This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the PhotographerSusan Teegardin worked at Texas Monthly magazine, owned a gallery bookstore, DW Books, published photographs in National Lampoon and D Magazine, made videos as one of The Susans, and now does nothing but reading and gardening. |

|

Truth in Photography: Why did you start doing these little postcard books?

Susan Teegardin: Well, that's a good question. I'm having to go back way in the past to try to remember. I've always loved postcards and I collect postcards, and that may be why I did it. I do know what started me doing the Proof of Mondrian. I got that idea from the Church of the SubGenius, because they put out newsletters every once in a while. And their God is J. R. "Bob" Dobbs.

TiP: Where is the Church of SubGenius? Was that a Dallas, Texas thing?

Teegardin: Yeah, it just resided in Doug Smith’s head, and I think they used to have meetings and stuff.

TiP: What was it that they were doing that made you want to do this?

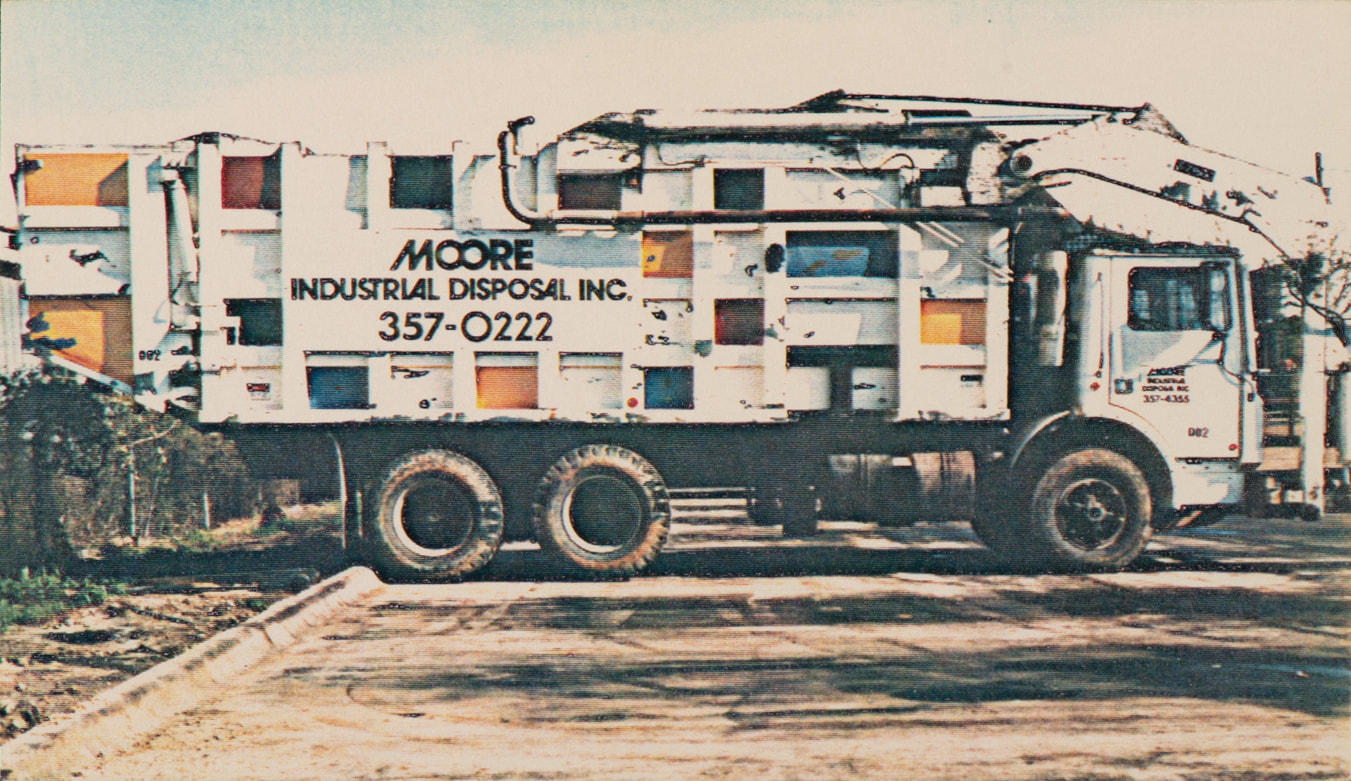

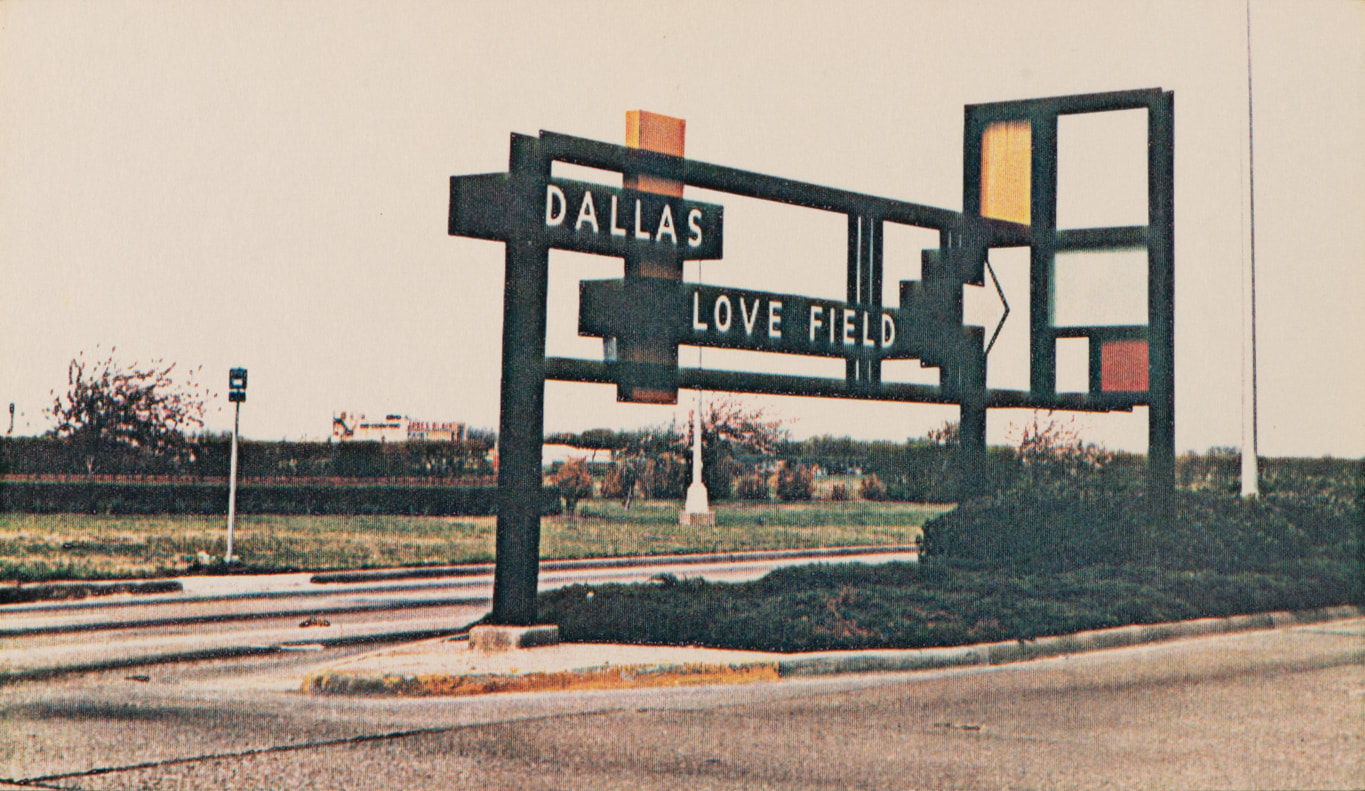

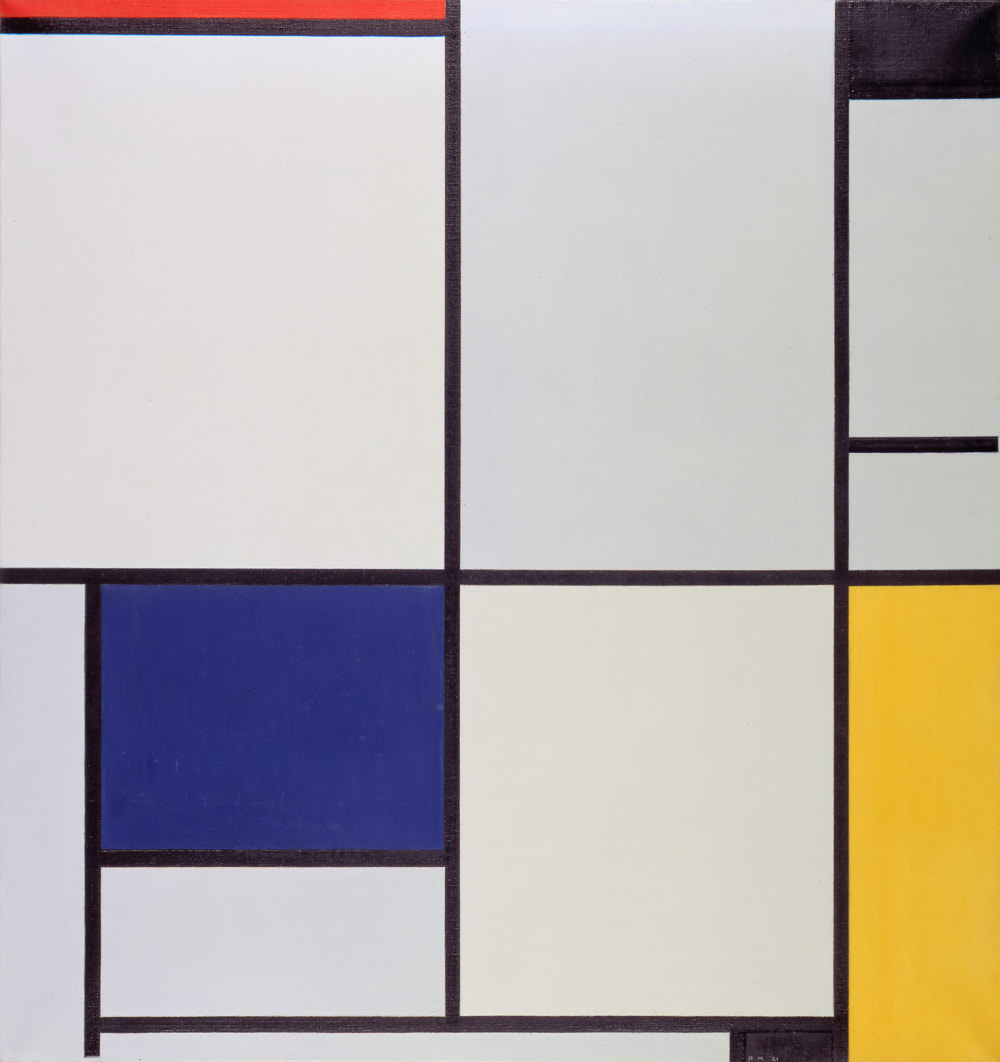

Teegardin: Well, in one of their newsletters, they had something called Proof of Bob, which I thought was just really funny, and they would show pictures of Bob. They were pictures of things like Bob's grocery store and things like that. And they would take a picture of it, and that was proof of Bob. So, I saw these things that look Mondrian-esque as I was driving around town. I think the first one was the entrance to Love Field, which is no longer there anymore, but it's in the series. And I just called it Proof of Mondrian. Anyway, that's where that title came from. And I don't know why I made postcards out of it, but I know I wanted to collect them. The Mondrian things I saw. One of them, especially, was of the great trash truck.

