This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

About the PhotographersLindokuhle Sobekwa is a South African Magnum photographer born in Katlehong, Johannesburg in 1995. Sobekwa came to photography in 2012 through his participation in the Of Soul and Joy Project, an educational program. Sobekwa’s early projects dealt with poverty and unemployment in the townships of South Africa, as well as the growing nyaope drug crisis within them. His ongoing works, as well as revisiting those early themes, also deal with his own life – for example his relationship with his sister, Ziyanda, who died after becoming estranged from her family.

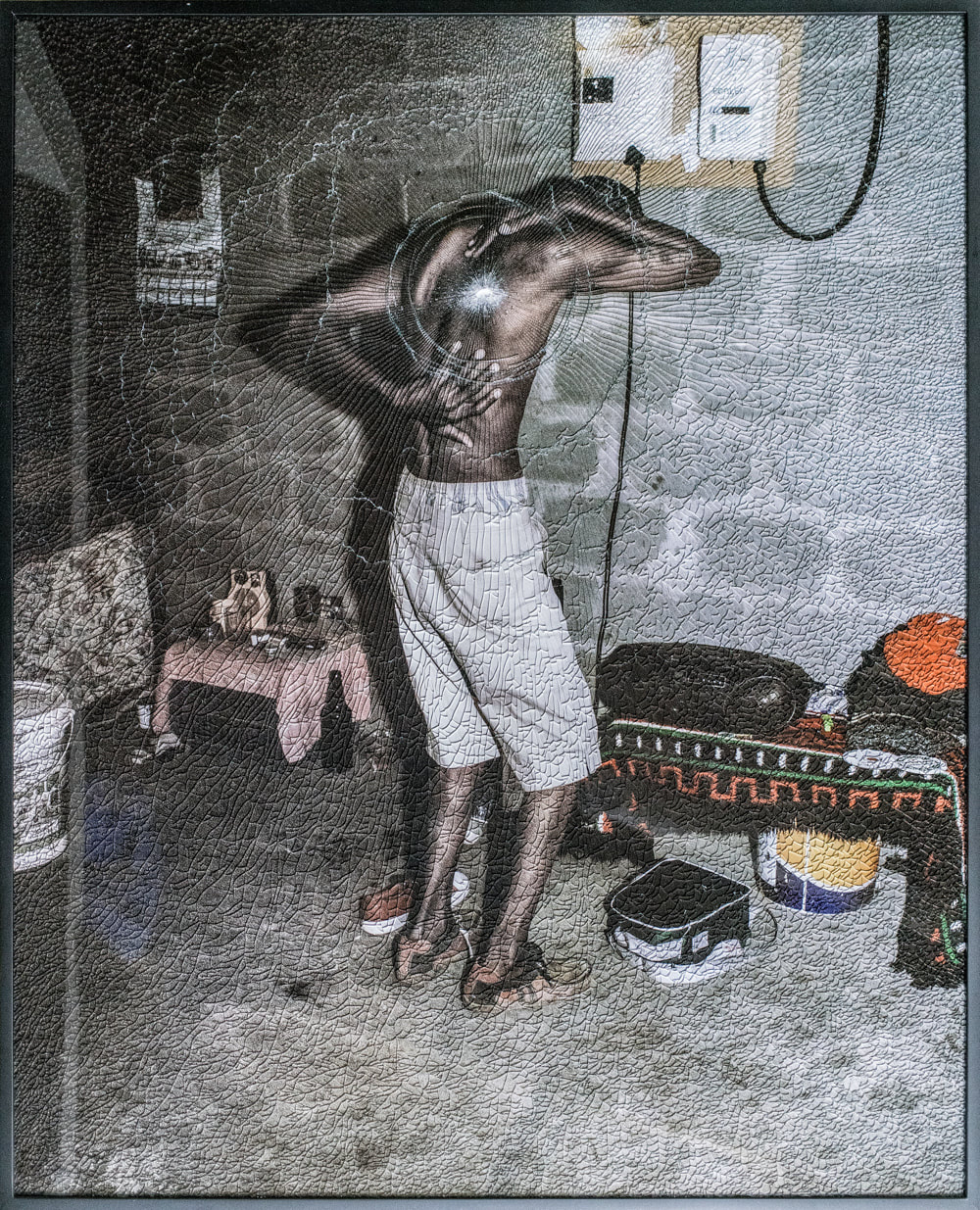

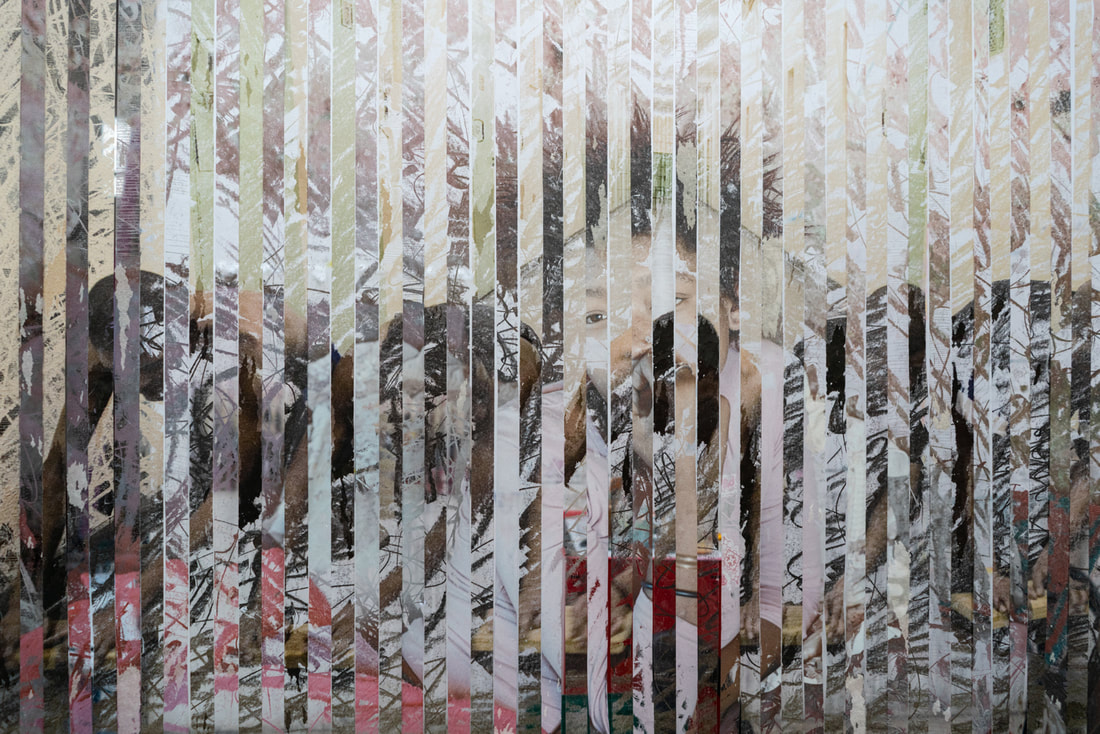

Mikhael Subotzky (b. 1981, Cape Town) is a Johannesburg based artist whose works in multiple mediums engage critically with the instability of images and the politics of representation. Subotzky studied at Michaelis School of Fine Art in Cape Town and his first body of photographic work, Die Vier Hoeke (The Four Corners), was an in-depth study of the South African penal system. Umjiegwana (The Outside) and Beaufort West extended this investigation to the relationship between everyday life in post-apartheid South Africa and the historical, spatial and institutional structures of control. Subotzky joined Magnum Photos in 2007. His practice has evolved to include film installation, video, photography, collage and painting.

