|

|

About the ArtistA photographer and artist, Nigel Poor lives and works in the Bay Area. She is a Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento. She taught a history of photography class for the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison. She is the co-founder of the podcast Ear Hustle, which features stories from both inside prison and from the outside, post-incarceration. Her book The San Quentin Project is published by Aperture. |

|

Truth in Photography: What prompted you to start going to San Quentin?

Nigel Poor: I heard a news story on NPR about a prison in Saint Petersburg called Kresty Prison. The story was about how overcrowded it was, and it was this terrible place to be, and that as a way to make money the prison was being opened up as a place for tourists to go. They could walk by people in cells and end up in a gift store and buy things, crafts that were made by the people that were incarcerated there. It really scared me. It just seemed like this horrible, horrible thing that prisons could become a tourist destination. I got really obsessed with going to Russia because I wanted to see it. I was able to visit Saint Petersburg, and I had a really hard time finding the prison. Everyone I asked seemed like they didn’t know where it was. The last day I was there, I was leaving on the train to go back to Finland, and it turned out the prison was right next to the train station. So I was walking around it, and unlike prisons in the United States, you could walk right up to it. It didn’t seem like there were any fences there. It was so strange, and on the ground were all these really weird cone shaped objects. They were about eight inches long, and they were paper with this little brown stuff at the end. There were dozens all over the place, and so I took one with me. When I got home, I started researching it. I found out that the people inside the prison write notes, and they throw them out the window. To me it was this really interesting gesture. You’re in this horrible dehumanized space, and yet you’re trying to figure out a way to communicate with the outside world. So that got me thinking more about prisons. Then, I started getting mail delivered to my house from San Quentin. It wasn’t to me, it was misdelivered to my house, and I got it three times. So that was like another thing, like, “Oh, I need to find out more about prisons.” Then I found out about the Prison University Project at San Quentin, which at the time was the only on-site degree-granting program in California. They were looking for volunteers to teach an art class. That was the third thing, so I started volunteering.

TiP: You were teaching about photography?

Poor: At first I thought I was going to be teaching photography. I didn’t know a lot about prisons. It soon became clear to me that, no, I wasn’t going to be teaching photography. They were looking for someone to teach a history class. I teach a history of photography class at my university, and so that’s what I did. I taught an amended version of the photography class that I taught at Sacramento State. I assumed I could just teach the class that I’d been teaching for a while, but I was told through the Prison University Project, the administration had made it clear that they were really concerned about what kind of imagery I would be showing. They said that there couldn’t be any images of sex, drug use, violence, or provocative imagery. So for me that was like ninety percent of photography was going to be off the table. So Jody Lewen, who is the Executive Director of the Prison University Project [now called Mount Tamalpais College] arranged a meeting for me with the assistant warden and the secretary of the California Department of Corrections to talk about the class I was going to teach. I put together a presentation, and I met with them, which I thought was going to be for about a half an hour. We ended up talking for about three hours, and I basically gave them a history of photography class. They were super intrigued, and they ended up letting me bring in almost all of the images I wanted to bring in, except a few that had images of children in them. It was a really good example to me of how photography actually can bridge a gap between people. Whether it’s true or not, it is a good vehicle for conversation.

Nigel Poor: I heard a news story on NPR about a prison in Saint Petersburg called Kresty Prison. The story was about how overcrowded it was, and it was this terrible place to be, and that as a way to make money the prison was being opened up as a place for tourists to go. They could walk by people in cells and end up in a gift store and buy things, crafts that were made by the people that were incarcerated there. It really scared me. It just seemed like this horrible, horrible thing that prisons could become a tourist destination. I got really obsessed with going to Russia because I wanted to see it. I was able to visit Saint Petersburg, and I had a really hard time finding the prison. Everyone I asked seemed like they didn’t know where it was. The last day I was there, I was leaving on the train to go back to Finland, and it turned out the prison was right next to the train station. So I was walking around it, and unlike prisons in the United States, you could walk right up to it. It didn’t seem like there were any fences there. It was so strange, and on the ground were all these really weird cone shaped objects. They were about eight inches long, and they were paper with this little brown stuff at the end. There were dozens all over the place, and so I took one with me. When I got home, I started researching it. I found out that the people inside the prison write notes, and they throw them out the window. To me it was this really interesting gesture. You’re in this horrible dehumanized space, and yet you’re trying to figure out a way to communicate with the outside world. So that got me thinking more about prisons. Then, I started getting mail delivered to my house from San Quentin. It wasn’t to me, it was misdelivered to my house, and I got it three times. So that was like another thing, like, “Oh, I need to find out more about prisons.” Then I found out about the Prison University Project at San Quentin, which at the time was the only on-site degree-granting program in California. They were looking for volunteers to teach an art class. That was the third thing, so I started volunteering.