Susan Teegardin: Well, that's a good question. I'm having to go back way in the past to try to remember. I've always loved postcards and I collect postcards, and that may be why I did it. I do know what started me doing the Proof of Mondrian. I got that idea from the Church of the SubGenius, because they put out newsletters every once in a while. And their God is J. R. "Bob" Dobbs.

TiP: Where is the Church of SubGenius? Was that a Dallas, Texas thing?

Teegardin: Yeah, it just resided in Doug Smith’s head, and I think they used to have meetings and stuff.

TiP: What was it that they were doing that made you want to do this?

Teegardin: Well, in one of their newsletters, they had something called Proof of Bob, which I thought was just really funny, and they would show pictures of Bob. They were pictures of things like Bob's grocery store and things like that. And they would take a picture of it, and that was proof of Bob. So, I saw these things that look Mondrian-esque as I was driving around town. I think the first one was the entrance to Love Field, which is no longer there anymore, but it's in the series. And I just called it Proof of Mondrian. Anyway, that's where that title came from. And I don't know why I made postcards out of it, but I know I wanted to collect them. The Mondrian things I saw. One of them, especially, was of the great trash truck.

TiP: Do you feel that the postcards that you made are true representations of what you saw in the world?

Teegardin: Yes, they were. And are they true representations? I don't know. I've never considered that. I mean, they have to be. The ones I collected were photographs. To me, those are true representations.

TiP: Would you say that your approach to photography is more spontaneous?

Teegardin: No, it's more than that. It's not really spontaneous, but my sense of composition is not thought out. It’s just unconscious.

TiP: What's the intent of these postcards? Is it purely aesthetic?

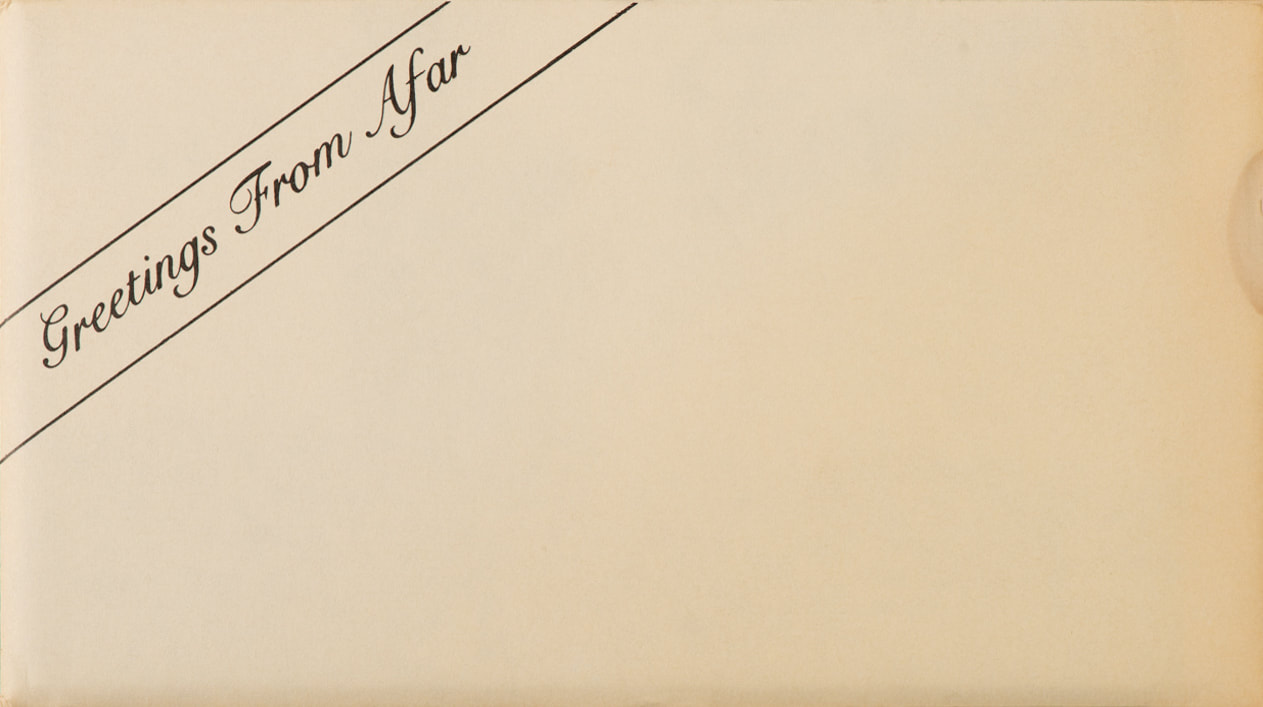

Teegardin: Well, I mean, it's really a document. It's a document of the underlying idea of what I'm trying to show. For instance, there's a title like Greetings from Afar. The names are the most important thing because that's what it's all about. And, once that is fixed, once I have that in my lens and the way I want to see it, which is just to make it clear, and to highlight it more than anything, then I look at what's around it and just try to make a good picture out of it, that's all. It's both trying to focus on the name, then trying to make it an interesting picture with the name in it. But the name is most important. However, the stuff that's around the name is also very telling, and that's why I also include that.

Teegardin: Yes, they were. And are they true representations? I don't know. I've never considered that. I mean, they have to be. The ones I collected were photographs. To me, those are true representations.

TiP: Would you say that your approach to photography is more spontaneous?

Teegardin: No, it's more than that. It's not really spontaneous, but my sense of composition is not thought out. It’s just unconscious.

TiP: What's the intent of these postcards? Is it purely aesthetic?

Teegardin: Well, I mean, it's really a document. It's a document of the underlying idea of what I'm trying to show. For instance, there's a title like Greetings from Afar. The names are the most important thing because that's what it's all about. And, once that is fixed, once I have that in my lens and the way I want to see it, which is just to make it clear, and to highlight it more than anything, then I look at what's around it and just try to make a good picture out of it, that's all. It's both trying to focus on the name, then trying to make it an interesting picture with the name in it. But the name is most important. However, the stuff that's around the name is also very telling, and that's why I also include that.

TiP: So in all of these instances, you decide on your title first, the concept.