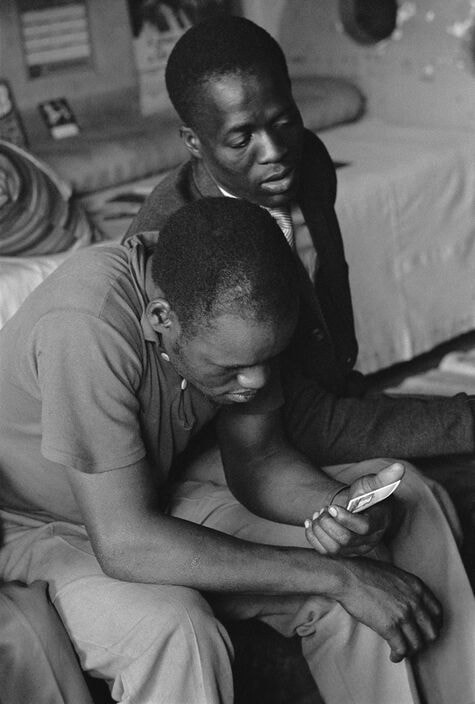

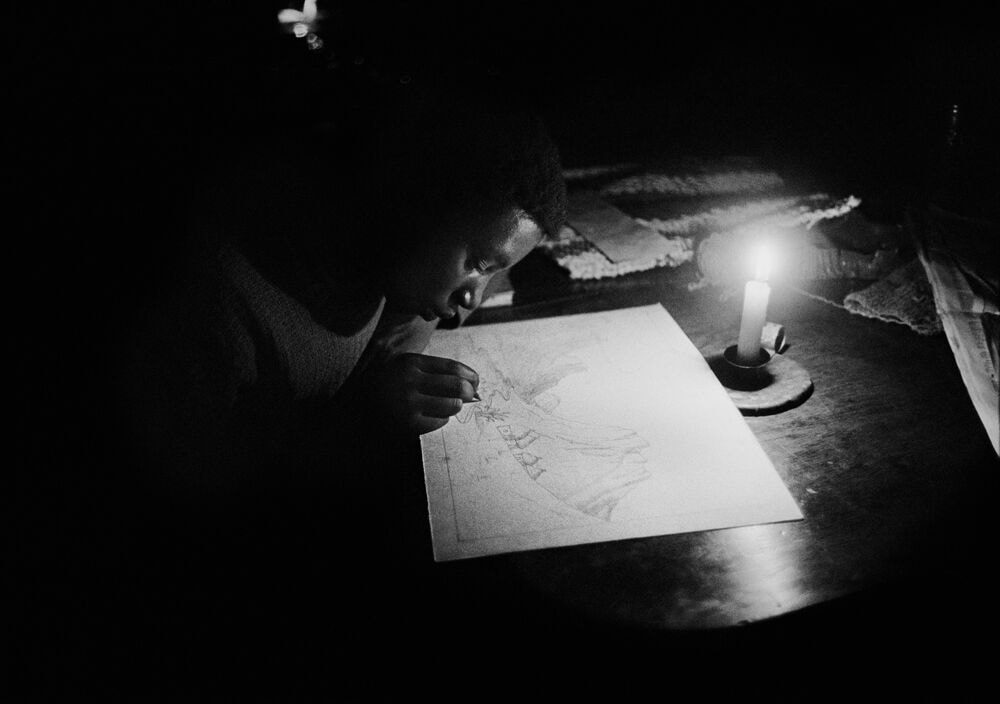

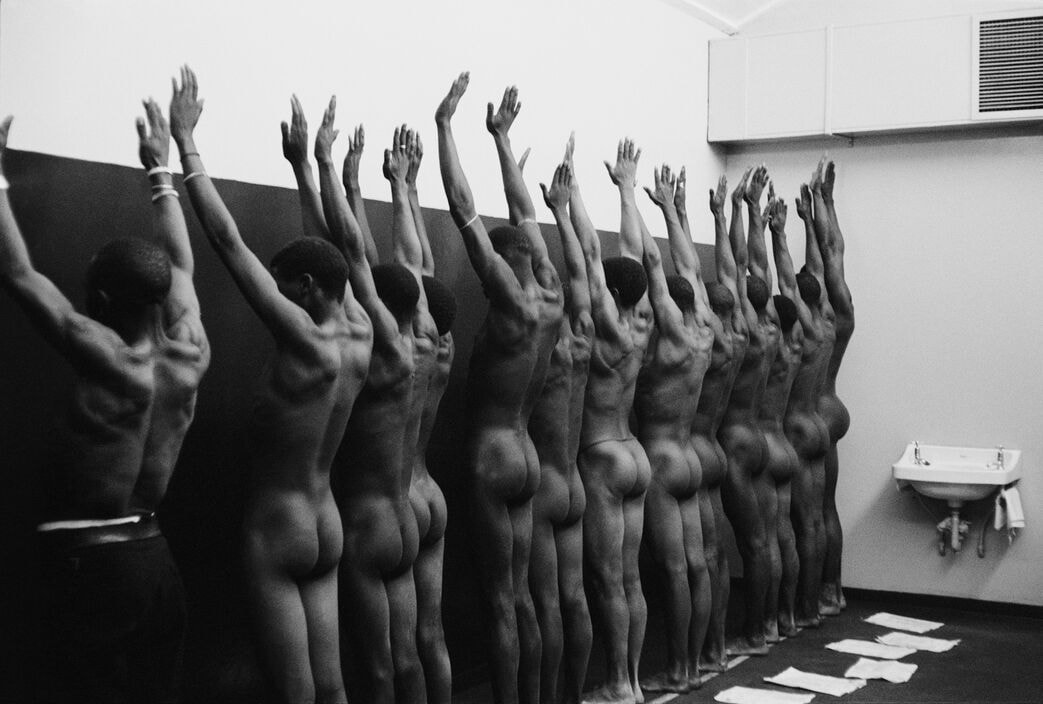

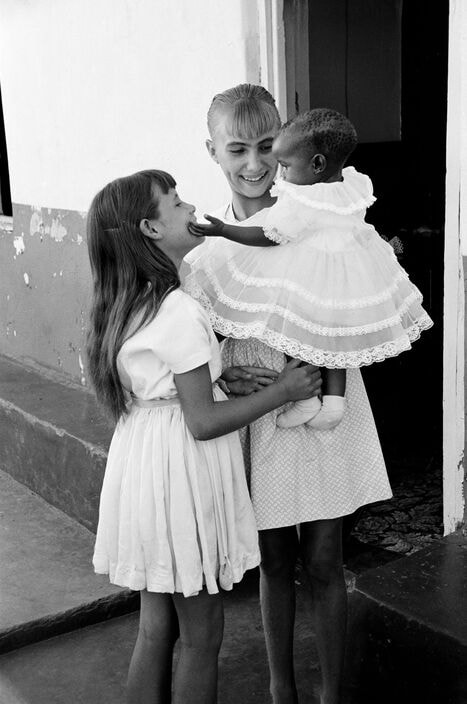

Ernest Cole was born in South Africa’s Transvaal in 1940 and died in New York City in 1990. During his life he was known for only one book: House of Bondage – published in 1967. In 2011, the Hasselblad Foundation produced a follow-up: Ernest Cole: Photographer. Cole’s early work chronicled the horrors of apartheid and in 1966 he fled the Republic of South Africa becoming a ‘banned person.’ In North America, he concentrated on street photography in primarily urban settings. Between 1969 and 1971, Cole spent an extensive amount of time on regular visits to Sweden where he became involved with the Tiofoto collective and exhibited his work. From 1972, Cole’s life fell into disarray and he ceased to work as a photographer, losing control of his archive and negatives in the process. Having experienced periods of homelessness, Cole died aged forty-nine of pancreatic cancer in 1990. In 2017, more than 60,000 of Cole’s negatives missing for more than forty years were discovered in a Stockholm bank vault. This work is now being examined and catalogued. |

|

Truth in Photography: Talk a little bit about the idea of truth in photography from your point of view.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa: The idea of truth in photography, it's really interesting. I’m thinking of something that I read, I don't remember where, but it speaks about this idea of “seeing is believing.” And for a very long time, people have believed in what the photographers were depicting. But it was only later once I became a photographer when I realized that photography itself creates its own truth, or I create my own truth - which is what I was looking at at that particular time. That truth exists amongst other truths as well, or other realities that are happening at the same time. The idea of truth is very fragmented. When you think of the truth in an event, even if it is not documented, everyone has their vision of the story. I look at photography as my vision of the story as what I decided to frame. Maybe Mikhael, or anyone, when they look at that same event, would see it differently. I still believe that photographers have something very interesting to say about this idea of reality or the truth.