TiP: You were teaching about photography?

Poor: At first I thought I was going to be teaching photography. I didn’t know a lot about prisons. It soon became clear to me that, no, I wasn’t going to be teaching photography. They were looking for someone to teach a history class. I teach a history of photography class at my university, and so that’s what I did. I taught an amended version of the photography class that I taught at Sacramento State. I assumed I could just teach the class that I’d been teaching for a while, but I was told through the Prison University Project, the administration had made it clear that they were really concerned about what kind of imagery I would be showing. They said that there couldn’t be any images of sex, drug use, violence, or provocative imagery. So for me that was like ninety percent of photography was going to be off the table. So Jody Lewen, who is the Executive Director of the Prison University Project [now called Mount Tamalpais College] arranged a meeting for me with the assistant warden and the secretary of the California Department of Corrections to talk about the class I was going to teach. I put together a presentation, and I met with them, which I thought was going to be for about a half an hour. We ended up talking for about three hours, and I basically gave them a history of photography class. They were super intrigued, and they ended up letting me bring in almost all of the images I wanted to bring in, except a few that had images of children in them. It was a really good example to me of how photography actually can bridge a gap between people. Whether it’s true or not, it is a good vehicle for conversation.

TiP: Why aren’t cameras allowed for prisoners?

Poor: I think because people are afraid of the power of the image and what would be seen if people inside could have a camera. It’s very hard to control. I do think most people have an innate desire to document what’s happening in their lives, good or bad. If people inside prisons had cameras, it might be pretty shocking what we would see. I think we would see all kinds of stuff, but we would probably see images that are really upsetting.

TiP: Were you able to photograph inmates?

Poor: I photographed inside and I’ve done pictures for the Ear Hustle podcast, but in terms of doing a serious endeavor that I would find sustaining, I realized that for myself taking photographs was not going to be it. I didn’t know what I would do that hadn’t been done before, and I also felt like it just wasn’t my place to go in and photograph. It just didn’t work for me. So I wanted to find ways to do more collaborative projects. In the class, even though it was a history class, I wanted students to get the idea of making, what the power of making and being creative can do for an individual’s mind and spirit, and how freeing it could be. So along with my colleague Doug Dertinger, who co-taught the class with me, we came up with assignments that required the same muscle that it requires to make a photograph, even though they were working without a camera. For example, one of the assignments we had was called “the verbal photograph.” We asked students to think about something that happened in their lives that they didn’t have a photograph of. Take that memory that’s like a film and distill it down to one image, and then write about that image as if they were looking at a photograph. Use photographic language, like perspective, scale, color, depth of field. It was really wonderful, and it helped people bring the chaos of memory down to one moment. There’s a beautiful one in the book. One of my student’s wrote about being a young child, and looking up and seeing his mother looking over his bed, and she has a slip on, and he can see her bangles, and there’s a cross on the wall. Then at the end of the essay, he says that, “This is the first memory of my mother, or it’s what I perceive to be the first memory of my mother. I’m not sure what the truth is.” He understood how photography works, that it isn’t about truth, it’s the fact and fiction again mingling together, and it’s also our desire to have a memory.

TiP: How did you gain access to the photographic archives of San Quentin?