Teegardin: Yes, the concept, yes. They're illustrating a concept that is true.

TiP: If you were to complete the sentence, truth in photography is…?

Teegardin: I can't finish that sentence. I don’t know that I relate to that as a concept, because truth doesn't have that much to do with photography. Except in as much that a photograph is a true representation of what the lens was pointed at.

TiP: When you made these in the 1980s, I don't think that photography was being seen as a medium of manipulation in the way it is today.

Teegardin: No, not nearly as there is today.

TiP: There was no Photoshop. You could print differently. How did you make these? Did you print them or were they printed on postcard stock?

Teegardin: The Mondrian series are color xerox glued onto some heavy card stock. The b&w series were printed by a commercial printer.

TiP: In some sense, the object is a faux object. It's like a faux postcard with a real image.

Teegardin: Yeah, right. But I did make them so you could send them if you wanted to (well, not the Mondrians), so they were only partially faux.

TiP: Now, of course, we have cell phones, so you just take a cell phone picture and send that. I think there was a time that it was fun to stop in little places, buy funny postcards, or interesting ones of the place, and send them to your family or friends.

Teegardin: Oh, absolutely. That was one of the points of travel, was to get these postcards and send them to people. I love them. I had to go places to find postcards to send to people. I actively sought them out. I didn't just get them in a gift shop at the airport, although I did that too.

TiP: The act of buying a postcard and sending it is saying, “This is true.” It might be stylized, it might be colorized, but at the same time, you're sending it to somebody to say, “This is how it was.”

Teegardin: “I was here.” Depending on who I was sending it to, it was not always, “I was here.” A lot of times it would be the aesthetics of the postcard, that was the point of the postcard. It wasn't the place it was depicting, or what it was depicting. I had different intentions in sending the postcards. So, to somebody that knew I collected postcards of anonymous buildings, if I found an anonymous building, I might send that. I don't know what I would say on the back of the postcard, but they would just have to make of it what they would.

TiP: Well, it's interesting to play with that form because postcards, now, they're more artifacts. You still see them everywhere. I can't remember the last time I sent a postcard.

Teegardin: No. I have a friend who sends me postcards, but she knows she's doing a retro thing, you know? I mean, that's part of the point is, look, I'm sending you a postcard like we used to do.