Mikhael Subotzky: I want to take the word and the idea back from the far right, who completely distort any notion of not just truth, but our sense of reality. I'm very much for the kind of societal pushback against this tendency. At the same time, I'm going to be very honest, I don't like associating the word truth with photography. I think photography suffers from the burden of its indexical relationship to the world. Visual perception is mediated, whether that's between the eye and the brain, or the lens and the sensor, the focal length of the lens, the fact that a camera points in one direction rather than the other, the fact that the camera's held by Lindokuhle or myself, what we find interesting, which images are playing in our heads while we're making those photographs. I don't believe that photography and truth can be the same thing. But I do believe that photographers can have important things to say about the reality around us. That comes from acknowledging this subjectivity and acknowledging their intentions in the photographs that are presented. I don't believe in absolute notions of truth. I'm very much a card-carrying post-structuralist, and I think it's almost tragic the way that some of the ideas of post-structuralism have been distorted by post-truth Trumpism. So when Deleuze invokes the concept of difference, not identity, he's really saying (to paraphrase in criminally simple terms) that absolutes don't exist, and we find meaning in relation to other humans and in relation to sets of ideas. It's really important for me that photography acknowledges all those complexities and tries to be honest, but without subscribing to big ideas like truth.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa: The idea of truth in photography, it's really interesting. I’m thinking of something that I read, I don't remember where, but it speaks about this idea of “seeing is believing.” And for a very long time, people have believed in what the photographers were depicting. But it was only later once I became a photographer when I realized that photography itself creates its own truth, or I create my own truth - which is what I was looking at at that particular time. That truth exists amongst other truths as well, or other realities that are happening at the same time. The idea of truth is very fragmented. When you think of the truth in an event, even if it is not documented, everyone has their vision of the story. I look at photography as my vision of the story as what I decided to frame. Maybe Mikhael, or anyone, when they look at that same event, would see it differently. I still believe that photographers have something very interesting to say about this idea of reality or the truth.

