereotypes long used to dismiss or denigrate people of East Asian descent. This project, called “American Knees,” prefigures Kha’s more recent work, in which he explores the formation of his own racial, sexual, and generational identity as a Chinese-American man.

TiP: It sounds like Woodstock AIR has had a remarkable impact as a residency program. How has the artist residency evolved? Have the criteria for acceptance changed over the years? Where do you see it going now?

Wallis: Well, I think it's interesting that twenty-five years ago, in the late 1990s, the directors of CPW already recognized that there was a large group of photographers whose work was mostly excluded from conventional galleries, museums, and art writing. In recent years, say within the past five years, there's been a greater attention in the organized cultural sphere to the profound lack (or deliberate exclusion) of non-white, non-urban, non-First World, non-heteronormative voices and visibility. So, the particular focus of the artist residency was clearly designed to redress that imbalance and to provide an important boost for artists and photographers working outside of that system. And, to my mind, it's been successful. Our goal is to expand critical thinking about the social and political uses of photography, and that means we have to embrace and to comprehend divergent ways of thinking about photography. What has always interested me is the critical dialogue that can be sparked by the social event of photography. What I see happening in the Woodstock AIR residency program is a much-expanded conversation that has both energized and intersected with a national cultural conversation about the real meaning of public representations. This has been played out in relation to photographs, but also with regard to physical symbolic monuments, raising questions about individual identity, interpersonal identity, collective identity, social attitudes, and acceptances toward those views.

Wallis: Well, I think it's interesting that twenty-five years ago, in the late 1990s, the directors of CPW already recognized that there was a large group of photographers whose work was mostly excluded from conventional galleries, museums, and art writing. In recent years, say within the past five years, there's been a greater attention in the organized cultural sphere to the profound lack (or deliberate exclusion) of non-white, non-urban, non-First World, non-heteronormative voices and visibility. So, the particular focus of the artist residency was clearly designed to redress that imbalance and to provide an important boost for artists and photographers working outside of that system. And, to my mind, it's been successful. Our goal is to expand critical thinking about the social and political uses of photography, and that means we have to embrace and to comprehend divergent ways of thinking about photography. What has always interested me is the critical dialogue that can be sparked by the social event of photography. What I see happening in the Woodstock AIR residency program is a much-expanded conversation that has both energized and intersected with a national cultural conversation about the real meaning of public representations. This has been played out in relation to photographs, but also with regard to physical symbolic monuments, raising questions about individual identity, interpersonal identity, collective identity, social attitudes, and acceptances toward those views.

|

william cordova American, born Peru, 1969 During the late 1960s, the Black Panthers kept an office in Peekskill, New York, while organizing their Free Breakfast Program and political education classes – until 1969 when police attempted to burn their building down. An activist group called the Brothers protested racist hiring practices throughout the Capital District and published a newspaper called The Albany Liberator from 1967-1972. This surprising and little-known history of Black Power in the region forms the foundation of william cordova’s Albany/Peekskill, an assemblage of archival records found in the University of Albany’s library and elsewhere. In addition, cordova includes two of his own photographs in this multi-part work, created during his 2007 Woodstock residency. They show the locations of the former headquarters of the Panthers and the Brothers, both now long demolished. By highlighting the community service both groups engaged in, and juxtaposing it with the violence they endured as a result, cordova valorizes these activists and brings their past into the present. |

TiP: Everything you're saying speaks to questions and issues about truth, not only in photography, but of photography. From what you're saying about the diversity of makers, that is a more true view of the scope of contemporary photography, but it's also the scope of the history of photography. In your past work you have always stressed photography by and about overlooked subjects, makers, users, and communities.