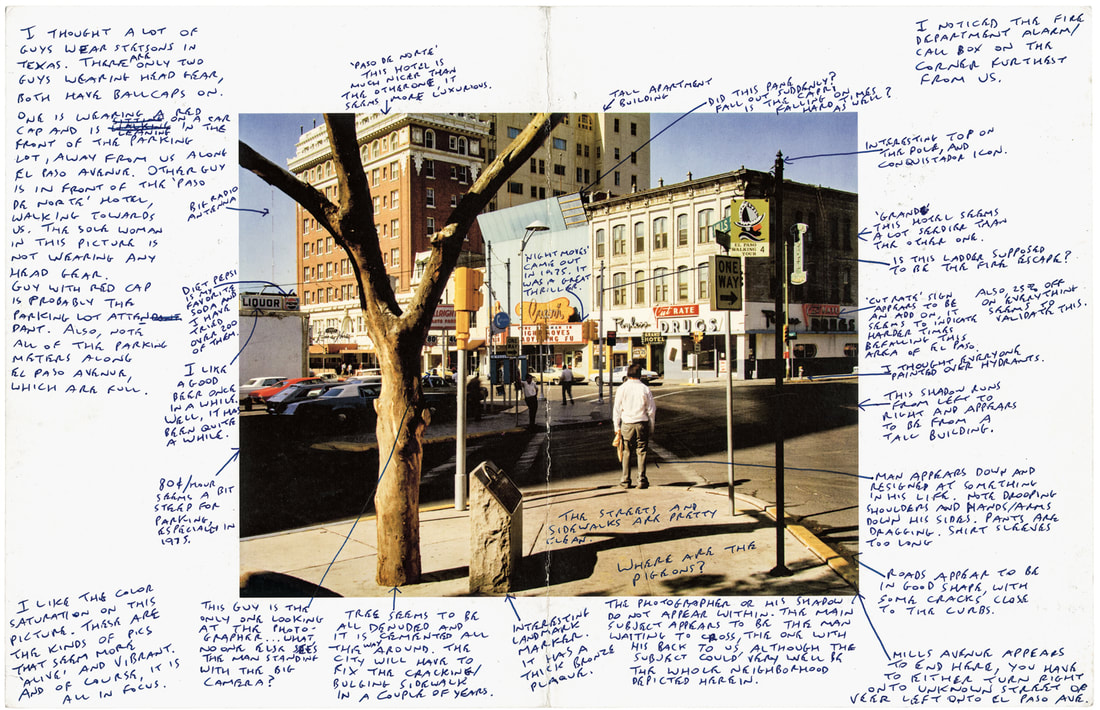

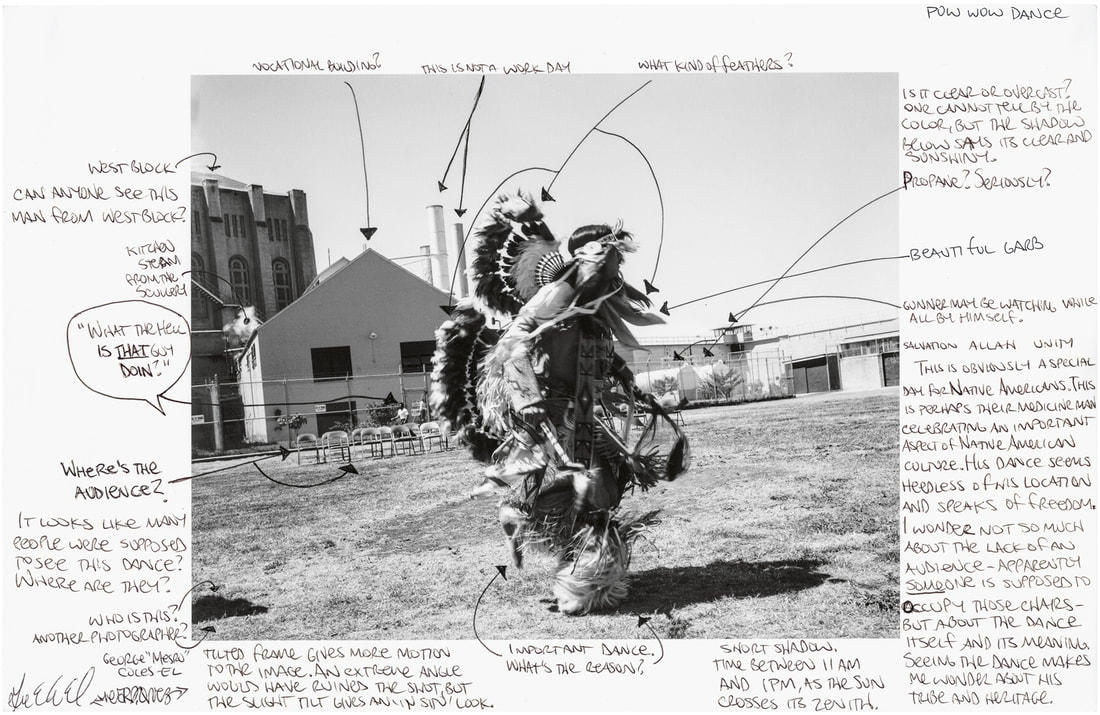

Poor: It happened just by chance. There was another assignment that we were doing in the class, which was giving students images by well-known photographers and asking them to do what I was calling “mapping” the photograph. We printed the image on two sides. On one side we would ask them to annotate the photograph, to circle things, point out stuff that was curious to them, try to dissect what was happening in the photograph. Then they would take their mapping, and on the other side write a narrative based on the photograph and their understanding of the photograph.