Mikhael Subotzky: I want to take the word and the idea back from the far right, who completely distort any notion of not just truth, but our sense of reality. I'm very much for the kind of societal pushback against this tendency. At the same time, I'm going to be very honest, I don't like associating the word truth with photography. I think photography suffers from the burden of its indexical relationship to the world. Visual perception is mediated, whether that's between the eye and the brain, or the lens and the sensor, the focal length of the lens, the fact that a camera points in one direction rather than the other, the fact that the camera's held by Lindokuhle or myself, what we find interesting, which images are playing in our heads while we're making those photographs. I don't believe that photography and truth can be the same thing. But I do believe that photographers can have important things to say about the reality around us. That comes from acknowledging this subjectivity and acknowledging their intentions in the photographs that are presented. I don't believe in absolute notions of truth. I'm very much a card-carrying post-structuralist, and I think it's almost tragic the way that some of the ideas of post-structuralism have been distorted by post-truth Trumpism. So when Deleuze invokes the concept of difference, not identity, he's really saying (to paraphrase in criminally simple terms) that absolutes don't exist, and we find meaning in relation to other humans and in relation to sets of ideas. It's really important for me that photography acknowledges all those complexities and tries to be honest, but without subscribing to big ideas like truth.

TiP: Your work is parallel, but you have different approaches. Talk about your own work and where you're going with it.

Sobekwa: My work is connected, but different. I respond to what concerns or interests me. Early projects dealt with societal issues in the townships of South Africa, as well as the growing nyaope drug crisis within them, which then informed my more personal work like Daleside: Static Dreams, a book that I worked on with my collaborator Cyprien Clément-Delma. Daleside developed from curiosity about this place that I grew up knowing through my mother who was employed there as a sleep-in domestic worker in the early 2000s in what was a predominately white town. When we started making work there a lot had changed. Daleside had similar social challenges that were not different from my community.

I then moved on to a more personal project, I carry her photo with Me, which is about my sister's disappearance and other complexities of this country. The project started when I discovered a family group portrait where my sister's face is cut out so that they could use it for her funeral. I used a scrapbook aesthetic with handwritten notes as a means for me to engage both with the memory of my sister and the wider implications of such disappearances—a troubling part of South Africa’s history.

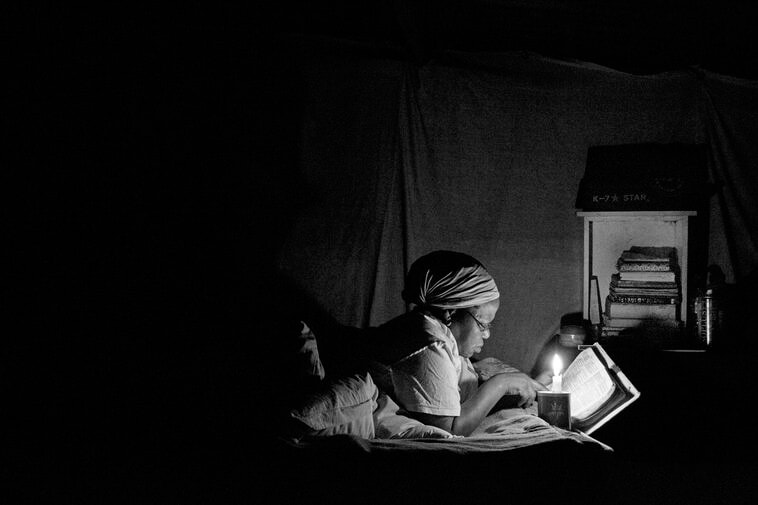

The lockdown project started during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic when the world was faced with fear and came to a standstill. We were all experiencing a universal panic. I photographed my experiences in the suburbs where I quarantined at a friend’s place. Back at home in the township, people had to social distance in small shacks. The experience of COVID-19 in South Africa exposed the inequality that already existed there. There was more policing in the township than in the suburbs, and many people from the township had lost their jobs and were faced with many social issues such electricity crises and services delivery that lead into nation-wide unrest in the subsequent months, including the looting of shops and xenophobic attacks against foreign nationals. I photographed some of my family's intimate moments, trying to capture some kind of normality in this era of masking and social distancing we found ourselves in.

