This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the ArtistAikaterini Gegisian is a visual artist and researcher of Greek-Armenian heritage. Her expanded photographic and moving image practice examines the role of diverse image histories in the production of gender and cultural identities. In 2023 she will premiere Third Person (Plural), her first feature length film and eponymous book (published by MACK); a long-term archival project based on a collection of two hundred post-war informational films and newsreels sourced from the Library of Congress and the American National Archives. In 2020, MACK published her collage photobook Handbook of the Spontaneous Other, which received international acclaim. In 2015, she was one of the exhibiting artists at the Armenian Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale, who received the Golden Lion for best national participation. She has been awarded the Nagoya University Award in 2001, and she was shortlisted for the First Book Award in 2015. In 2016, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art organized the first survey of her moving image practice. Gegisian received a BA in Critical Fine Art Practice by the University of Brighton, an MA in Fine Art by Chelsea College of Art and Design, and a PhD by Practice by the University of Westminster. Her works have been presented at numerous exhibitions, museums, galleries, and festivals, and are included in prominent private and museum collections. She lives between London and Thessaloniki and teaches at London Metropolitan University. Her work can be seen in the exhibition Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy, on view at the International Center of Photography from June 1 – September 11, 2023. |

|

Truth in Photography: Talk about the process of what you photograph and then how it becomes collage.