Poor: I think because people are afraid of the power of the image and what would be seen if people inside could have a camera. It’s very hard to control. I do think most people have an innate desire to document what’s happening in their lives, good or bad. If people inside prisons had cameras, it might be pretty shocking what we would see. I think we would see all kinds of stuff, but we would probably see images that are really upsetting.

TiP: Were you able to photograph inmates?

Poor: I photographed inside and I’ve done pictures for the Ear Hustle podcast, but in terms of doing a serious endeavor that I would find sustaining, I realized that for myself taking photographs was not going to be it. I didn’t know what I would do that hadn’t been done before, and I also felt like it just wasn’t my place to go in and photograph. It just didn’t work for me. So I wanted to find ways to do more collaborative projects. In the class, even though it was a history class, I wanted students to get the idea of making, what the power of making and being creative can do for an individual’s mind and spirit, and how freeing it could be. So along with my colleague Doug Dertinger, who co-taught the class with me, we came up with assignments that required the same muscle that it requires to make a photograph, even though they were working without a camera. For example, one of the assignments we had was called “the verbal photograph.” We asked students to think about something that happened in their lives that they didn’t have a photograph of. Take that memory that’s like a film and distill it down to one image, and then write about that image as if they were looking at a photograph. Use photographic language, like perspective, scale, color, depth of field. It was really wonderful, and it helped people bring the chaos of memory down to one moment. There’s a beautiful one in the book. One of my student’s wrote about being a young child, and looking up and seeing his mother looking over his bed, and she has a slip on, and he can see her bangles, and there’s a cross on the wall. Then at the end of the essay, he says that, “This is the first memory of my mother, or it’s what I perceive to be the first memory of my mother. I’m not sure what the truth is.” He understood how photography works, that it isn’t about truth, it’s the fact and fiction again mingling together, and it’s also our desire to have a memory.

TiP: How did you gain access to the photographic archives of San Quentin?

Poor: It happened just by chance. There was another assignment that we were doing in the class, which was giving students images by well-known photographers and asking them to do what I was calling “mapping” the photograph. We printed the image on two sides. On one side we would ask them to annotate the photograph, to circle things, point out stuff that was curious to them, try to dissect what was happening in the photograph. Then they would take their mapping, and on the other side write a narrative based on the photograph and their understanding of the photograph.