TiP: How do you document community? How do you get a sense of the social dynamics without posing people into groups or just watching the way people work?

Sobekwa: It all starts with one person you develop a relationship and trust with, and then it spreads out to different people and places within the community. It's a natural response. In the process I try to collaborate to learn more about the community. South Africa is a very racialized country against the backdrop of inequality. It already exists within categories that were imposed on people.

TiP: To what extent when you're making photographs like this do you interact with the subject? What is your way of working?

Sobekwa: I spend a lot of time developing this kind of trust in people I photograph, and a lot of time it doesn't always go my way. It's a working process. I always return photographs I make and learn a lot about how they would like to be seen, and we find a common ground to collaborate. My working process always evolves. It adapts to where I happen to be working. For instance, in Daleside we spent 5 years doing work there and there were a set of challenges I faced that I had to adapt to and find a mode of working. Challenges such as being racially marked, my camera had to be visible so that I was not mistaken for a criminal or someone looking for work, and people remembered me when I had my camera.

Subotzky: I can’t tell you how much I wish our forefather, Ernest Cole, was here to have this conversation with us. I think he would have such a wise take on it. I think he was so aware of exactly these issues, working as a 27-year-old in 1960s South Africa, as a black man who had to wear masks to really make the work that he did. I'm thinking of the image of the mineworkers in the showers. We know from his accounts that in order to make this photograph, Cole describes how he hid his camera in a bag under sandwiches in order to get it into the mine compound. He's lying in order to tell the truth, which again for me speaks so strongly to how complex and contradictory these ideas are. I also was just looking at something he said in a letter that he wrote in 1968 to Sweden, explaining his situation as a stateless person living in New York for the past 26 months as he was applying for a visa.

Sobekwa: My work is connected, but different. I respond to what concerns or interests me. Early projects dealt with societal issues in the townships of South Africa, as well as the growing nyaope drug crisis within them, which then informed my more personal work like Daleside: Static Dreams, a book that I worked on with my collaborator Cyprien Clément-Delma. Daleside developed from curiosity about this place that I grew up knowing through my mother who was employed there as a sleep-in domestic worker in the early 2000s in what was a predominately white town. When we started making work there a lot had changed. Daleside had similar social challenges that were not different from my community.

I then moved on to a more personal project, I carry her photo with Me, which is about my sister's disappearance and other complexities of this country. The project started when I discovered a family group portrait where my sister's face is cut out so that they could use it for her funeral. I used a scrapbook aesthetic with handwritten notes as a means for me to engage both with the memory of my sister and the wider implications of such disappearances—a troubling part of South Africa’s history.

The lockdown project started during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic when the world was faced with fear and came to a standstill. We were all experiencing a universal panic. I photographed my experiences in the suburbs where I quarantined at a friend’s place. Back at home in the township, people had to social distance in small shacks. The experience of COVID-19 in South Africa exposed the inequality that already existed there. There was more policing in the township than in the suburbs, and many people from the township had lost their jobs and were faced with many social issues such electricity crises and services delivery that lead into nation-wide unrest in the subsequent months, including the looting of shops and xenophobic attacks against foreign nationals. I photographed some of my family's intimate moments, trying to capture some kind of normality in this era of masking and social distancing we found ourselves in.

TiP: How do you document community? How do you get a sense of the social dynamics without posing people into groups or just watching the way people work?

Sobekwa: It all starts with one person you develop a relationship and trust with, and then it spreads out to different people and places within the community. It's a natural response. In the process I try to collaborate to learn more about the community. South Africa is a very racialized country against the backdrop of inequality. It already exists within categories that were imposed on people.

TiP: To what extent when you're making photographs like this do you interact with the subject? What is your way of working?

