This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

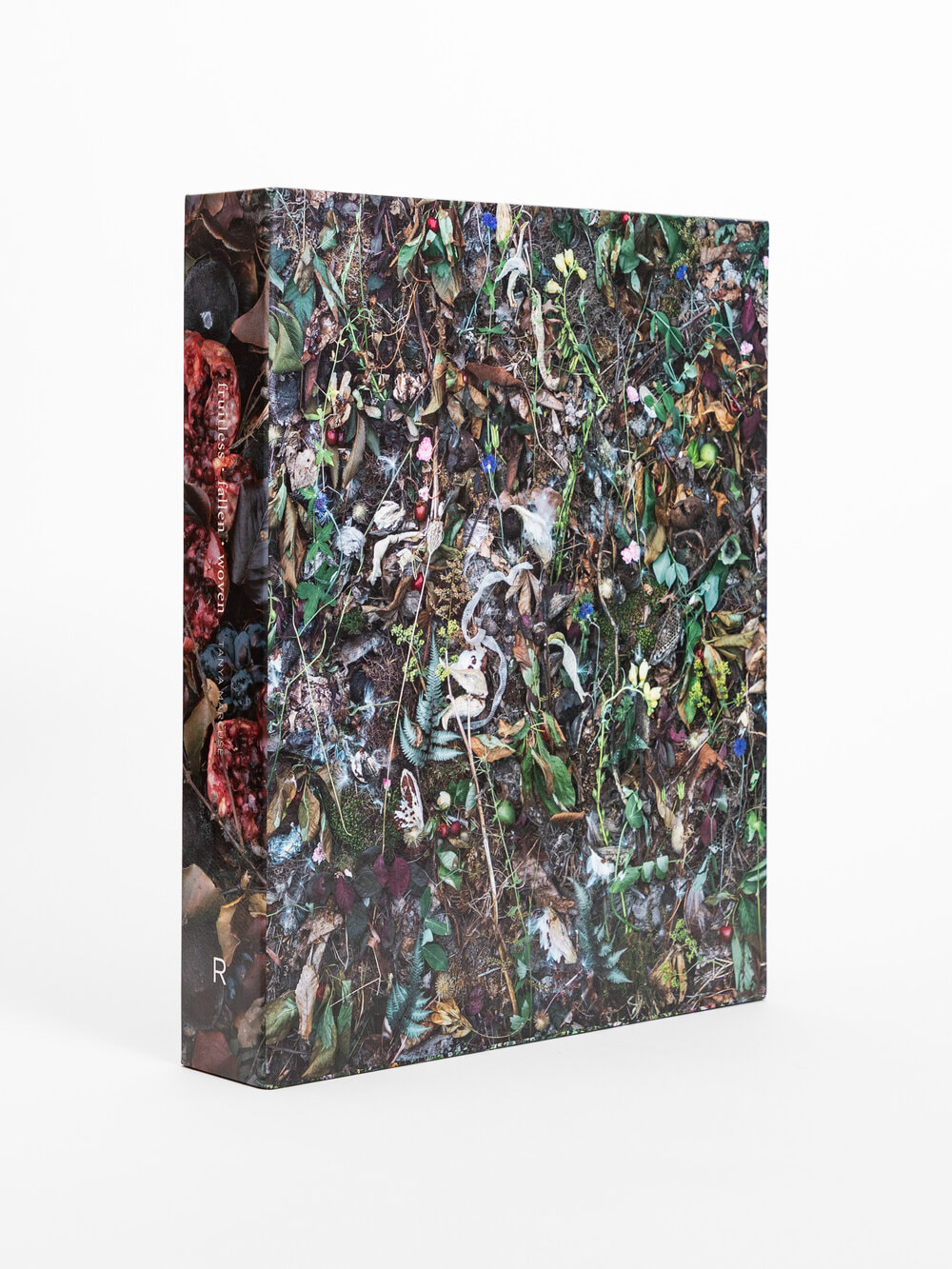

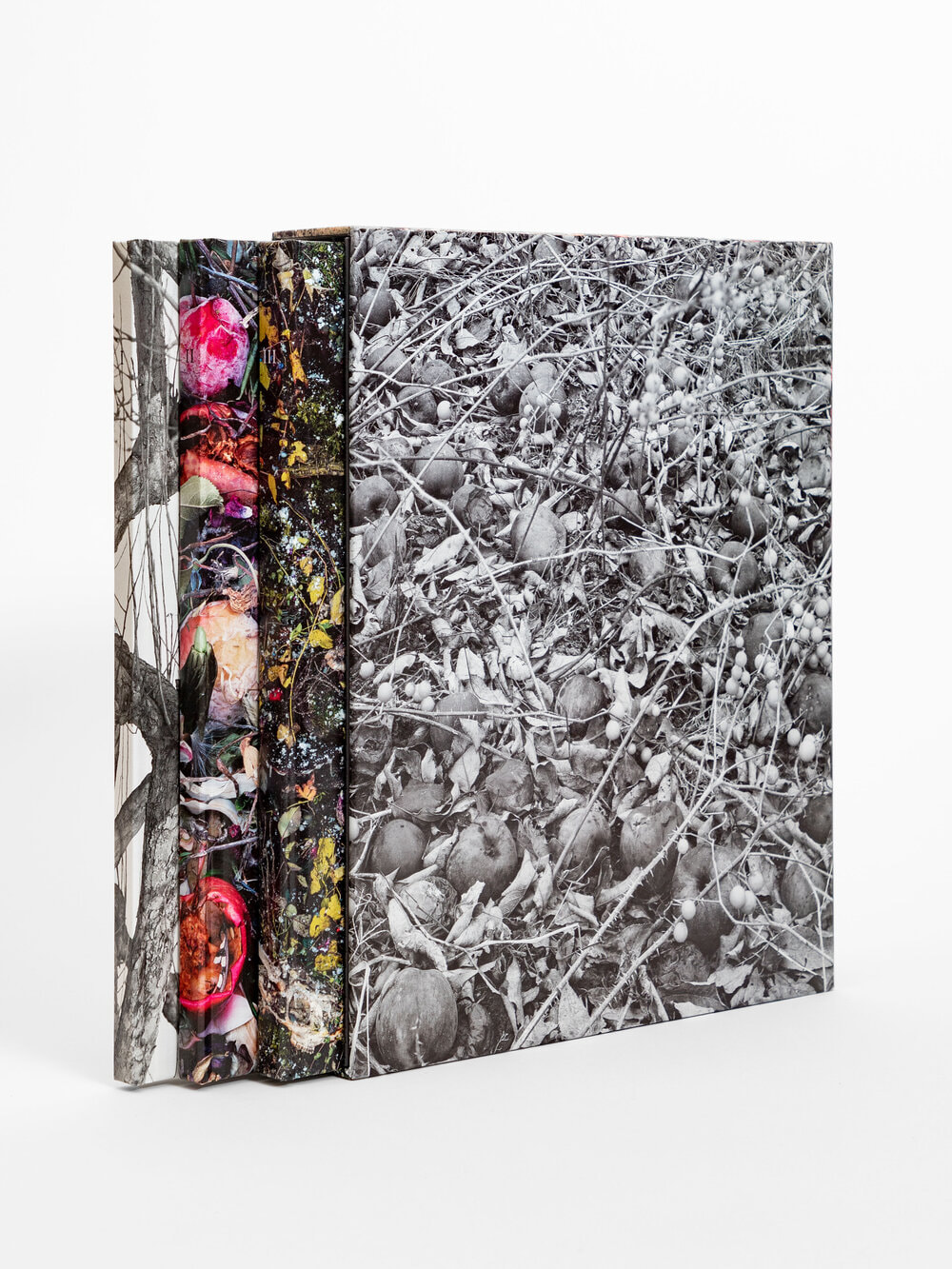

About the PhotographerTanya Marcuse began making photographs as an early college student at Bard College at Simon’s Rock. She went on to study Art History and Studio Art at Oberlin and earned her MFA from Yale. Her photographs are in many collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the George Eastman Museum. In 2002, she received a Guggenheim fellowship to pursue her project Undergarments and Armor. In 2005, she embarked on a three-part, fourteen year project, Fruitless | Fallen | Woven, moving from iconic, serial photographs of trees in Fruitless to lush, immersive, allegorical works in Fallen and Woven. The photographs in Woven are as large as 5 x 13 feet. Fueled by the Biblical narrative of the fall from Eden, these related projects use increasingly fantastical imagery and more elaborate methods of construction to explore cycles of growth and decay and the dynamic tension between the passage of time and the photographic medium. Marcuse is a student of martial arts and boxing as a method of cultivating mental and physical concentration and discipline. Tanya’s books include Undergarments and Armor (Nazraeli Press, 2005), Wax Bodies, (Nazraeli Press, 2012) and Fruitless | Fallen | Woven (Radius Press, 2019) and INK (Fall Line Press, 2021). She teaches Photography at Bard College. An exhibition at the International Center of Photography, Actual Size!, showing January 28 – May 02, 2022, includes a life-sized photograph from Marcuse's Woven series. |

|

Truth in Photography: Could you talk about your process for making photographs?