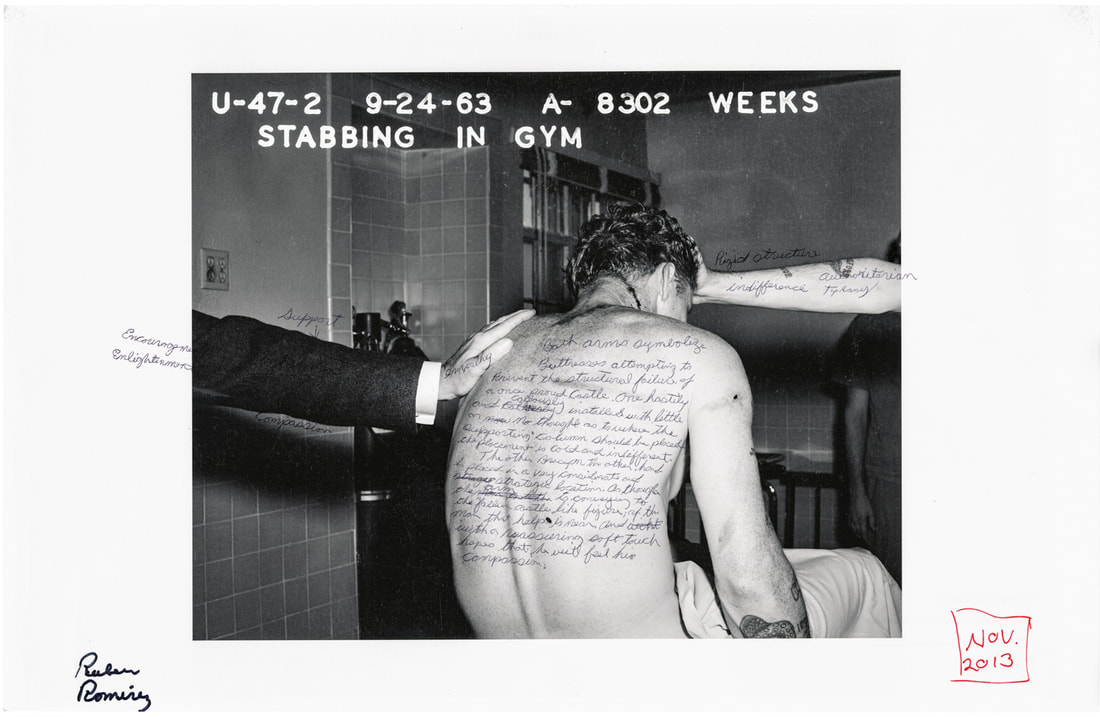

I’d been going into San Quentin for probably about a year and a half, almost two years, and I started volunteering in the media lab working on a radio project. Through that I got to know Lieutenant Sam Robinson, who is the public information officer. I knew I wanted to do more projects inside the prison, and it was very clear to me, in order to do that, you need to get to know not only the men inside, but also the administration. So I would visit Lieutenant Robinson a lot, and he knew I was a photographer. One day I was in his office, and I noticed on his desk he had an 11x14 box of old Kodak color paper. I asked him what it was, and he said, “Oh, you’re going to love these.” And he opened the box, and they were aerial photos of San Quentin, probably from the ’70s. They were okay, but they weren’t really amazing photographic specimens. But I commented that I was interested, and he said, “Well, if you like those, you’re going to love this.” He literally picked up his banker’s box that was underneath his desk, and he took the top off, and I looked inside. This still makes me emotional. There were hundreds and hundreds of 4x5 negatives. Without seeing any more than that, I could see they were old, I knew this was something amazing. He said they’d been taken at San Quentin, and I started looking through them. It was any archivist, or photographer, or curious person’s dream of finding a mystery.

|

As I started looking through the pictures in his office, I could see they were pictures of murders, and gatherings, and cells, and accidents. I asked him if I could take some home and scan them, and he said yes, which is shocking. So I took an envelope of maybe thirty negatives home. I scanned them and I brought them back to him, and he was really interested when he saw the prints. I just said, “You know what, can I just do something with this?” They were just moldering away. These are clearly important historic documents, and they should be protected. I said, “Can I just scan them and preserve them?” Again, he said yes, which was shocking. So he just gave me this huge box of thousands and thousands of negatives. I spent years going through them, archiving them, putting them in archival protection. Then I wanted to try to do some interactive project with the men inside, and he gave me permission to start an informal photography group. We were probably like 8-12 guys, and we would meet a couple times a month and look at the photographs, and then do the mapping exercises. It was all based on a serendipitous interaction, and me asking a question and being curious. I always tell my students, asking questions, and actually listening to what people have to tell you, is one of the best ways you can move forward in the world. Because you never know what’s going to happen. You just always have to put yourself in a place of not knowing, and then kind of accept what’s coming your way.

|

TiP: You have a very successful podcast, Ear Hustle. Is there a disconnect or a jump between audio and photography, or are they, in your mind, connected?

Poor: People wonder, and I wondered at first, being a photographer, how could I make the transition to doing audio? Is there any kind of connection? Are they completely different worlds? And for me, photography is about storytelling. It’s about listening and looking and being open to what comes your way, and not judging, and looking again for how the fact and fiction are going to come together in an image. I took all of that, that I’d been thinking about for the last thirty years, and applied that to storytelling through audio. I think it was a very easy transition actually. Yes, there are new technical skills you have to learn, but being present to witness what is happening around you, and to collaborate with people, was the skill. That’s what I used in photography, and that’s what I use in audio. I will say that I’m doing a lot less photography now, because audio has taken over my life, but I feel like it’s exercising the same muscles for sure.