Sobekwa: I spend a lot of time developing this kind of trust in people I photograph, and a lot of time it doesn't always go my way. It's a working process. I always return photographs I make and learn a lot about how they would like to be seen, and we find a common ground to collaborate. My working process always evolves. It adapts to where I happen to be working. For instance, in Daleside we spent 5 years doing work there and there were a set of challenges I faced that I had to adapt to and find a mode of working. Challenges such as being racially marked, my camera had to be visible so that I was not mistaken for a criminal or someone looking for work, and people remembered me when I had my camera.

Subotzky: I can’t tell you how much I wish our forefather, Ernest Cole, was here to have this conversation with us. I think he would have such a wise take on it. I think he was so aware of exactly these issues, working as a 27-year-old in 1960s South Africa, as a black man who had to wear masks to really make the work that he did. I'm thinking of the image of the mineworkers in the showers. We know from his accounts that in order to make this photograph, Cole describes how he hid his camera in a bag under sandwiches in order to get it into the mine compound. He's lying in order to tell the truth, which again for me speaks so strongly to how complex and contradictory these ideas are. I also was just looking at something he said in a letter that he wrote in 1968 to Sweden, explaining his situation as a stateless person living in New York for the past 26 months as he was applying for a visa.

|

Without wishing to be negative about life in this country, it is quite evident to me that it will be difficult for me to work here at this particular period of my life. In my observation of the Black man's life in South Africa as presented in House of Bondage, my personal attitude was committed to exposing the evils of South Africa. When I left home I thought I would focus my talents on other aspects of life, which I assumed would be more hopeful, and some joy to it. However, what I have seen in this country over the past two years has proved me wrong. Recording the truth at whatever cost is one thing but finding one having to live a lifetime of being a chronicler of misery and injustice and callousness is another. And such matter is about the only assignments magazines here want to offer me because the subject matter of my first book happened to be centred on a "race" issue, the color of my skin - another incidental matter - and the fact that I endured and escaped the living hell that is South Africa. The total man does not live one experience. He is moulded and shaped by the diversity of other experiences into some form of the whole man. I will most probably return to the U.S. in the future to complete the cycle of study of my observations made here over the past two years. But right now my earnest desire is to have a breath of fresh air. ~Ernest Cole |

There's an acknowledgment of how remarkably aware he was for such a young man that he was doing propaganda with House of Bondage, that he was telling a particular story in order to try and change things in South Africa. And again, that doesn't for me deflect from the “truth” of what he depicted. Again, I think his work is incredibly important both to myself and even maybe more so to Lindokuhle. I'd just like to mention this comment that Lindo and myself both really hold dear, which is in the forward to the new Aperture edition of the House of Bondage, which was written by our poet laureate in South Africa, Mongane Wally Serote, and he titles that forward “Lament.” And he's really lamenting the fact that Cole sacrificed so much to make that work, yet so much of South Africa looks and feels the same and is similarly experienced by black South Africans to the South Africa of the 1960s. I think that's really an important aspect of Lindokuhle’s work, because Lindo’s work has many different nuances to it. And one of those nuances is the sense that some of the photographs that Lindo has taken of conditions in South Africa during the lockdown in the townships where he grew up looked very, very similar to the photographs that Cole took in the 1960s.

TiP: This whole issue of home is one that concerns me a great deal. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Sobekwa: The idea of home here has been fragmented over the years by colonization that disfranchised black people of their land, identity, and culture. The body of work that I am working on, Ezilalini (The Country), is my way of going to my ancestral home. Even though I was born in Johannesburg and spent all my life here and have regarded this place as home, I am often asked the question, “Where are you from?” and when you respond and say, “I am from Johannesburg,” people ask you, “Where is your real home?”

Johannesburg has long been regarded as a place of work. Since the discovery of gold in the 1800s many black migrants left their families back in their homelands to provide cheap labor in the gold mines. This form of violence that humiliated black bodies was documented by Ernest Cole in House of Bondage. Many black households were left without a father figure, and that disrupted the family structure.

Sobekwa: The idea of home here has been fragmented over the years by colonization that disfranchised black people of their land, identity, and culture. The body of work that I am working on, Ezilalini (The Country), is my way of going to my ancestral home. Even though I was born in Johannesburg and spent all my life here and have regarded this place as home, I am often asked the question, “Where are you from?” and when you respond and say, “I am from Johannesburg,” people ask you, “Where is your real home?”