Tanya Marcuse: That’s a big question for me. My process varies from project to project, depending on my intentions. The process of creating the pieces in the Woven series developed over a year-long period of trial and error. The frustrations and obstacles were instrumental in identifying what I was and wasn’t after. It began with an intuition that I wanted to capture the viewer's peripheral vision and shift from the 4 x 5 aspect ratio I’d been working with for many years to a 1:2 ratio. To achieve this it seemed obvious enough to use an 8 x 10” view camera, (modifying my film holders to the 1: 2 ratio), but I soon discovered that things in the center of the frame looked fabulous while the sharpness and beauty of description diminished on the periphery– especially when printed huge. This changed my technical method as well as clarifying my intentions. I realized that I was after a spread out, even, description where a stick in the lower right corner would be described with the same intensity and respect as an object in the center of the frame.

Anyway, I developed a method of composing a kind of tableau –made up of things I’ve collected from the natural world --on a wooden frame I designed. The frame is kind of like a garden bed tilted up at a 45 degree angle. I see this as a canvas, a garden and a living and dying diorama. In fact, I often research diorama techniques. How to make fake snow, or a believable ground, or an illusion of water. Though my tableau only needs to last for the day of the shoot –it’s totally ephemeral. The composition process takes anywhere from two weeks to three months. Each piece begins with a spark of an idea or image that points me in a direction. The piece unfolds and changes. I make sketches, ingredient lists, notes on timing (the timing of one piece, Woven Nº 27, hinged on the monarch life cycle and wanting to use real chrysalids in the piece). But I never know where it’s going.