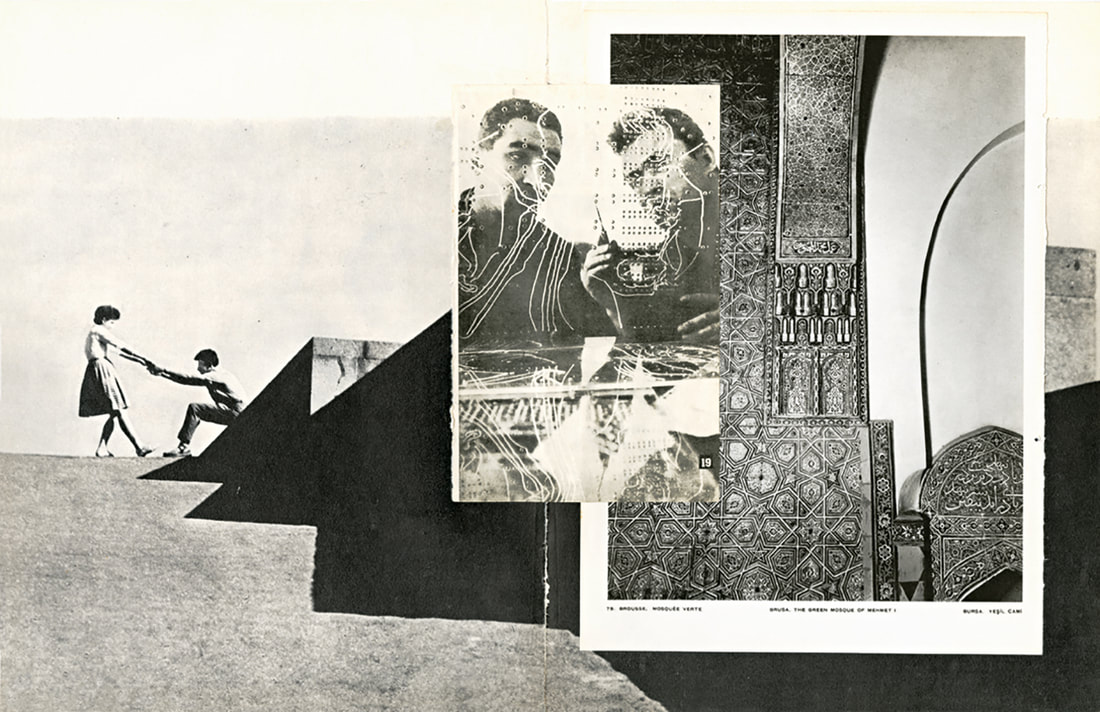

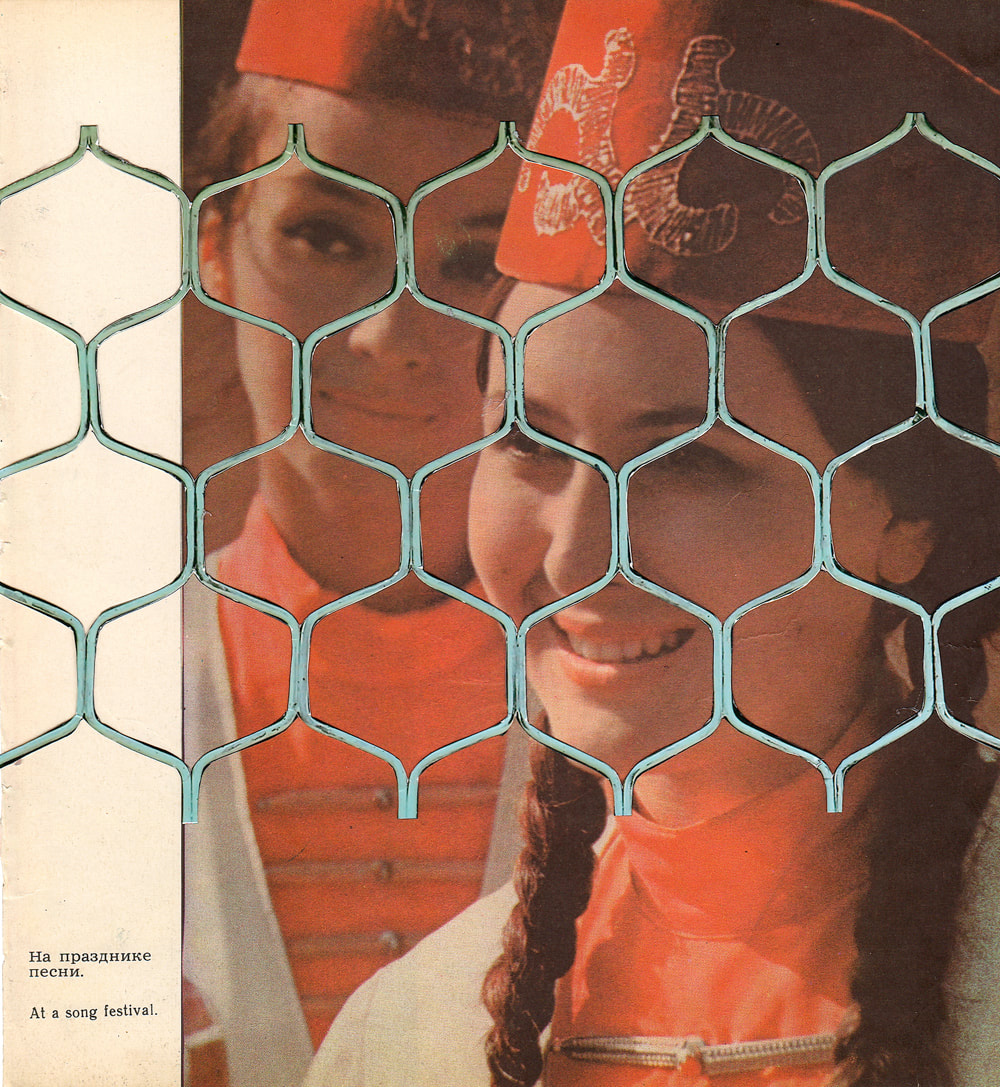

Aikaterini Gegisian: I rarely photograph, actually. For the first ten years since I graduated art school, I was a video artist or a filmmaker. I was making types of, what I call emotional structuralist films, films based on montage, interrogating how meaning is created between images and investigating the relationship between sound and text. These early video works explored the diasporic experience, as I come from a family of refugees, living in Greece, moving for studies in the UK, being in a position of movement, being between places. In 2011, a shift in my practice occurred. While conducted fieldwork in Armenia, I become fascinated by the post-Soviet landscape. In order to understand the changes in Armenian urban spaces, I started researching Soviet visual culture and documentary archives. I began collecting photographic albums that the Soviets produced, and this directed my practice towards found material. My first photographic work, which is the only work that I actually photographed, is Notes on a conception of a film from 2010. Over a period of five years and in ten different countries, I collected what you can call photographic snapshots. I created a diaristic installation, by writing on top of the photographs and by coloring them. After that, and in all other manifestations, my practice evolved as a collage practice engaged with found material. I may not have been conscious at the beginning that I was thinking as a photographer, but by now, it’s clear to me that this is a photographic practice.