Johannesburg has long been regarded as a place of work. Since the discovery of gold in the 1800s many black migrants left their families back in their homelands to provide cheap labor in the gold mines. This form of violence that humiliated black bodies was documented by Ernest Cole in House of Bondage. Many black households were left without a father figure, and that disrupted the family structure.

Subotzky: I wanted to link what Lindo was saying to my own work and then back to your starting point around truth. I relate to what Cole was saying about the expectation to make a certain type of work based on his first body of work. I also did a first body of work in prisons, which set a particular kind of documentary gaze. That was important to me at the time, but wasn't the work that I wanted to be doing for the rest of my life. I live in a country where a vast majority of people are black or what we call “colored.” I'm in a very small but very privileged and economically powerful white minority. So at a certain point, it became very important for me to start looking at that kind of perspective and what that privilege and economic power means and to look at the construction of whiteness. And that goes far beyond this image, but it was taken in one of the wealthy, mainly white suburbs in Johannesburg. And I was just so surprised by a scene where there was a street party, reclaiming public space in order to not just live behind our high walls and our barbed wire. The irony is kind of dripping off every aspect of the scene. I love telling this story, because when I arrived on the scene, the security guard was sitting very close to where he is sitting in the photograph. But like Lindo, I always make my presence known and ask for permission to take a photograph, which I did for both the security guard and the family enjoying the street party. And they both said, yes, I could take the photograph. But then when they saw that I was including the security guard, they got embarrassed and they called him over and said, “No, bring your chair here and set up the table.” They wanted it to look like he was part of the party and that they included him in the food and the drink and everything. And then I was like, I can’t photograph this because that's not the scene that I saw. I asked him to move back to where he was. I had to kind of construct it to be more like how it was when I arrived. Then there's another layer in that the photograph was exhibited in South Africa, and one of the people in the photograph wrote to the newspaper saying that I'd constructed it and I'd done it to make them look bad. There are all these layers to the way the truth of that moment was contested.

TiP: Within the world of photography, who has the right to tell the story, from your point of view, and how do you address that in your work?

Sobekwa: There's always something interesting one can get from the insider and an outsider perspective. But what is very important is the regard for the people you photograph. I’ve been in both. When you’re the insider it’s important to create a safe distance to see with clarity, and when you’re an outside it’s important to be closer to bridge the gap of othering.

Subotzky: I 100% agree with that. And I think Lindo's own words in the Daleside book speak very powerfully to that. With photography, there is this paradox where sometimes it helps to be an insider, sometimes it helps to be an outsider. It becomes less about who has the right to say what and more about your sensitivity. That sensitivity will speak, whether you’re an insider or an outsider. I do think that the identity politics that have taken over in American academia stifles a kind of honest being in the world. Like in my case, it would be dishonest if one were to take what you said to the extreme and say, white people only have a right to photograph white people. It would be dishonest for me to photograph only white people in South Africa, a country where 10% of the population is white. All those absolutes, whether they come from the right or the left, are so stifling, and they're amplified by social media and the way we talk to each other in this world. I really believe in the power of art, and photography in particular, for more nuanced readings of the world. You look at Lindo's photographs in South Africa and you learn a hundred times more than you will in some debate on social media, or in traditional media even. That's why I still engage in photography and with art, because I believe that's really important.

Sobekwa: There's always something interesting one can get from the insider and an outsider perspective. But what is very important is the regard for the people you photograph. I’ve been in both. When you’re the insider it’s important to create a safe distance to see with clarity, and when you’re an outside it’s important to be closer to bridge the gap of othering.

Subotzky: I 100% agree with that. And I think Lindo's own words in the Daleside book speak very powerfully to that. With photography, there is this paradox where sometimes it helps to be an insider, sometimes it helps to be an outsider. It becomes less about who has the right to say what and more about your sensitivity. That sensitivity will speak, whether you’re an insider or an outsider. I do think that the identity politics that have taken over in American academia stifles a kind of honest being in the world. Like in my case, it would be dishonest if one were to take what you said to the extreme and say, white people only have a right to photograph white people. It would be dishonest for me to photograph only white people in South Africa, a country where 10% of the population is white. All those absolutes, whether they come from the right or the left, are so stifling, and they're amplified by social media and the way we talk to each other in this world. I really believe in the power of art, and photography in particular, for more nuanced readings of the world. You look at Lindo's photographs in South Africa and you learn a hundred times more than you will in some debate on social media, or in traditional media even. That's why I still engage in photography and with art, because I believe that's really important.