Tanya Marcuse: That’s a big question for me. My process varies from project to project, depending on my intentions. The process of creating the pieces in the Woven series developed over a year-long period of trial and error. The frustrations and obstacles were instrumental in identifying what I was and wasn’t after. It began with an intuition that I wanted to capture the viewer's peripheral vision and shift from the 4 x 5 aspect ratio I’d been working with for many years to a 1:2 ratio. To achieve this it seemed obvious enough to use an 8 x 10” view camera, (modifying my film holders to the 1: 2 ratio), but I soon discovered that things in the center of the frame looked fabulous while the sharpness and beauty of description diminished on the periphery– especially when printed huge. This changed my technical method as well as clarifying my intentions. I realized that I was after a spread out, even, description where a stick in the lower right corner would be described with the same intensity and respect as an object in the center of the frame.

Anyway, I developed a method of composing a kind of tableau –made up of things I’ve collected from the natural world --on a wooden frame I designed. The frame is kind of like a garden bed tilted up at a 45 degree angle. I see this as a canvas, a garden and a living and dying diorama. In fact, I often research diorama techniques. How to make fake snow, or a believable ground, or an illusion of water. Though my tableau only needs to last for the day of the shoot –it’s totally ephemeral. The composition process takes anywhere from two weeks to three months. Each piece begins with a spark of an idea or image that points me in a direction. The piece unfolds and changes. I make sketches, ingredient lists, notes on timing (the timing of one piece, Woven Nº 27, hinged on the monarch life cycle and wanting to use real chrysalids in the piece). But I never know where it’s going.