Aikaterini Gegisian: I rarely photograph, actually. For the first ten years since I graduated art school, I was a video artist or a filmmaker. I was making types of, what I call emotional structuralist films, films based on montage, interrogating how meaning is created between images and investigating the relationship between sound and text. These early video works explored the diasporic experience, as I come from a family of refugees, living in Greece, moving for studies in the UK, being in a position of movement, being between places. In 2011, a shift in my practice occurred. While conducted fieldwork in Armenia, I become fascinated by the post-Soviet landscape. In order to understand the changes in Armenian urban spaces, I started researching Soviet visual culture and documentary archives. I began collecting photographic albums that the Soviets produced, and this directed my practice towards found material. My first photographic work, which is the only work that I actually photographed, is Notes on a conception of a film from 2010. Over a period of five years and in ten different countries, I collected what you can call photographic snapshots. I created a diaristic installation, by writing on top of the photographs and by coloring them. After that, and in all other manifestations, my practice evolved as a collage practice engaged with found material. I may not have been conscious at the beginning that I was thinking as a photographer, but by now, it’s clear to me that this is a photographic practice.

TiP: Why snapshots?

Gegisian: At that time, there was a general concern with the tourist imagination in my practice, probably because I was born in Greece, where being a tourist, or being a tourist destination, is a very dominant narrative. I suppose that is the reason why I approached tourist photography and explored how it produces certain types of identities, imaginations, and portraits of places. I wanted to understand how you inhabit a place and how you become part of the landscapes you encounter through the process of continuously taking snapshots as a tourist. I wanted to turn these fleeting encounters with places into experiences of permanence. I was also taking photographs because I'm interested in images. I'm an image maker that focuses on the technological images of photography and film. As an image maker then, I was exploring how tourist snapshots can become part of a personal memory and experience, a function that is lost in the process of excess accumulation. I wanted to disrupt that element.

TiP: How do you distinguish between a photograph and a film?

Gegisian: This is a good question, as I just finished my first feature length film that is constructed solely of archive material, titled Third Person (Plural). I don't think that the relation between film and photography is this idea that film contains photographic stills. I don't see the photograph as stills that then become animated. I don't make this type of connection in terms of the relation between photography and film. In general, what interests me is the different types of visual languages that photography and film have produced. I'm much more invested in the visual language of these technologies, in the histories of the media, and their role in writing history, rather than how the media relates to each other.

Gegisian: At that time, there was a general concern with the tourist imagination in my practice, probably because I was born in Greece, where being a tourist, or being a tourist destination, is a very dominant narrative. I suppose that is the reason why I approached tourist photography and explored how it produces certain types of identities, imaginations, and portraits of places. I wanted to understand how you inhabit a place and how you become part of the landscapes you encounter through the process of continuously taking snapshots as a tourist. I wanted to turn these fleeting encounters with places into experiences of permanence. I was also taking photographs because I'm interested in images. I'm an image maker that focuses on the technological images of photography and film. As an image maker then, I was exploring how tourist snapshots can become part of a personal memory and experience, a function that is lost in the process of excess accumulation. I wanted to disrupt that element.

TiP: How do you distinguish between a photograph and a film?

Gegisian: This is a good question, as I just finished my first feature length film that is constructed solely of archive material, titled Third Person (Plural). I don't think that the relation between film and photography is this idea that film contains photographic stills. I don't see the photograph as stills that then become animated. I don't make this type of connection in terms of the relation between photography and film. In general, what interests me is the different types of visual languages that photography and film have produced. I'm much more invested in the visual language of these technologies, in the histories of the media, and their role in writing history, rather than how the media relates to each other.

TiP: A photograph is always a moment. I agree with you that film isn't just a series of photographic stills, because what defines a photograph of the complete image, or at least as complete as it can be in our own mind, is that it's momentary. So aesthetically, it's just different. But also related.

Gegisian: I see the process of image making, not only as the action of taking a photograph or recording something, I see it also as the action of collaging different languages together, as a type of dialog that creates new images.

TiP: In what ways can photographs convey truth, or not?

Gegisian: I used to be interested in truth, because I was exploring how meaning is structured or created through film and photography. But for the last ten years I'm much more interested in the way photographs produce thought, that is in the visual language of the thought process, rather than in describing or chasing or dealing with truth. When I was making films, I was very much questioning the idea of the real. What is real? How can we represent it? Similarly, my first photographic work (Notes on a Conception of a Film) was very much concerned with how the tourist snapshots and the the emotional lives that I was connecting represent real moments. But as we enter a more and more social media constructed, hallucinatory reality, this idea of what is real became less interesting, or a much more layered experience than what you can just see. Images can become an expression of ideas and thoughts rather than just an evidentiary or indexical function.