Wallis: One issue that I’ve consistently engaged with, in addressing photography, has been the notion of truth, a concept that I'm extremely skeptical about. Obviously, truth is subjective: it depends on an individual's perspective, or relationship to an image, or an event. And that would make truth in photography as various as all of the audience members and all of their multifaceted intentions. Truth is always relative. What is accepted as a widely held truth is really just a majority decision. This is clear in the debates in U.S. politics and in the media over last seven or eight years; this could be seen as an ongoing national debate about the nature and value of truth as a shared belief system. The relationship of truth to information on social media, and in political discourse has provided ample demonstration that what we used to call “truth” is now a very fungible and manipulable field. What I've tried to do in looking at photography is really to expand the possibility of available truths. For example, when I worked at the International Center of Photography, a couple of areas that we tried to enlarge were the geographic, material, and class-based structures of our conventionalized understanding of photography. One strategy was to look at the practices of photography and the cultural attitudes towards photography outside of the European/North American corridor, to look at how photography was created and understood and deployed in Africa, Asia, South America, and other areas of the globe. A second approach was to consider the distribution and reception of photography in popular media, and to create a dialogue around the uses of photography in print. Most photographs are not perceived through museums or exhibitions, but through publications. And then a third area of investigation was vernacular photography, the domestic, popular, nonprofessional, and utilitarian applications of photography. These are instances, such as the family album, where photography serves as a means of direct communication or as a seemingly objective record of certain people or events or ideas.

And that's where we circle back to the question of truth. Photography was employed instrumentally to shape international modernist culture throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was a form of imperialistic propaganda, a way to separate, to divide, and to establish domain over peoples, using photography to demean, or oppress, or categorize. And a second consideration would be the widespread assertion of photography as a representation of objective fact, legally, scientifically, and more generally, in the public mind: what you see in photographs is true and demonstrates an irrefutable relationship to facts in the world. Both of these widespread uses of or approaches to photography have clearly had devastating effects, but they also are, in retrospect, demonstrably untrue and deliberately fictional. They reflect not only extreme political and cultural biases but also represent intentional campaigns to deceive and misrepresent through photography. What has interested me, especially in the work of contemporary photography over the last ten or twenty years, has been the conceptual endeavor by many photographers to try to undo the destruction done by these campaigns in the name of truth, to question critically the concepts of authorship, originality, quality, objectivity, and singularity. The gender biases of photography, the cultural biases of photography, the racial biases of photography, and the national biases of photography have created exclusions and invisibilities in information and histories.

Wallis: One issue that I’ve consistently engaged with, in addressing photography, has been the notion of truth, a concept that I'm extremely skeptical about. Obviously, truth is subjective: it depends on an individual's perspective, or relationship to an image, or an event. And that would make truth in photography as various as all of the audience members and all of their multifaceted intentions. Truth is always relative. What is accepted as a widely held truth is really just a majority decision. This is clear in the debates in U.S. politics and in the media over last seven or eight years; this could be seen as an ongoing national debate about the nature and value of truth as a shared belief system. The relationship of truth to information on social media, and in political discourse has provided ample demonstration that what we used to call “truth” is now a very fungible and manipulable field. What I've tried to do in looking at photography is really to expand the possibility of available truths. For example, when I worked at the International Center of Photography, a couple of areas that we tried to enlarge were the geographic, material, and class-based structures of our conventionalized understanding of photography. One strategy was to look at the practices of photography and the cultural attitudes towards photography outside of the European/North American corridor, to look at how photography was created and understood and deployed in Africa, Asia, South America, and other areas of the globe. A second approach was to consider the distribution and reception of photography in popular media, and to create a dialogue around the uses of photography in print. Most photographs are not perceived through museums or exhibitions, but through publications. And then a third area of investigation was vernacular photography, the domestic, popular, nonprofessional, and utilitarian applications of photography. These are instances, such as the family album, where photography serves as a means of direct communication or as a seemingly objective record of certain people or events or ideas.

And that's where we circle back to the question of truth. Photography was employed instrumentally to shape international modernist culture throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was a form of imperialistic propaganda, a way to separate, to divide, and to establish domain over peoples, using photography to demean, or oppress, or categorize. And a second consideration would be the widespread assertion of photography as a representation of objective fact, legally, scientifically, and more generally, in the public mind: what you see in photographs is true and demonstrates an irrefutable relationship to facts in the world. Both of these widespread uses of or approaches to photography have clearly had devastating effects, but they also are, in retrospect, demonstrably untrue and deliberately fictional. They reflect not only extreme political and cultural biases but also represent intentional campaigns to deceive and misrepresent through photography. What has interested me, especially in the work of contemporary photography over the last ten or twenty years, has been the conceptual endeavor by many photographers to try to undo the destruction done by these campaigns in the name of truth, to question critically the concepts of authorship, originality, quality, objectivity, and singularity. The gender biases of photography, the cultural biases of photography, the racial biases of photography, and the national biases of photography have created exclusions and invisibilities in information and histories.