Woven: In Process video, no sound

All of this takes place in my backyard, under a huge canopy that becomes an evenly lit lightbox. I photograph the tableau from a scaffold, the camera back parallel to the scene on the wooden frame. I shoot digitally, taking many frames and stitching them together in post-production to create a super high resolution file. Such that when a viewer moves in close there is no disappointment, only reward.

Another key tool in my process is my freezer. Freezing plants, animals and fruit allows me to halt their growth or decay. Woven Nº 30 is a distinctly late fall scene, with a dusting of early snow. Yet burgundy shoots of juvenile skunk cabbage (that I collected in spring and froze) emerge from the ground. This method helps me to explore the plausible and the fantastical in the believable language of the photograph.

TiP: When you're making photographs, what are you trying to do? What's your goal? What do you look for?

Marcuse: In my recent projects giving the viewer an immersive sense of wonder is paramount. My goal is for the pieces to work as allover compositions from afar, but also as luscious still-lives when drawn in close. I want to invite a viewer into the world in the photograph where they can have their own passage between belief and doubt –a seduction side by side with skepticism about that relationship between the constructed and the natural. However fabled, the scene is still real and factual, presented across the picture plane –like a platter– to the viewer.

Another key tool in my process is my freezer. Freezing plants, animals and fruit allows me to halt their growth or decay. Woven Nº 30 is a distinctly late fall scene, with a dusting of early snow. Yet burgundy shoots of juvenile skunk cabbage (that I collected in spring and froze) emerge from the ground. This method helps me to explore the plausible and the fantastical in the believable language of the photograph.

TiP: When you're making photographs, what are you trying to do? What's your goal? What do you look for?

Marcuse: In my recent projects giving the viewer an immersive sense of wonder is paramount. My goal is for the pieces to work as allover compositions from afar, but also as luscious still-lives when drawn in close. I want to invite a viewer into the world in the photograph where they can have their own passage between belief and doubt –a seduction side by side with skepticism about that relationship between the constructed and the natural. However fabled, the scene is still real and factual, presented across the picture plane –like a platter– to the viewer.

TiP: Because the size of this frame that you use is relatively small, in effect, you're creating an illusion of it being more expansive.

Marcuse: Well, the size of the frame is the size of the photograph. The frame that I work on is 5x15 feet. For most of Woven, I stuck to a 1x2 aspect ratio, and most of the pieces are 5x10 feet. In Woven Nº 30 at the ICP, it's a bit larger –5 x 13 feet. It's the largest piece I've ever made. So it's certainly smaller than the world, right? But in a way, it's huge, right?

I also photograph out in the larger world off of my wooden structure, and then I'm working with the photographic frame in a different way. Stephen Shore talks about the way photography is subtractive —where there's this vast, vast world filled with infinite photographic possibilities. A photographer selects one frame from a very specific vantage point. When I’m out in the world, off of the wooden structure, I’m working subtractively. But when I’m composing on my wooden frame, I'm working additively, the way a painter might work. I'm starting with nothing but the bare frame and adding content: dirt, bark and rocks, living and dead things. Some things I can control. Some things get beyond my control. Ferns grow larger than I expect. Some things die. It becomes a kind of living and dying diorama, if you will. That's how I think about the frame and the connection between the method and the meaning. Method is deeply connected to meaning.

TiP: What kind of camera do you use?

Marcuse: In Woven I moved from the 4 x 5 view camera to working with a digital SLR. I use a Nikon D800 for the Woven pieces and a Fuji GFX 50s when I’m photographing out in the world. In Woven (as well as my new project Book of Miracles) I take 30 to 50 frames, depending on the scale of the piece, and stitch them together in post-production. I've moved from the monocular perspective of the view camera to a kind collection of views. The photographs in Woven are a kind of florilegium of slightly different perspectives. It’s no longer a single moment. I shoot all the frames in a session, but it's not a single 500th of a second decisive moment.