Gegisian: I see the process of image making, not only as the action of taking a photograph or recording something, I see it also as the action of collaging different languages together, as a type of dialog that creates new images.

TiP: In what ways can photographs convey truth, or not?

Gegisian: I used to be interested in truth, because I was exploring how meaning is structured or created through film and photography. But for the last ten years I'm much more interested in the way photographs produce thought, that is in the visual language of the thought process, rather than in describing or chasing or dealing with truth. When I was making films, I was very much questioning the idea of the real. What is real? How can we represent it? Similarly, my first photographic work (Notes on a Conception of a Film) was very much concerned with how the tourist snapshots and the the emotional lives that I was connecting represent real moments. But as we enter a more and more social media constructed, hallucinatory reality, this idea of what is real became less interesting, or a much more layered experience than what you can just see. Images can become an expression of ideas and thoughts rather than just an evidentiary or indexical function.

TiP: How does the photographic image produce thought?

Gegisian: The answer to this relates specifically to my engagement with expanded collage processes, as the associating process of bringing together different material, different visual languages, different historical and temporal moments, and creating what I sometimes call an appropriate dialogue. The collaging of this heterogeneous and diverse material always preserves the original state of the sources. The relation to found material as documentary evidence is present, while at the same time new forms and images are being created. The thinking process, at least in how I practice photographic collage, is that the dialogues that I make happen allow you to both understand the historical, temporal, and geographic relations of the work, while at the same time allow for the emergence of new images and of new forms of imagination to emerge.

TiP: Could you talk about the work that's at the International Center of Photography?