Dawit Petros

Eritrean, born 1972

Exploring the dichotomy of presence and absence, Dawit Petros created a project called “Mimesis (The Woodstock Series)” during his 2007 residency. Using repetition as a formal device, Petros investigates personal and cultural memory, and the relationship between setting and subject–in this case, the artist himself. The title of this diptych, Support Structure as Me, emphasizes the artist’s presence in the first image and his absence in the second. One must wonder about the artist’s abrupt disappearance and its possible effect on the integrity of the structure that was bearing down on him. “The process of subsuming one’s self into an environment through the faculty of imitation,” says Petros, “raises questions of affinity and reciprocity between oneself and one’s context.”

Eritrean, born 1972

Exploring the dichotomy of presence and absence, Dawit Petros created a project called “Mimesis (The Woodstock Series)” during his 2007 residency. Using repetition as a formal device, Petros investigates personal and cultural memory, and the relationship between setting and subject–in this case, the artist himself. The title of this diptych, Support Structure as Me, emphasizes the artist’s presence in the first image and his absence in the second. One must wonder about the artist’s abrupt disappearance and its possible effect on the integrity of the structure that was bearing down on him. “The process of subsuming one’s self into an environment through the faculty of imitation,” says Petros, “raises questions of affinity and reciprocity between oneself and one’s context.”

TiP: I am very interested in the way photographs were used socially, because so many of these people who worked outside the fine-art approach to photography identified as community photographers. For them, it was not only the content of their photography that made them “community photographers,” it was the interaction they had with people, organizations, and social groups in their community. I'm hoping that through the way you're describing community in Kingston, you're trying to generate that level of interaction. Maybe what you’re describing is a new kind of museum.

Wallis: I think it’s clear that the role of the museum is a now contested one, a site of activist confrontation. In fact, that may be an understatement in our current situation. Not only professional critics, but audiences widely are questioning the motives, the funding, the histories, and the political and financial affiliations of museums. They are demanding to know why those factors make museum’s public presentations look a particular way and why those associations govern the types of questions that museums are asking. The whole nature of the museum as an institution, which in the past has been, I would say, predominantly elitist and anti-community, is one that is very much up for grabs these days. At the Center for Photography at Woodstock, we are trying to create what might be called an anti-museum, one that is more permeable within the community, which is establishing a basis for cultural interactions that break down a lot of the barriers that museums create, one that disqualifies a lot of the critical expectations that audience members might bring to a museum. Our goal is to create a space that's more like a community center: one that raises critical issues germane to various local audiences, that has shared spaces for meetings of local groups and cultural organizations, that has exhibitions of non-rarified cultural materials, that has communal film screenings and events, and that provides a hub or nucleus for issues and ideas that all have a cultural inflection, but might not be the kinds of Art–with a capital “A”--that one might find in another context.

Wallis: I think it’s clear that the role of the museum is a now contested one, a site of activist confrontation. In fact, that may be an understatement in our current situation. Not only professional critics, but audiences widely are questioning the motives, the funding, the histories, and the political and financial affiliations of museums. They are demanding to know why those factors make museum’s public presentations look a particular way and why those associations govern the types of questions that museums are asking. The whole nature of the museum as an institution, which in the past has been, I would say, predominantly elitist and anti-community, is one that is very much up for grabs these days. At the Center for Photography at Woodstock, we are trying to create what might be called an anti-museum, one that is more permeable within the community, which is establishing a basis for cultural interactions that break down a lot of the barriers that museums create, one that disqualifies a lot of the critical expectations that audience members might bring to a museum. Our goal is to create a space that's more like a community center: one that raises critical issues germane to various local audiences, that has shared spaces for meetings of local groups and cultural organizations, that has exhibitions of non-rarified cultural materials, that has communal film screenings and events, and that provides a hub or nucleus for issues and ideas that all have a cultural inflection, but might not be the kinds of Art–with a capital “A”--that one might find in another context.

Joanna Tam

American, born China, 1972

Joanna Tam’s series “Manner of Delivery” is a response to the way patriotism is transmitted during the immigrant naturalization process. During her 2013 residency, Tam made a series of self-portraits in which she holds her right hand over her heart in mundane settings. Taken out of context, the gesture appears strange, despite being the country’s most recognizable patriotic symbol. The series title comes from Title 4, Section 4 of the Code of Laws of the United States, which specifies the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag and its “manner of delivery.” Considered in light of recent anti-Asian violence, Tam’s work is a powerful challenge to the exclusion of minority ethnicities, and a looming demand that they demonstrate their loyalty at any given moment.