Marcuse: Well, the size of the frame is the size of the photograph. The frame that I work on is 5x15 feet. For most of Woven, I stuck to a 1x2 aspect ratio, and most of the pieces are 5x10 feet. In Woven Nº 30 at the ICP, it's a bit larger –5 x 13 feet. It's the largest piece I've ever made. So it's certainly smaller than the world, right? But in a way, it's huge, right?

I also photograph out in the larger world off of my wooden structure, and then I'm working with the photographic frame in a different way. Stephen Shore talks about the way photography is subtractive —where there's this vast, vast world filled with infinite photographic possibilities. A photographer selects one frame from a very specific vantage point. When I’m out in the world, off of the wooden structure, I’m working subtractively. But when I’m composing on my wooden frame, I'm working additively, the way a painter might work. I'm starting with nothing but the bare frame and adding content: dirt, bark and rocks, living and dead things. Some things I can control. Some things get beyond my control. Ferns grow larger than I expect. Some things die. It becomes a kind of living and dying diorama, if you will. That's how I think about the frame and the connection between the method and the meaning. Method is deeply connected to meaning.

TiP: What kind of camera do you use?

Marcuse: In Woven I moved from the 4 x 5 view camera to working with a digital SLR. I use a Nikon D800 for the Woven pieces and a Fuji GFX 50s when I’m photographing out in the world. In Woven (as well as my new project Book of Miracles) I take 30 to 50 frames, depending on the scale of the piece, and stitch them together in post-production. I've moved from the monocular perspective of the view camera to a kind collection of views. The photographs in Woven are a kind of florilegium of slightly different perspectives. It’s no longer a single moment. I shoot all the frames in a session, but it's not a single 500th of a second decisive moment.

TiP: In terms of your photographs, because you are constructing a reality, how do you describe seeing one of your images?

Marcuse: I would hope that it would be a magical encounter with something that you might find in the forest, but that you also never quite would. Like in a diorama, there is an implausible abundance of species in a condensed area. The image might resemble a fairy tale synthesized with what we call real life. In this scene (in Woven Nº 30), the ferns are still green, but winter is coming. There are little icicles forming on old mushrooms, on a deer carcass and skull. There's a dusting of snow on a pheasant, which has died. There's blue and purple berries and a palette of a greenish yellow, with little dots of blue porcelain berries and purple amethyst and some purple monkswood intermingled in the scene that help the viewer's eye to travel through the scene across the photograph.

Marcuse: I would hope that it would be a magical encounter with something that you might find in the forest, but that you also never quite would. Like in a diorama, there is an implausible abundance of species in a condensed area. The image might resemble a fairy tale synthesized with what we call real life. In this scene (in Woven Nº 30), the ferns are still green, but winter is coming. There are little icicles forming on old mushrooms, on a deer carcass and skull. There's a dusting of snow on a pheasant, which has died. There's blue and purple berries and a palette of a greenish yellow, with little dots of blue porcelain berries and purple amethyst and some purple monkswood intermingled in the scene that help the viewer's eye to travel through the scene across the photograph.

TiP: Could you complete the sentence, “Truth in photography is…”?

Marcuse: I would say truth in photography is a fiction. I don't really believe in truth in photography. Like the way in which the Enlightenment Truth with a capital T is problematic. It implies an omniscient singularity, I think truth in photography is similarly problematic. I think photography has a staggeringly rich and complex relationship to fact, to description, and to actuality. But the method of creating a photograph, and the zillions of different methods of making a photograph, make it so that I don’t think there is the possibility of any kind of capital T truth in photography. I think it's very important to say that I don't think that is new. It is not because of Photoshop, it is not because of constructed tableaux. Photography, to me, has always been a fiction.