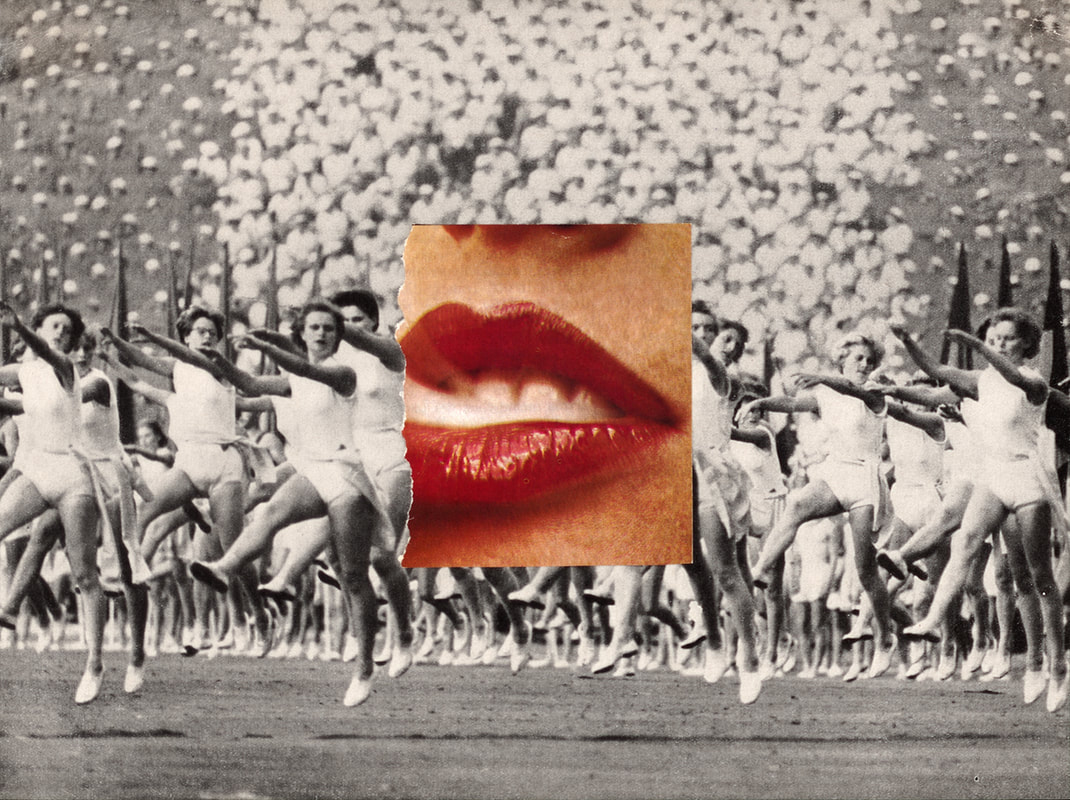

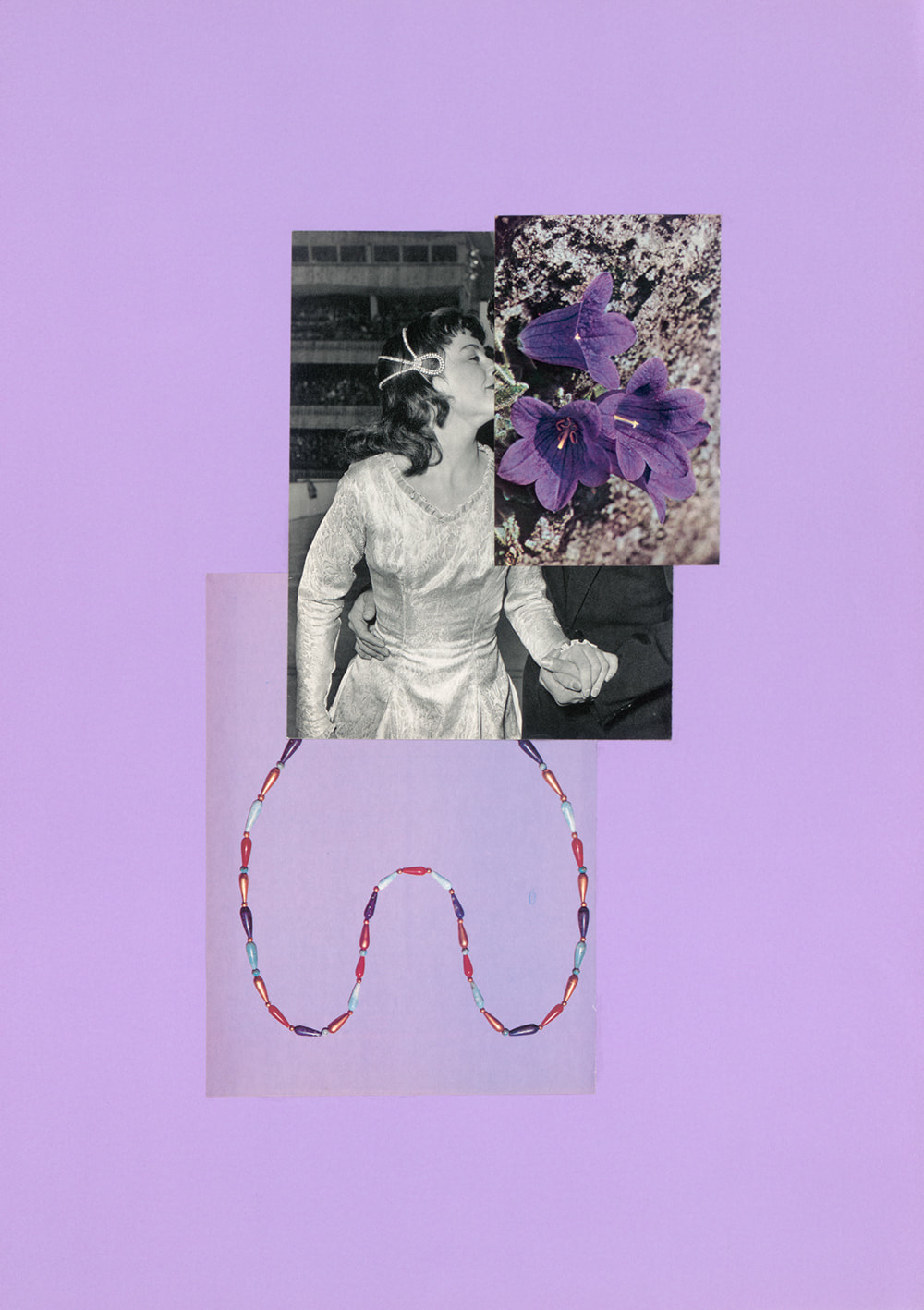

Gegisian: The work is called Handbook of the Spontaneous Other. The title is enigmatic or misleading or ambiguous because the viewer might expect an instructional manual. I am titling the work ‘handbook’ after all; it is supposed to give some type of instructions. The Handbook of the Spontaneous Other is both a collage project and a photo book. The collages are presented for the first time at the International Center of Photography and I'm curious to understand how they are perceived differently to the photo book. Handbook of the Spontaneous Other rethinks how the working body can express and feel pleasure without the burden of lifestyle and the drain that consumerist culture places on the body. It is the first work that I made where I moved away from looking at visual cultures of my heritage, Greek or Turkish or Armenian photographic albums, the visual cultural histories of the post-Soviet, post-Ottoman landscape, as I turned my attention to production of popular culture in the West. It is an exploration of how the body is portrayed within popular culture in the West. The Spontaneous Other is, for me, a figure that is trying to escape the othering processes that the patriarchal, masculine gaze has imposed on the body.

Gegisian: The answer to this relates specifically to my engagement with expanded collage processes, as the associating process of bringing together different material, different visual languages, different historical and temporal moments, and creating what I sometimes call an appropriate dialogue. The collaging of this heterogeneous and diverse material always preserves the original state of the sources. The relation to found material as documentary evidence is present, while at the same time new forms and images are being created. The thinking process, at least in how I practice photographic collage, is that the dialogues that I make happen allow you to both understand the historical, temporal, and geographic relations of the work, while at the same time allow for the emergence of new images and of new forms of imagination to emerge.

TiP: Could you talk about the work that's at the International Center of Photography?

Gegisian: The work is called Handbook of the Spontaneous Other. The title is enigmatic or misleading or ambiguous because the viewer might expect an instructional manual. I am titling the work ‘handbook’ after all; it is supposed to give some type of instructions. The Handbook of the Spontaneous Other is both a collage project and a photo book. The collages are presented for the first time at the International Center of Photography and I'm curious to understand how they are perceived differently to the photo book. Handbook of the Spontaneous Other rethinks how the working body can express and feel pleasure without the burden of lifestyle and the drain that