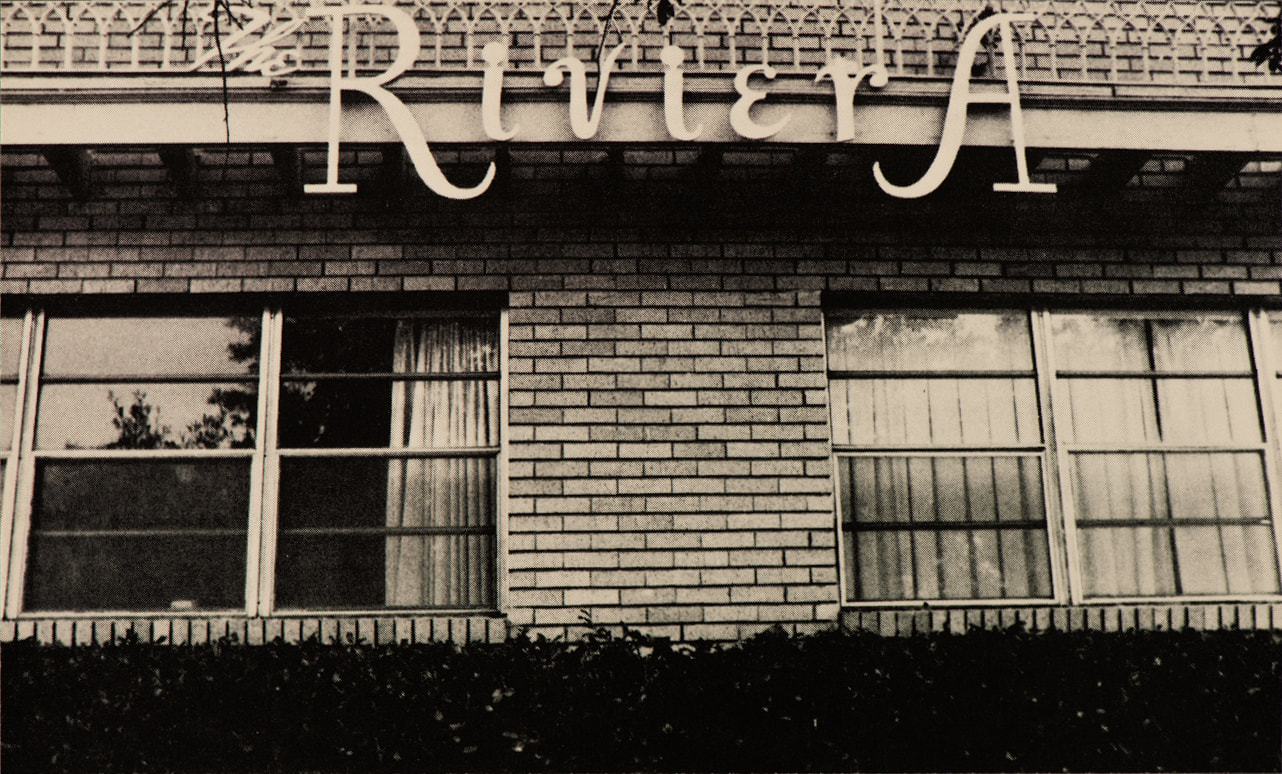

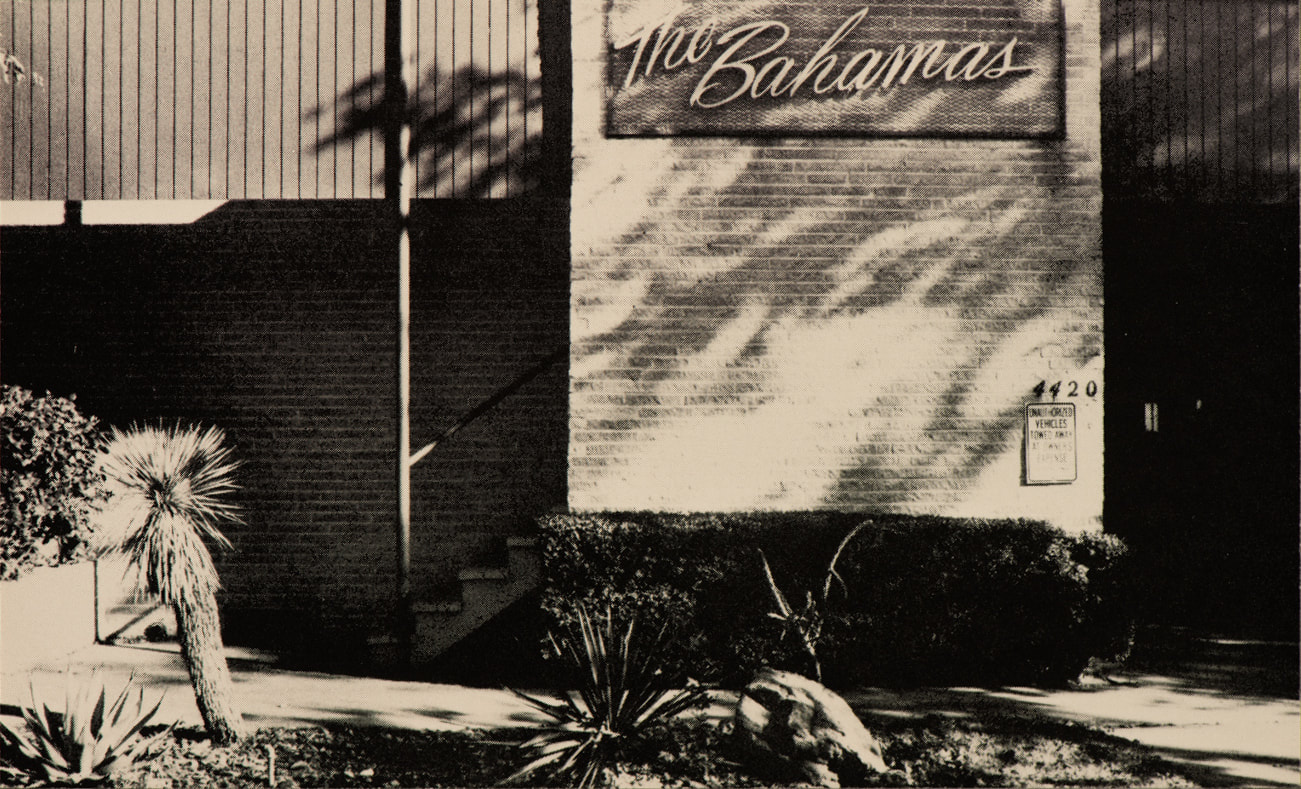

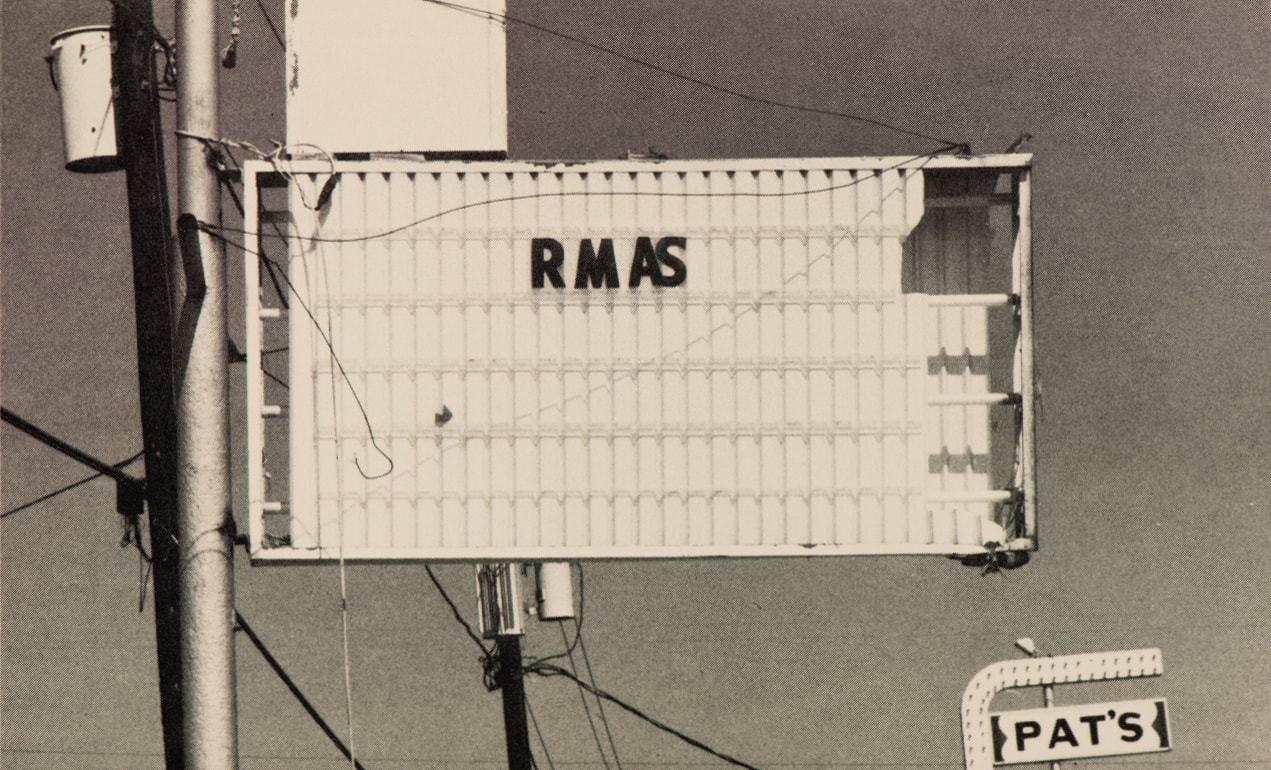

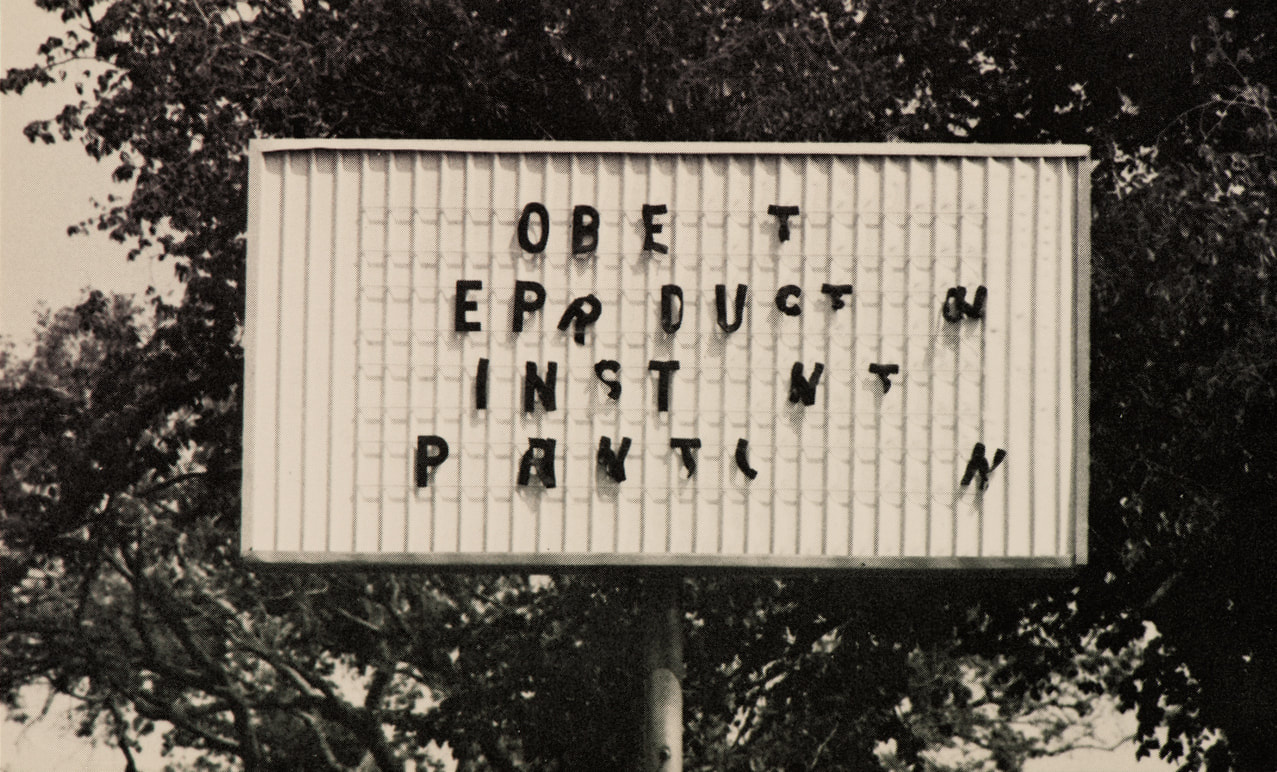

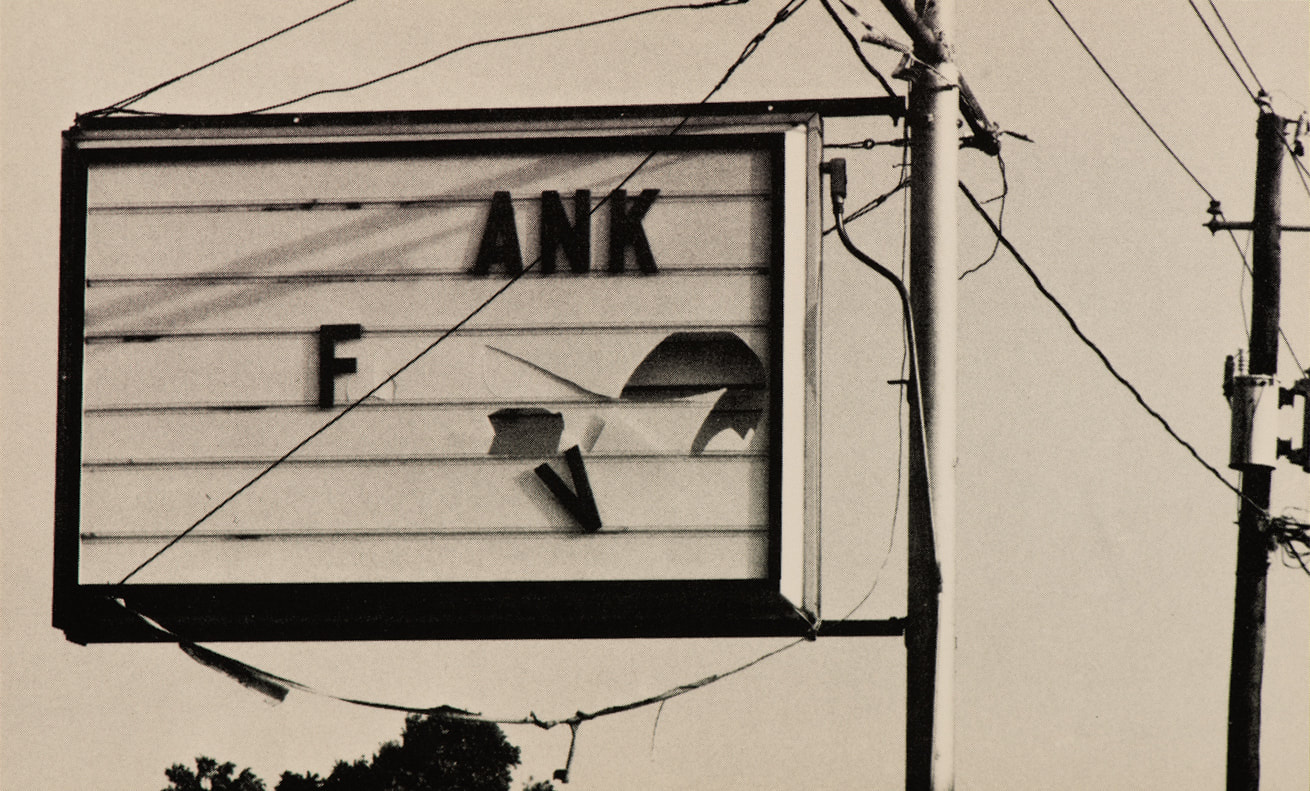

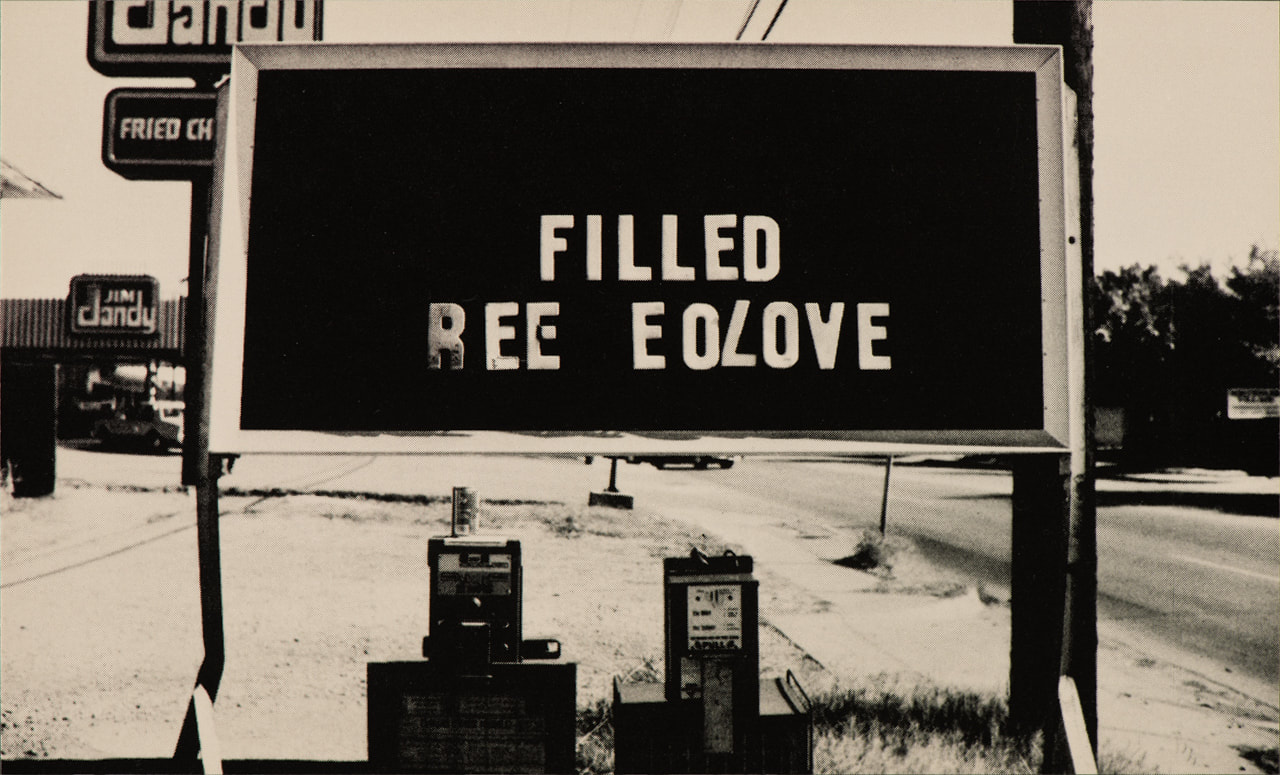

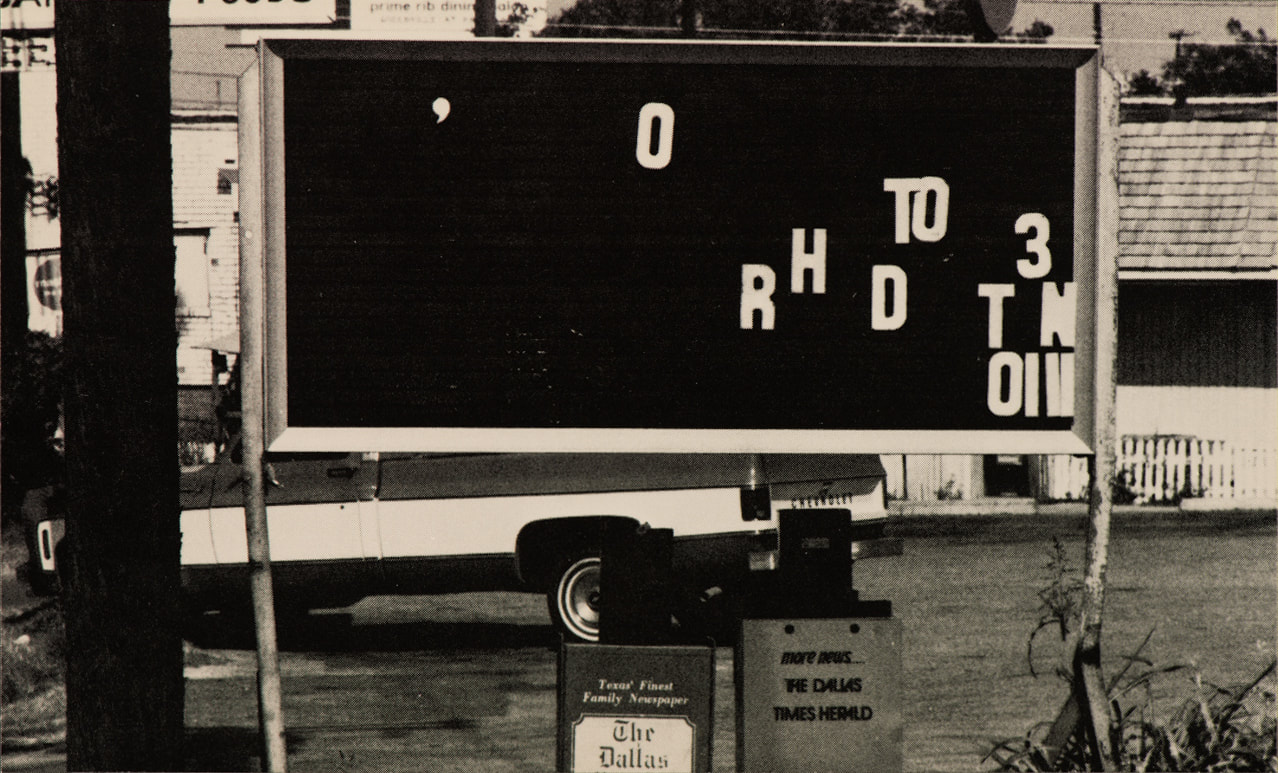

TiP: Talk about the Sign Language series.

Teegardin: Oh, that's the most one dimensional of them. I mean, in terms of taking the photos, the point of those was just to show them. I just tried to make it most clear what they looked like.

Teegardin: Yes, the concept, yes. They're illustrating a concept that is true.

TiP: If you were to complete the sentence, truth in photography is…?

Teegardin: I can't finish that sentence. I don’t know that I relate to that as a concept, because truth doesn't have that much to do with photography. Except in as much that a photograph is a true representation of what the lens was pointed at.

TiP: When you made these in the 1980s, I don't think that photography was being seen as a medium of manipulation in the way it is today.

Teegardin: No, not nearly as there is today.

TiP: There was no Photoshop. You could print differently. How did you make these? Did you print them or were they printed on postcard stock?

Teegardin: The Mondrian series are color xerox glued onto some heavy card stock. The b&w series were printed by a commercial printer.

TiP: In some sense, the object is a faux object. It's like a faux postcard with a real image.

Teegardin: Yeah, right. But I did make them so you could send them if you wanted to (well, not the Mondrians), so they were only partially faux.