American, born China, 1972

Joanna Tam’s series “Manner of Delivery” is a response to the way patriotism is transmitted during the immigrant naturalization process. During her 2013 residency, Tam made a series of self-portraits in which she holds her right hand over her heart in mundane settings. Taken out of context, the gesture appears strange, despite being the country’s most recognizable patriotic symbol. The series title comes from Title 4, Section 4 of the Code of Laws of the United States, which specifies the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag and its “manner of delivery.” Considered in light of recent anti-Asian violence, Tam’s work is a powerful challenge to the exclusion of minority ethnicities, and a looming demand that they demonstrate their loyalty at any given moment.

TiP: The role of the museum is critical especially in the ways in which museums validate work. They define what is important and has cultural impact. And I think you're absolutely right that museums have tended to be anti-community engagement. I love the idea of opening it up so that there's a broader constituent base of work that is shown and people who come. But how can that be done effectively, with some curatorial focus and maintaining the museum’s educational role?

Wallis: One thing you said that struck me was about validation, and the role of a museum as a kind of gatekeeper or judgment seat. That makes me a little nervous. I do think that there is a way that museums can invert that expectation or capacity to validate by putting things in museums that are unexpected, more publicly accessible, more familiar to audiences as things that they might encounter in their everyday lives. For example, with vernacular photography, if you're exhibiting family photo albums, I think visitors to an exhibition can recognize and develop critical ideas about their own family photographs, about their attitudes toward photography or photographic truth, ideas that they may not have thought of before, or in exactly that way. So, for me, the defining role of the museum–or if you want to call it an anti-museum–is as a stimulator for discourse, a place for presenting objects and images that generate ideas in the minds of viewers, that initiate individual or collective conversations about the cultural impact of photography. That's really what interests me: the cultural impact of photography, how it shapes and distorts social representations and ideas.

Wallis: One thing you said that struck me was about validation, and the role of a museum as a kind of gatekeeper or judgment seat. That makes me a little nervous. I do think that there is a way that museums can invert that expectation or capacity to validate by putting things in museums that are unexpected, more publicly accessible, more familiar to audiences as things that they might encounter in their everyday lives. For example, with vernacular photography, if you're exhibiting family photo albums, I think visitors to an exhibition can recognize and develop critical ideas about their own family photographs, about their attitudes toward photography or photographic truth, ideas that they may not have thought of before, or in exactly that way. So, for me, the defining role of the museum–or if you want to call it an anti-museum–is as a stimulator for discourse, a place for presenting objects and images that generate ideas in the minds of viewers, that initiate individual or collective conversations about the cultural impact of photography. That's really what interests me: the cultural impact of photography, how it shapes and distorts social representations and ideas.

Xaviera Simmons

American, born 1974

Xaviera Simmons adopts in her self-portraits unyielding fictional identities to explore the intricate symbolism of the Black experience in America. Simmons often places herself in landscapes that complicate the traditional understanding of Black archetypes. In this work, for example, she appears barefoot and fatigued, trudging in front of a decrepit cabin in the woods, a bundle on a stick over her shoulder. Simmons here assumes the identity of a Reconstruction era sharecropper, referencing the postbellum American South when Black Americans discovered, to their horror, that any progress would be undone by the descending veil of Jim Crow. “How might our entire history have been different had America fulfilled its emancipatory promises to its freed slaves and their descendants,” says Simmons, “instead of commemorating its defeated Confederate planters?”

American, born 1974

Xaviera Simmons adopts in her self-portraits unyielding fictional identities to explore the intricate symbolism of the Black experience in America. Simmons often places herself in landscapes that complicate the traditional understanding of Black archetypes. In this work, for example, she appears barefoot and fatigued, trudging in front of a decrepit cabin in the woods, a bundle on a stick over her shoulder. Simmons here assumes the identity of a Reconstruction era sharecropper, referencing the postbellum American South when Black Americans discovered, to their horror, that any progress would be undone by the descending veil of Jim Crow. “How might our entire history have been different had America fulfilled its emancipatory promises to its freed slaves and their descendants,” says Simmons, “instead of commemorating its defeated Confederate planters?”

|

|

Delve deeper |