Poor: People wonder, and I wondered at first, being a photographer, how could I make the transition to doing audio? Is there any kind of connection? Are they completely different worlds? And for me, photography is about storytelling. It’s about listening and looking and being open to what comes your way, and not judging, and looking again for how the fact and fiction are going to come together in an image. I took all of that, that I’d been thinking about for the last thirty years, and applied that to storytelling through audio. I think it was a very easy transition actually. Yes, there are new technical skills you have to learn, but being present to witness what is happening around you, and to collaborate with people, was the skill. That’s what I used in photography, and that’s what I use in audio. I will say that I’m doing a lot less photography now, because audio has taken over my life, but I feel like it’s exercising the same muscles for sure.

|

TiP: How much do you know about the photographers of the prison photographs? They were made by correctional officers?

Poor: I know very little. They were made by correctional officers, but from photographs I can also see that some of the people who were incarcerated at the time were working with these correctional officers, and were trained to use these field cameras, 4x5 cameras. I think it’s a combination, but primarily correctional officers. But I don’t know the names. I don’t know who any of them are. The photographs are from the late 1930s to the early ’80s, and of course some of those people could still be alive, but I’ve never met anyone, and nobody seems to know who the photographers were. Now somebody could spend some time and probably solve that mystery, but it’s not the lane I went down. So to me, they’re anonymous. TiP: What about the subjects? Are they known? Poor: The negatives were housed in those yellow 4x5 inch negative holders. Some of them have the name of the person in the photograph and their CDCR [California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation] number. So I could look them up. I have chosen not to do that, and I’ve taken out numbers so people can’t be identified. |

TiP: What about publishing them, is that an issue?

Poor: Is it an ethical issue to do this work? I’ve thought about it a lot, obviously. I think that I have to put the images in the context of when they were made. Unfortunately, when you go into prison, you lose your right to privacy. A lot of the people in these photographs did not give their permission to have the photographs taken. That’s certainly problematic, but the way I justify it is that we as taxpayers keep prisons open. Our taxes go to keep prisons open, and because of that we have a right to know what happens inside prisons. Seeing the historic photographs is one way we gain an understanding of what happens inside prison. So I weight those two things, and for me the ability to see inside, and hopefully change our opinions about how prison should function is worth putting these photographs out.

TiP: In what ways do you feel these photographs reveal truth?

Poor: Is it an ethical issue to do this work? I’ve thought about it a lot, obviously. I think that I have to put the images in the context of when they were made. Unfortunately, when you go into prison, you lose your right to privacy. A lot of the people in these photographs did not give their permission to have the photographs taken. That’s certainly problematic, but the way I justify it is that we as taxpayers keep prisons open. Our taxes go to keep prisons open, and because of that we have a right to know what happens inside prisons. Seeing the historic photographs is one way we gain an understanding of what happens inside prison. So I weight those two things, and for me the ability to see inside, and hopefully change our opinions about how prison should function is worth putting these photographs out.

TiP: In what ways do you feel these photographs reveal truth?

|

Poor: (reply in video)

|

|

TiP: The main motivation for the correctional officers who made the photographs was evidence. Do you feel that the photographs are also a kind of citizen journalism?

Poor: I never thought that, but what I have thought about is that looking at some of the photographs and seeing how they are composed, and seeing how they stray from the typical images of violence and depravation in prison, what I see is not the journalism. I see a desire to look as an artist, and to look beyond documenting depravation. So what I realized is that the camera gave some of these people permission to go outside what they were required to do, which is to document what was happening, and they started looking at what life was like in prison. If you didn’t know it was prison, some of them would look like any pictures from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. That’s what I notice, more than the journalism: this idea that the camera seduced them to see their surroundings in a different way, in some ways to lower their guard just a little bit. That’s to me also one of the mysteries of the archive. What I love about it is that there are really beautiful images in it of life. There are upsetting images that will haunt you, and then there are also just beautiful images of being a human.

Poor: I never thought that, but what I have thought about is that looking at some of the photographs and seeing how they are composed, and seeing how they stray from the typical images of violence and depravation in prison, what I see is not the journalism. I see a desire to look as an artist, and to look beyond documenting depravation. So what I realized is that the camera gave some of these people permission to go outside what they were required to do, which is to document what was happening, and they started looking at what life was like in prison. If you didn’t know it was prison, some of them would look like any pictures from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. That’s what I notice, more than the journalism: this idea that the camera seduced them to see their surroundings in a different way, in some ways to lower their guard just a little bit. That’s to me also one of the mysteries of the archive. What I love about it is that there are really beautiful images in it of life. There are upsetting images that will haunt you, and then there are also just beautiful images of being a human.

|

|

|