TiP: Now, of course, we have cell phones, so you just take a cell phone picture and send that. I think there was a time that it was fun to stop in little places, buy funny postcards, or interesting ones of the place, and send them to your family or friends.

Teegardin: Oh, absolutely. That was one of the points of travel, was to get these postcards and send them to people. I love them. I had to go places to find postcards to send to people. I actively sought them out. I didn't just get them in a gift shop at the airport, although I did that too.

TiP: The act of buying a postcard and sending it is saying, “This is true.” It might be stylized, it might be colorized, but at the same time, you're sending it to somebody to say, “This is how it was.”

Teegardin: “I was here.” Depending on who I was sending it to, it was not always, “I was here.” A lot of times it would be the aesthetics of the postcard, that was the point of the postcard. It wasn't the place it was depicting, or what it was depicting. I had different intentions in sending the postcards. So, to somebody that knew I collected postcards of anonymous buildings, if I found an anonymous building, I might send that. I don't know what I would say on the back of the postcard, but they would just have to make of it what they would.

TiP: Well, it's interesting to play with that form because postcards, now, they're more artifacts. You still see them everywhere. I can't remember the last time I sent a postcard.

Teegardin: No. I have a friend who sends me postcards, but she knows she's doing a retro thing, you know? I mean, that's part of the point is, look, I'm sending you a postcard like we used to do.

TiP: Talk about the Sign Language series.

Teegardin: Oh, that's the most one dimensional of them. I mean, in terms of taking the photos, the point of those was just to show them. I just tried to make it most clear what they looked like.

TiP: Frequently, they’re not saying anything, because parts of them are missing.

Teegardin: Well, that's what I mean. That was the whole point of it, is that they are signs that were supposed to say something, but they actually said nothing. But that was the point when I took them, because they were meant to, and they imparted no meaning.

TiP: There's a certain truth in the photograph being real and factual. But in fact, what it's showing is not factual or real, in a sense, because it's not the way it was originally made. The letters fallen out of these signs were not intentional.

Teegardin: But the photographs themselves were factual. The photographs themselves didn’t care what they were intended to be. Although it does get a little murky here, since the point was they weren’t fulfilling their intention. But I was making the point, not the photographs. They were just showing what was there.

TiP: It’s sort of indiscernible.