consumerist culture places on the body. It is the first work that I made where I moved away from looking at visual cultures of my heritage, Greek or Turkish or Armenian photographic albums, the visual cultural histories of the post-Soviet, post-Ottoman landscape, as I turned my attention to production of popular culture in the West. It is an exploration of how the body is portrayed within popular culture in the West. The Spontaneous Other is, for me, a figure that is trying to escape the othering processes that the patriarchal, masculine gaze has imposed on the body.

TiP: Talk about that, because I think the masculine gaze has been a plague upon our understanding of the history of photography.

Gegisian: I think the masculine gaze is not only a plague on our understanding of photography, but in how knowledge is constructed in general. In terms of photography, although I am interested in popular culture, I didn't address the masculine gaze until I started making the Handbook of the Spontaneous Other, because up until then I was questioning how national identities are constructed in the post-Soviet and post-Ottoman spaces. The patriarchal masculine gaze was obstructed within the larger oppressive systems, larger political ideological systems. In looking at the popular culture of the West, which is what the Handbook of the Spontaneous Other reflects on, I realize that most of the images are produced by men. It is really as simple as that. If you're working with images produced in the fifties and sixties and seventies, those images are much more likely to have been produced by men. But when we look back at these images, we are not consciously thinking “these images were produced by men.” Handbook of the Spontaneous Other uses this type of grammar of popular culture, while acknowledging that with feminist avant-garde photographic practices the female body became exuberant, but also making visible a larger cultural environment where the male gaze was still dominant.

TiP: How do you think the feminine gaze becomes visible in image making?

Gegisian: This is a good question because sometimes I describe my work as a feminist rereading of visual history. I go back to found images not because I am nostalgic for the visual culture of the sixties for example. I go back because I want to reread these image histories and make visible different sets of relations. It's important to continuously create new sets of relations and dialogs. And at some point, I thought of the term female gaze or the feminist gaze, but I found it problematic because the gaze is based on the notion of the singular eye that surveils the world. I'm not sure if it's valuable to attempt to create the female gaze as an opposition to the male singular gaze. Maybe it’s interesting to find a different way of describing the thinking - looking processes and voices of women, than assigning them the power of a gaze.