When I began photographing as a 17-year-old in 1982, the medium took me by storm. It just completely transformed and possibly saved my life. I think the reason why it was and still is so powerful for me is because of this relationship between the internal world and the external world, and the possibility of those worlds meeting through the language of the photograph. I think of the photograph as a translation of the world, not unlike a translation from one language into another, where the best translations become something new. When the translator is willing to transform one language into the new one. Some of the original meaning will be lost and changed in order to create something new that's filled with the purpose and intention in the new language.

TiP: Talk about the importance of how scale affects perception.

Marcuse: I love the concept for this show, Actual Size!, that David Campany has formed, because it just raises so many questions about the relationship between photography and the world. I will start by just saying that the scale of the photographic object is something that has always been very important to me. For 15 years, I made intimate 4x5 inch photographs that pulled the viewer in close in a very particular kind of way. I certainly never would have thought that I would be working 5x13 feet. I would have built a different studio had I had any foreshadowing of that.

Marcuse: I would say truth in photography is a fiction. I don't really believe in truth in photography. Like the way in which the Enlightenment Truth with a capital T is problematic. It implies an omniscient singularity, I think truth in photography is similarly problematic. I think photography has a staggeringly rich and complex relationship to fact, to description, and to actuality. But the method of creating a photograph, and the zillions of different methods of making a photograph, make it so that I don’t think there is the possibility of any kind of capital T truth in photography. I think it's very important to say that I don't think that is new. It is not because of Photoshop, it is not because of constructed tableaux. Photography, to me, has always been a fiction.

When I began photographing as a 17-year-old in 1982, the medium took me by storm. It just completely transformed and possibly saved my life. I think the reason why it was and still is so powerful for me is because of this relationship between the internal world and the external world, and the possibility of those worlds meeting through the language of the photograph. I think of the photograph as a translation of the world, not unlike a translation from one language into another, where the best translations become something new. When the translator is willing to transform one language into the new one. Some of the original meaning will be lost and changed in order to create something new that's filled with the purpose and intention in the new language.

TiP: Talk about the importance of how scale affects perception.

Marcuse: I love the concept for this show, Actual Size!, that David Campany has formed, because it just raises so many questions about the relationship between photography and the world. I will start by just saying that the scale of the photographic object is something that has always been very important to me. For 15 years, I made intimate 4x5 inch photographs that pulled the viewer in close in a very particular kind of way. I certainly never would have thought that I would be working 5x13 feet. I would have built a different studio had I had any foreshadowing of that.

The dynamics of scale –both of the photograph itself, and the objects described within, allow me to play with perception. The relationship between the viewer and the object of the photograph is at the heart of my decisions about scale. In these large works the scale of the photographic objects outsizes the scale of the body. The objects featured within are at actual scale. It’s intriguing to me that this actual size description lends itself to the sensation of the hyper-real, rather than the ordinary. In earlier pieces from the Woven series the scale of the material used in the photographs tended to be smaller, a vast collection of intricate vines, berries, birds. But as the series evolved, working with larger objects –deer heads or a whole pheasant –was a new kind of challenge and very engaging.

I think it’s fascinating and a little funny that we refer to actual size in photography, because we're still translating the three-dimensional world into the two-dimensional one. So in a sense, there's no possibility of actual size in photography. It’s not a plaster cast.

TiP: Talk about the idea of photography as translation.

Marcuse: I would say that photography translates the three-dimensional infinite world into something new. It’s miraculous when this alchemical transformation is complete. In some photographs you can see arbitrary elements from the world hindering the translation. It’s not fully realized.

A surveillance camera is going to make that translation dramatically differently than Eugène Atget or Deana Lawson. That’s part of my reluctance to embrace any essential, pervasive qualities of the medium. There are so many photographies.

I think it’s fascinating and a little funny that we refer to actual size in photography, because we're still translating the three-dimensional world into the two-dimensional one. So in a sense, there's no possibility of actual size in photography. It’s not a plaster cast.

TiP: Talk about the idea of photography as translation.

Marcuse: I would say that photography translates the three-dimensional infinite world into something new. It’s miraculous when this alchemical transformation is complete. In some photographs you can see arbitrary elements from the world hindering the translation. It’s not fully realized.