Teegardin: I didn't even try to figure out what they were saying, though, because I really didn't care. What was important was that they were saying nothing. In terms of taking the picture, the way they looked compositionally was not of interest to me. The point was simply to focus on the sign itself and have it be clear in terms of the photograph, not what it was saying, but just to show it. I wanted people to see it as I saw it and to wonder at it as I wondered at it.

Teegardin: Well, that's what I mean. That was the whole point of it, is that they are signs that were supposed to say something, but they actually said nothing. But that was the point when I took them, because they were meant to, and they imparted no meaning.

TiP: There's a certain truth in the photograph being real and factual. But in fact, what it's showing is not factual or real, in a sense, because it's not the way it was originally made. The letters fallen out of these signs were not intentional.

Teegardin: But the photographs themselves were factual. The photographs themselves didn’t care what they were intended to be. Although it does get a little murky here, since the point was they weren’t fulfilling their intention. But I was making the point, not the photographs. They were just showing what was there.

TiP: It’s sort of indiscernible.

Teegardin: I didn't even try to figure out what they were saying, though, because I really didn't care. What was important was that they were saying nothing. In terms of taking the picture, the way they looked compositionally was not of interest to me. The point was simply to focus on the sign itself and have it be clear in terms of the photograph, not what it was saying, but just to show it. I wanted people to see it as I saw it and to wonder at it as I wondered at it.