Gegisian: I think the masculine gaze is not only a plague on our understanding of photography, but in how knowledge is constructed in general. In terms of photography, although I am interested in popular culture, I didn't address the masculine gaze until I started making the Handbook of the Spontaneous Other, because up until then I was questioning how national identities are constructed in the post-Soviet and post-Ottoman spaces. The patriarchal masculine gaze was obstructed within the larger oppressive systems, larger political ideological systems. In looking at the popular culture of the West, which is what the Handbook of the Spontaneous Other reflects on, I realize that most of the images are produced by men. It is really as simple as that. If you're working with images produced in the fifties and sixties and seventies, those images are much more likely to have been produced by men. But when we look back at these images, we are not consciously thinking “these images were produced by men.” Handbook of the Spontaneous Other uses this type of grammar of popular culture, while acknowledging that with feminist avant-garde photographic practices the female body became exuberant, but also making visible a larger cultural environment where the male gaze was still dominant.

TiP: How do you think the feminine gaze becomes visible in image making?

Gegisian: This is a good question because sometimes I describe my work as a feminist rereading of visual history. I go back to found images not because I am nostalgic for the visual culture of the sixties for example. I go back because I want to reread these image histories and make visible different sets of relations. It's important to continuously create new sets of relations and dialogs. And at some point, I thought of the term female gaze or the feminist gaze, but I found it problematic because the gaze is based on the notion of the singular eye that surveils the world. I'm not sure if it's valuable to attempt to create the female gaze as an opposition to the male singular gaze. Maybe it’s interesting to find a different way of describing the thinking - looking processes and voices of women, than assigning them the power of a gaze.

TiP: Maybe the idea of the gaze is wrong to begin with.

Gegisian: Exactly, the gaze is this singular eye that surveils, and because it observes, it has knowledge, and can create the truth or interpret reality. For the moment, I'm invested in the process of re-reading image histories of the past through the new types of dialogs established in my expanded collage practice. I do still find it important to talk from the position of being a woman, but I'm currently thinking “How else can we describe this type of visual production?”

TiP: What are the characteristics, then, of feminist photographic production?

Gegisian: Handbook of the Spontaneous Other definitely makes visible an exuberant female body that is happy to be seen. Historically, feminist art practices have been reclaiming the modes of representation in photography and film. In such practices of the sixties and seventies, you begin to sense a female body that becomes exuberant, that can dance and move. Specifically, in my collage photographic practice, the feminist position is expressed as the reclaiming of the visual histories of the masculine gaze and rethinking and reimagining them by allowing different set of relations to become visible. If you look through the Handbook, you see that there are male and female bodies coming together, intermingled with animals, with nature, with clams, with forests, with trees. I'm interested in formulating a feminist position that goes beyond binaries and is able to acknowledge a set of relations between different identities or positions.

Gegisian: Exactly, the gaze is this singular eye that surveils, and because it observes, it has knowledge, and can create the truth or interpret reality. For the moment, I'm invested in the process of re-reading image histories of the past through the new types of dialogs established in my expanded collage practice. I do still find it important to talk from the position of being a woman, but I'm currently thinking “How else can we describe this type of visual production?”

TiP: What are the characteristics, then, of feminist photographic production?

Gegisian: Handbook of the Spontaneous Other definitely makes visible an exuberant female body that is happy to be seen. Historically, feminist art practices have been reclaiming the modes of representation in photography and film. In such practices of the sixties and seventies, you begin to sense a female body that becomes exuberant, that can dance and move. Specifically, in my collage photographic practice, the feminist position is expressed as the reclaiming of the visual histories of the masculine gaze and rethinking and reimagining them by allowing different set of relations to become visible. If you look through the Handbook, you see that there are male and female bodies coming together, intermingled with animals, with nature, with clams, with forests, with trees. I'm interested in formulating a feminist position that goes beyond binaries and is able to acknowledge a set of relations between different identities or positions.

TiP: How would you finish the sentence, “Photography produces thought by…?”

Gegisian: Photography produces thought through the continuous creation of images, images creating images, creating images, in a continuous circle of production. This way of thinking is the crystallization of 15 years of expanded photographic collage practice, of rethinking the notion of photography as a scientific technological apparatus that captures a moment in time, while reclaiming it and placing it in the contemporary moment of continuous interaction with images in all aspects of our lives. Photography becomes a process for the continuous creation of images.

Gegisian: Photography produces thought through the continuous creation of images, images creating images, creating images, in a continuous circle of production. This way of thinking is the crystallization of 15 years of expanded photographic collage practice, of rethinking the notion of photography as a scientific technological apparatus that captures a moment in time, while reclaiming it and placing it in the contemporary moment of continuous interaction with images in all aspects of our lives. Photography becomes a process for the continuous creation of images.

|

|

Delve deeper |