A surveillance camera is going to make that translation dramatically differently than Eugène Atget or Deana Lawson. That’s part of my reluctance to embrace any essential, pervasive qualities of the medium. There are so many photographies.

TiP: How do your photographs translate what you're seeing?

Marcuse: It’s not just a question of what I’m seeing, but also a question of imagination. We have internal vision, not only external. Both Fallen and Woven are, at heart, allegorical. I’m imagining the garden of Eden after Adam and Eve have been expelled. I picture the untended garden of paradise as a place of both abundance and rot. There is no longer a singular serpent but many. Bats, mice, insects and other species, not native to paradise have entered the scene. Because of the transgression, the life cycles of growth and decay are exaggerated, and death is a major player.

TiP: Talk about the elements of translation. There’s framing, there’s color, there’s light and shadow.

Marcuse: It’s not just a question of what I’m seeing, but also a question of imagination. We have internal vision, not only external. Both Fallen and Woven are, at heart, allegorical. I’m imagining the garden of Eden after Adam and Eve have been expelled. I picture the untended garden of paradise as a place of both abundance and rot. There is no longer a singular serpent but many. Bats, mice, insects and other species, not native to paradise have entered the scene. Because of the transgression, the life cycles of growth and decay are exaggerated, and death is a major player.

TiP: Talk about the elements of translation. There’s framing, there’s color, there’s light and shadow.

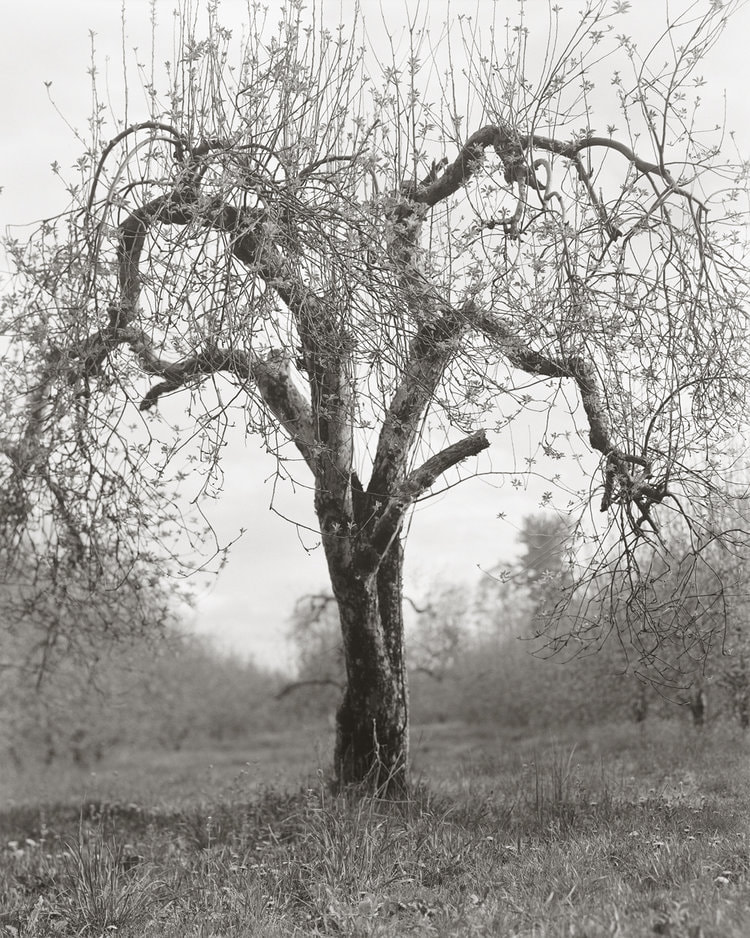

|

Marcuse: Following the language analogy, I would say I lean into different aspects of photographic syntax depending on the conceptual foundation of the project. The method that I'm using in Woven, is quite different from the images in Fruitless, where I'm photographing a singular tree out in an orchard with a view camera in black and white. The portrait-like singularity of individual trees is served by the 4 x 5 view with the lens at a shallow depth-of-field. That’s what I would describe as a different method of translating the world – where these syntactical decisions are an expression of the conceptual and visual underpinnings of a project.

My book Fruitless | Fallen | Woven (Radius Books) traces the arc of these shifts. |

TiP: What’s the importance of color?

Marcuse: I worked almost exclusively in black and white until 2006. I came to color a little like Dorothy (in The Wizard of Oz) opening the door of her fallen house and looking out onto Oz saying, “Toto, we're not in Kansas anymore.” You might think color would be more tied to actuality, but for me color is a kind of fable and also connects me more deeply to the history of painting. Mostly, I just have a love relationship with color, almost erotic. It's lusty and luscious, you know? It's very physical.

Marcuse: I worked almost exclusively in black and white until 2006. I came to color a little like Dorothy (in The Wizard of Oz) opening the door of her fallen house and looking out onto Oz saying, “Toto, we're not in Kansas anymore.” You might think color would be more tied to actuality, but for me color is a kind of fable and also connects me more deeply to the history of painting. Mostly, I just have a love relationship with color, almost erotic. It's lusty and luscious, you know? It's very physical.

TiP: What about light and shadow?

Marcuse: Light and shadow are what create an illusion of volume, an illusion of three-dimensions. They're part of the expressive and technical toolset that we have as photographers, whether found light or artificial light. The piece in the show is made underneath a big canopy, (that I mentioned before), which I use because it's like a big light box. So it can be bright and sunny out or it can be rainy, and the amount of light changes, but it's very, very even light. And there's a little bit of shadow –crucial for a sense of the gravity and physicality of the material, but not a lot of contrast, and it's extremely even. It fulfills my mission of creating a democracy of description across this frame that then becomes the photograph.

TiP: Talk about this idea of democracy of description. That's a wonderful phrase.

Marcuse: The Unicorn Tapestries have been an enormous influence, where the unicorn and figures have dominance over the millefleur background. There is a figure/ground hierarchy. On the other hand, there’s is a uniformity –or democracy– in the weaving of a tapestry, where a stitch on the lower right-hand corner is the same as a stitch in the center. A stitch is a great analogy for a pixel. I think of the photographs in Woven like Medieval tapestries without the central narrative, and the drama is spread out across the picture plane.

Marcuse: Light and shadow are what create an illusion of volume, an illusion of three-dimensions. They're part of the expressive and technical toolset that we have as photographers, whether found light or artificial light. The piece in the show is made underneath a big canopy, (that I mentioned before), which I use because it's like a big light box. So it can be bright and sunny out or it can be rainy, and the amount of light changes, but it's very, very even light. And there's a little bit of shadow –crucial for a sense of the gravity and physicality of the material, but not a lot of contrast, and it's extremely even. It fulfills my mission of creating a democracy of description across this frame that then becomes the photograph.

TiP: Talk about this idea of democracy of description. That's a wonderful phrase.

Marcuse: The Unicorn Tapestries have been an enormous influence, where the unicorn and figures have dominance over the millefleur background. There is a figure/ground hierarchy. On the other hand, there’s is a uniformity –or democracy– in the weaving of a tapestry, where a stitch on the lower right-hand corner is the same as a stitch in the center. A stitch is a great analogy for a pixel. I think of the photographs in Woven like Medieval tapestries without the central narrative, and the drama is spread out across the picture plane.

The size of Woven Nº 30 allowed me to use materials larger in scale than I would normally use—the deer skeleton, the pheasant. Situating these larger elements on the opposite ends of the frame and integrating them into the world in the photograph mitigates their dominance in the scene and is part of the democratic method of description that I love so much. So much comes from that impulse, the light comes from that, the composition comes from that. No one thing gets priority in terms of its allegorical significance or visual weight. It sounds cheesy, but I’m trying to convey the wonder –love even– that I feel towards the tiniest most ordinary thing one might find in the natural world (a gray stick, or plain leaf). The democracy of description brings the remarkable and the quotidian onto the same plane, and suggests that the quotidian is remarkable, and the remarkable is quotidian.

|

|

|